CHCS

Center for

Health Care Strategies, Inc.

Health Literacy

Implications of the

Affordable Care Act

Commissioned by:

The Institute of Medicine

Authored by:

Stephen A. Somers, PhD

Roopa Mahadevan, MA

Center for Health Care Strategies, Inc.

November 2010

Health Literacy Implications of the Affordable Care Act

© 2010 Center for Health Care Strategies, Inc.

S.A. Somers and R. Mahadevan. Health Literacy Implications of the Affordable Care Act. Center for Health Care Strategies, Inc.,

November 2010.

Contents

Acknowledgements ....................................................................................................................................... 3

I. Health Literacy and Health Care Reform ................................................................................................. 4

Health Literacy Until Now ...................................................................................................................... 5

II. Health Literacy and the Affordable Care Act ......................................................................................... 7

Definition ................................................................................................................................................. 7

Direct Mentions ....................................................................................................................................... 7

Indirect Provisions ................................................................................................................................... 9

Insurance Reform, Outreach, and Enrollment ................................................................................ 9

Individual Protections, Equity, and Special Populations .............................................................. 11

Workforce Development ............................................................................................................... 13

Health Information ........................................................................................................................ 14

Public Health, Health Promotion, and Prevention & Wellness ................................................... 16

Innovations in Quality and the Delivery and Costs of Care ......................................................... 18

Best Practices: “What Are My Medi-Cal Choices?” .............................................................................. 20

III. Conclusion ............................................................................................................................................ 21

IV. Appendices ........................................................................................................................................... 22

Appendix A: Summary of ACA Provisions with Potential Implications for Health Literacy ............. 22

Appendix B: Instances of “Culturally and Linguistically Appropriate” in the ACA .......................... 31

The Center for Health Care Strategies (CHCS) is a nonprofit health policy resource center dedicated to improving health

care quality for low-income children and adults, people with chronic illnesses and disabilities, frail elders, and racially and

ethnically diverse populations experiencing disparities in care. CHCS works with state and federal agencies, health plans,

providers and consumer groups to develop innovative programs that better serve Medicaid beneficiaries with complex and

high-cost health care needs. Its program priorities are: improving quality and reducing racial and ethnic disparities; integrating

care for people with complex and special needs; and building Medicaid leadership and capacity.

Health Literacy Implications of the Affordable Care Act

3

Acknowledgements

he authors thank Sara Rosenbaum, Hirsh Professor and Chair of Health Policy at George

Washington University, for her cogent analysis of the legislation and insights into the opportunities

it presents for promoting health literacy. We also wish to acknowledge the contributions of our

colleagues at Center for Health Care Strategies (CHCS), particularly Stacey Chazin, Michael Canonico,

Vincent Finlay, and Dorothy Lawrence, for their assistance in preparing this document.

CHCS expresses appreciation to the Institute of Medicine (IOM) for commissioning this report,

highlights of which the authors shared at the IOM Health Literacy Roundtable Workshop in

Washington D.C., on November 10, 2010.

T

Health Literacy Implications of the Affordable Care Act

4

I. Health Literacy and Health Care Reform

lthough low health literacy is certainly not a featured concern of the health care reform legislation

passed in early 2010, there are those who would argue that the law cannot be successful without a

redoubling of national efforts to address the issue. Nearly 36 percent of America’s adult population — 87

million adults — is considered functionally illiterate.

1

As the Patient Protection and Affordable Care

Act (ACA) extends health insurance coverage to some 32 million lower-income adults and promotes

greater attention to the barriers faced by individual patients, those implementing the law should consider

how to incorporate health literacy into strategies for enrolling beneficiaries and delivering care.

For the purposes of this paper, health literacy is defined, using the National Library of Medicine’s

definition, as:“The degree to which individuals have the capacity to obtain, process, and understand basic health

information and services needed to make appropriate health decisions.”

2

Fortunately, several ACA provisions directly acknowledge the need for greater attention to health

literacy, and many others imply it. The law includes provisions to communicate health and health care

information clearly; promote prevention; be patient-centered and create medical or health homes; assure

equity and cultural competence; and deliver high-quality care. This paper identifies both the direct and

indirect links, and provides those concerned about health literacy with provision-specific opportunities

to support advancements. These provisions fall into six health and health care domains in the legislation

where further action may be called for by concerned stakeholders:

(1) Coverage expansion: enrolling, reaching out to, and delivering care to health insurance coverage

expansion populations in 2014 and beyond;

(2) Equity: assuring equity in health and health care for all communities and populations;

(3) Workforce: training providers on cultural competency, language, and literacy issues

(4) Patient information at appropriate reading levels;

(5) Public health and wellness; and

(6) Quality improvement: innovation to create more effective and efficient models of care,

particularly for those with chronic illnesses requiring extensive self-management.

Individuals with low levels of health literacy are least equipped to benefit from the ACA, with

potentially costly consequences for both those who pay for and deliver their care, as well as for

themselves. Rates of low literacy are disproportionately high among lower-income Americans eligible for

publicly financed care through Medicare or Medicaid.

3

In 2014, this pattern is likely to extend to

individuals newly eligible for Medicaid or for publicly subsidized private insurance through state-based

exchanges.

1

J. Vernon, A. Trujillo, S. Rosenbaum, and B. DeBuono. Low Health Literacy: Implications for National Health Policy. University of

Connecticut, 2007.

2

S.C. Ratzan and R.M. Parker. Introduction. In: National Library of Medicine Current Bibliographies in Medicine: Health Literacy.

NLM Pub. No. CBM 2000-1 (2000).

3

M. Kutner et al. The Health Literacy of America’s Adults: Results from the 2003 National Assessment of Adult Literacy. U.S.

Department of Education, National Center for Education. Washington DC, 2006.

A

Health Literacy Implications of the Affordable Care Act

5

Health Literacy Until Now

In its Healthy People 2010 aims statement, the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS)

adopted the definition from the National Library of Medicine, declaring health literacy to be an

important national health priority. Healthy People 2010 broadened this definition to note that health

literacy is not just the problem of the individual, but also a by-product of system-level contributions.

4

Acknowledging the salience of this issue, HHS Secretary Kathleen Sebelius made official a federal

commitment to health literacy by releasing in May 2010 the National Action Plan to Improve Health

Literacy.

5

The plan lays out seven goals that emphasize the importance of creating health and safety

information that is accurate, accessible and actionable. It addresses payers, the media, government

agencies, health care professionals and others, recognizing the multi-sector effort that will be required to

effectively tackle this oft-ignored, national problem.

The U.S. health care system, with its myriad public and private programs, institutions, services, products,

and information, poses a significant challenge to those seeking access to affordable, quality health care.

Understanding the complexities of insurance eligibility, therapeutic guidance, medical technology,

prescription medication, disease management, prevention, and lifestyle modification are difficult for any

consumer, let alone one with compromised levels of literacy or numeracy (or quantitative literacy). An

individual seeking to participate successfully in the health system requires a constellation of skills —

reading, writing, basic mathematical calculations, speaking, listening, networking, and rhetoric — the

totality of which defines health literacy.

However, national data suggest that only 12 percent of adults have proficient health literacy.

6

While low

health literacy is found across all demographic groups, it disproportionately affects non-white racial and

ethnic groups; the elderly; individuals with lower socioeconomic status and education; people with

physical and mental disabilities; those with low English proficiency (LEP); and non-native speakers of

English.

7

Low health literacy is associated with reduced use of preventive services and management of

chronic conditions, and higher mortality.

8

It also leads to medication errors, misdiagnosis due to poor

communication between providers and patients, low rates of guidance and treatment compliance,

hospital readmissions, unnecessary emergency room visits, longer hospital stays, fragmented access to

care, and poor responsiveness to public health emergencies.

9

Accordingly, low health literacy has been

estimated to cost the U.S. economy between $106 billion and $236 billion annually.

10

The consequences of low health literacy have been recognized by federal agencies such as the Agency for

Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ), the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), the

Food and Drug Administration (FDA), the Office of the Surgeon General, and the National Institutes of

Health (NIH), as well as by private organizations such as America’s Health Insurance Plans, the

American College of Physicians, the American Medical Association, The Joint Commission on

Accreditation, Kaiser Permanente, and Pfizer. These entities and many others are promoting awareness,

creating program initiatives, funding targeted research, setting readability standards, working with e-

health and social media platforms, and providing tools and resources for measurement and quality

4

R. Rudd. Objective 11-2. Improvement of Health Literacy. In: Communicating Health: Priorities and Strategies for Progress.

Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Washington DC, 2003.

5

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. National Action Plan to

Improve Health Literacy. Washington DC, 2010.

6

National Center for Education Statistics, U.S. Department of Education. “2003 National Assessment of Adult Literacy (NAAL).”

Available at http://nces.ed.gov/naal/.

7

L. Neilsen-Bohlman, A.M. Panzer, and D.A. Kindig. Health Literacy: A Prescription to End Confusion. National Academies Press.

Washington DC, 2004.

8

N.D. Berkman, et al. Literacy and Health Outcomes. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ). Rockville, MD, 2004.

9

Neilsen-Bohlman et al, op cit; Berkman et al, op cit., Vernon et al, op cit.

10

Vernon, et al., op cit.

Health Literacy Implications of the Affordable Care Act

6

improvement across providers, health plans, hospitals, and employer organizations. Important policy

papers such as the Institute of Medicine’s (IOM) 2004 report, Health Literacy: A Prescription to End

Confusion,

11

and national data such as those produced by the National Adult Literacy Survey

12

have

contributed to the knowledge base for this issue.

To date, however, strong legislative language, regulations, and appropriations for concerted efforts to

address health literacy have not emerged from the federal government. Congressional bills such as the

National Health Literacy Act of 2007

13

and the Plain Language Act of 2009,

14

which mapped out

meaningful health literacy strategies, have not yet made it to the President’s desk. It remains to be seen

whether the ACA can be used to push the national health literacy agenda forward.

11

Neilsen-Bohlman, et al., op cit.

12

National Center for Education Statistics, op cit.

13

U.S. Congress. “S. 2424: National Health Literacy Act of 2007.” 110

th

Congress. 2007 – 2008. Available at: http://www.

govtrack.us/congress/bill.xpd?bill=s110-2424.

14

U.S. Congress. “H.R. 946: Plain Writing Act of 2010.” 111

th

Congress 2009 – 2010. Available at: http://www.govtrack.us/

congress/bill.xpd?bill=h111-946. Note: The Plain Language Act of 2009 was mooted by passage of a related bill, the Plain

Writing Act of 2010, which was signed into law by President Obama on October 13, 2010, following completion of this paper.

Health Literacy Implications of the Affordable Care Act

7

II. Health Literacy and the Affordable Care Act

he ACA is, by any measure, a major piece of domestic policy legislation, directly affecting tens of

millions of Americans at a cost of nearly one trillion dollars over the next 10 years. The law’s

primary goals are to increase access to coverage, regulate the private insurance industry to allow more

Americans into the system at affordable rates, and begin to control the rate of growth in health care

costs. These goals cannot be achieved, however, without efforts to address cultural, linguistic and social

barriers to care facing vulnerable populations. Low health literacy is critical among these barriers. The

following ACA provisions include direct and indirect language concerning health literacy:

Definition

Title V, Subtitle A (amending existing laws and creating new law related to the health care workforce)

of ACA establishes a statutory definition of “health literacy” consistent with Healthy People 2010. The

term is defined as “the degree to which an individual has the capacity to obtain, communicate, process,

and understand health information and services in order to make appropriate health decisions.” Other

direct mentions of health literacy do not specifically cross-reference the Title V definition (though

presumably, HHS will use this terminology when implementing the various titles of the law).

Direct Mentions

Table 1 contains the law’s four other direct mentions of the term health literacy, These provisions touch

on issues of research dissemination, shared decision-making, medication labeling, and workforce

development. All four suggest the need to communicate effectively with consumers, patients, and

communities in order to improve the access to and quality of health care. None of these provisions

creates explicit health literacy programs, specifies implementation or regulatory supports, or expounds

further on the term “health literacy” beyond its mention. However, they are all consistent with the

themes of patient-centeredness and overall quality improvement that are found more broadly throughout

the legislation.

T

Health Literacy Implications of the Affordable Care Act

8

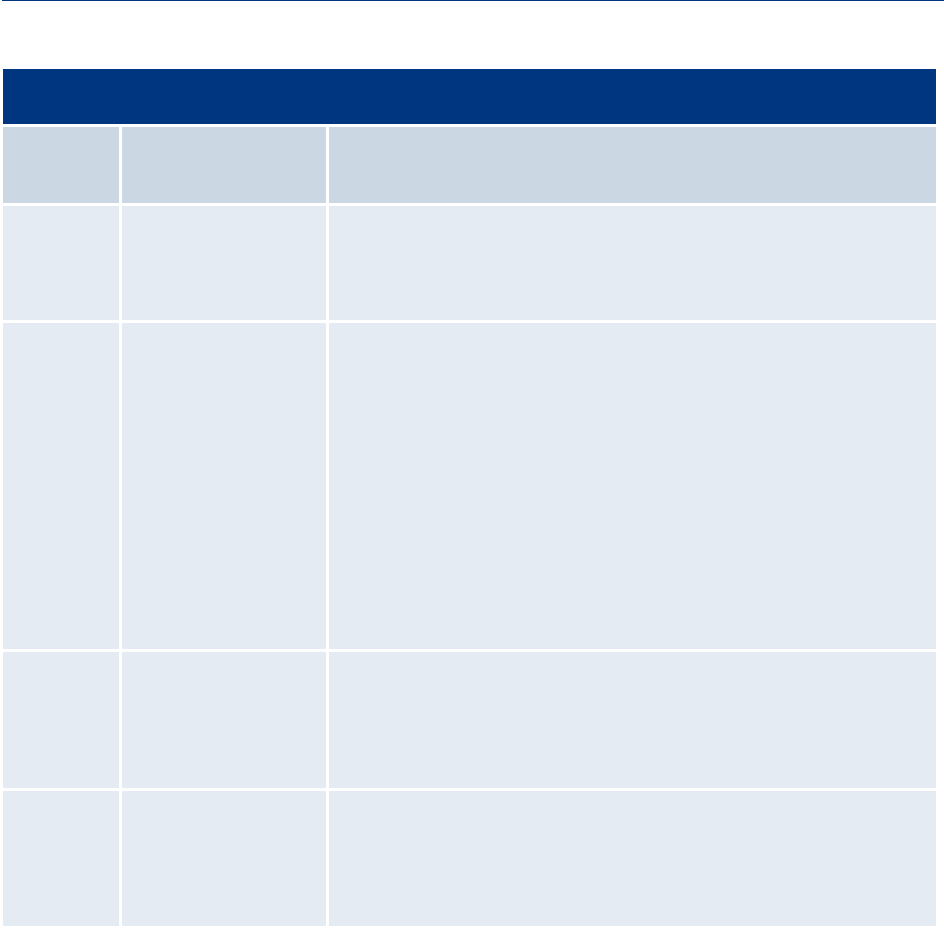

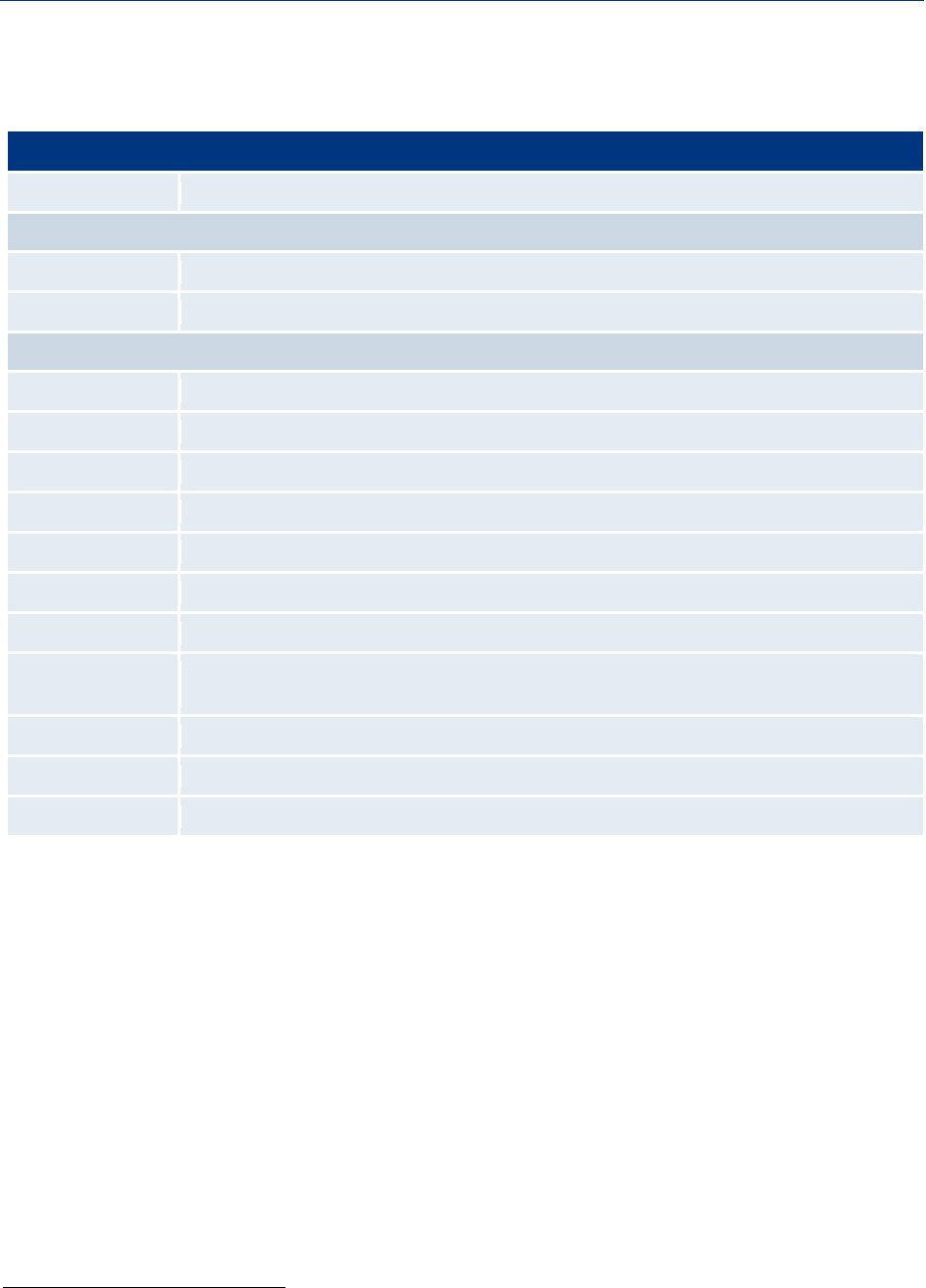

TABLE 1: ACA Provisions with Direct References to “Health Literacy”

Section

Number

Provision Title Legislative Language

Sec. 3501 Health Care Delivery

System Research;

Quality Improvement

Technical Assistance

Requires that research of the AHRQ’s Center for Quality Improvement and

Patient Safety be made “available to the public through multiple media and

appropriate formats to reflect the varying needs of health care providers and

consumers and diverse levels of health literacy.”

Sec. 3506 Program to Facilitate

Shared Decision-

making

Amends the Public Health Service Act to “facilitate collaborative processes

between patients, caregivers, authorized representatives and clinicians that

enables decision-making, provides information about tradeoffs among

treatment options, and facilitates the incorporation of patient preferences and

values into the medical plan.”

Authorizes a “program to update patient decision aids to assist health care

providers and patients.” The program, administered by the CDC and NIH,

awards grants and contracts to develop, update, and produce patient decision

aids for preference-sensitive care to assist providers in educating patients,

caregivers, and authorized representatives concerning the relative safety,

effectiveness and cost of treatment, or where appropriate, palliative care.

“Decision aids must reflect varying needs of consumers and diverse levels of

health literacy.”

Sec. 3507 Presentation of

Prescription Drug

Benefit and Risk

Information

Directs the Secretary to determine whether the addition of certain standardized

information to prescription drug labeling and print advertising would improve

health care decision-making by clinicians and patients and consumers; to

consider scientific evidence on decision-making; and to consult with various

stakeholders and “experts in health literacy.”

Sec. 5301

Training in Family

Medicine, General

Internal Medicine,

General Pediatrics, and

Physician Assistantship

Amends Title VII of the Public Health Service Act to permit the Secretary to

make training grants in the primary care medical specialties. Preference for

awards are for qualified applicants that “provide training in enhanced

communication with patients. . . and in cultural competence and health

literacy.”

Health Literacy Implications of the Affordable Care Act

9

Indirect Provisions

Other instances where the concept of health literacy could come into play include those discussed in the

following sections, organized into the six domains introduced at the outset. See the appendices for an

extensive list and descriptions of these and other provisions.

Insurance Reform, Outreach, and Enrollment

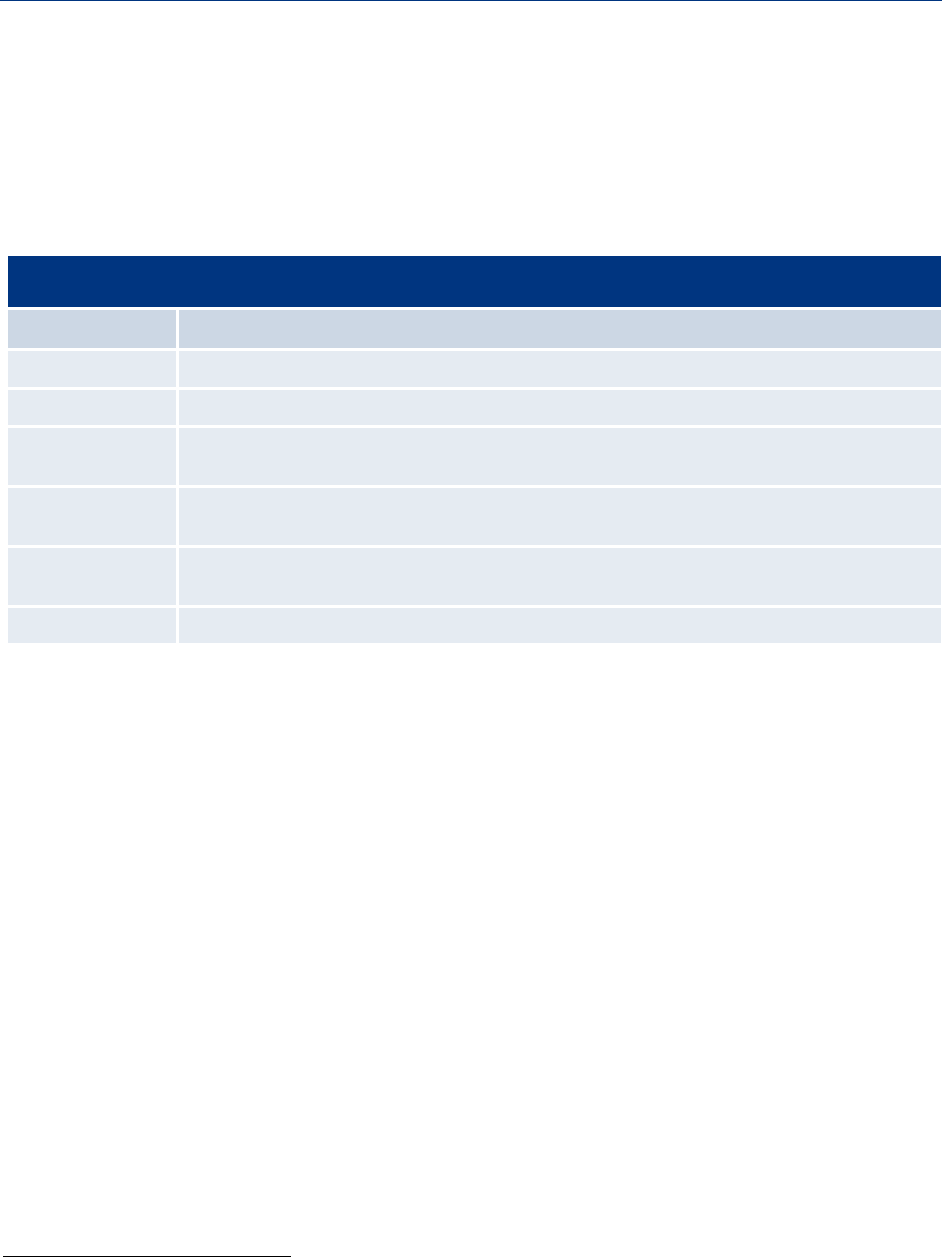

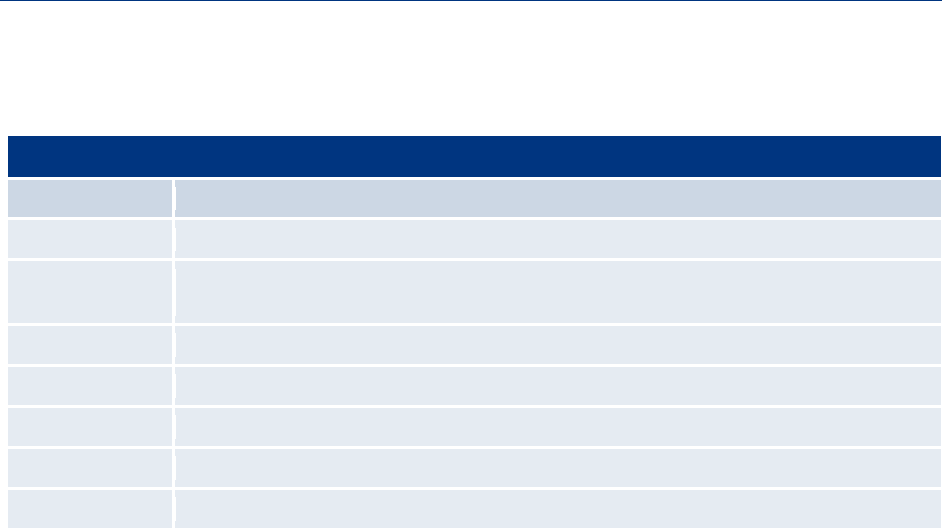

TABLE 2: Provisions Related to Insurance Reform, Outreach, and Enrollment

Section Number Provision Title

Sec. 1002 Health insurance consumer informatio

n

Sec. 1103 Immediate information that allows consumers to identify affordable coverage options

Sec. 1311 Affordable choices of health benefit plans

(includes language on “culturally and linguistically appropriate” obligations for plans)

Sec. 1413 Streamlining of procedures for enrollment through an Exchange and State Medicaid, CHIP, and

health subsidy programs

Sec. 2715 Development and utilization of uniform explanation of coverage documents and standardized

definitions.

Sec. 3306 Funding outreach and assistance for low-income programs.

Health insurance market reforms have substantial potential for reducing inequities in the health system

that are interrelated with insurance status. For example, the National Assessment of Adult Literacy

found that adults with no insurance are more likely to have “basic” or “below basic” health literacy than

“intermediate” or “proficient” health literacy.

15

A literature review prepared for the Kaiser Family

Foundation revealed that health insurance is the single-most significant factor explaining racial

disparities in having a usual source of care.

16,17

Broadly speaking, the ACA intends to improve access to health insurance in four main ways: (1) the

individual mandate, which requires all persons to have “qualifying or acceptable coverage”; (2) employer

mandates requiring coverage for employees in businesses with more than 50 employees; (3) regional/state

exchanges that allow individuals and small businesses to purchase coverage of varying benefit and cost,

and choose from subsidized plans (for those up to the 400 percent of the federal poverty level, or FPL);

and 4) the expansion of Medicaid eligibility to all individuals up to 133 percent of FPL. Additional

provisions seek to broaden the scope and affordability of insurance coverage by, among other things:

prohibiting insurance companies from rescinding coverage; extending dependent coverage for young

adults until age 26; eliminating lifetime limits on coverage; regulating annual dollar limits on insurance

coverage; and prohibiting the denial of coverage to children based on pre-existing conditions.

As many of those charged with implementing the ACA realize, none of these reforms will fully succeed

without efforts to make all of these opportunities understandable to the intended beneficiaries. These

expansions must be accompanied by targeted efforts to enroll under-resourced populations. Given their

15

National Center for Education Statistics, op cit.

16

Testimony of M. Lillie-Blanton, Dr.P.H., Senior Advisor on Race, Ethnicity, and Health Care, Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation,

before the House Ways and Means Subcommittee on Health. June 10, 2008.

17

American College of Physicians. Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care, Updated 2010. Philadelphia: American College of

Physicians, 2010.

Health Literacy Implications of the Affordable Care Act

10

inexperience with health coverage and the delivery system, these individuals will have greater difficulty

with a number of its facets: understanding eligibility guidelines for various insurance programs;

participating in the buy-in process of the exchange or high-risk pools; providing supplemental

identification and citizenship documentation necessary for enrollment; understanding which services are

covered; recognizing cost-sharing and premium responsibilities; and choosing a health care provider. All

of these tasks require significant consumer education and assistance. Notably, one ACA provision calls

for the development and utilization of uniform explanations of coverage documents and standardized

definitions. This is an important mandate that could be strengthened with explicit linkages to health

literacy.

The ACA also establishes an internet portal to help individuals and businesses interact with the

insurance exchange. This tool will have to assist users in understanding eligibility guidelines for

Medicaid/CHIP/Medicare/high-risk pools and subsidized private insurance. As such, the portal should

contain easy-to-understand explanations in simple English, as well as be available in multiple languages.

The ACA also requires that information presented by the national and regional exchanges be culturally

and linguistically appropriate.

To be most effective, ACA requirements to make insurance and enrollment information consumer-

friendly should extend beyond readable web and print materials to include media such as phone,

television, radio, social media, and in-person outreach. Research shows that a higher percentage of adults

with low literacy receive their information about health issues from radio and television than through

written sources, the internet, or social contacts.

18

Use of community-based organizations, culturally

specific media campaigns, promotores, and individual insurance brokers (many of whom will be displaced

due to the exchanges) will drive effective enrollment of the highly diverse, newly eligible population.

The economic recession has shown, for example, that affected families have turned first to community-

based organizations for help with linking them to public assistance programs.

19

States can use specially

allocated ACA funding for such local outreach and enrollment supports.

Medicaid Expansion. ACA law mandates that starting in 2014, Medicaid cover everyone under age 65

and 133 percent of FPL ($14,404 for one person in 2009). Accordingly, Medicaid could be serving

upwards of 80 million Americans — or a quarter of the U.S. population — each year after 2014. Recent

analyses suggest that this “expansion population” will likely: be racially and ethnically diverse; be

predominantly childless adults; have high levels of substance abuse and prior jail involvement; and

require integrated care management for complex physical and behavioral health needs.

20

It is fair to

assume that health literacy would be a significant issue for this population, as current Medicaid

beneficiaries face serious communication barriers related to limited literacy, language, culture, and

disability.

21

Most new enrollees are unlikely to have had prior insurance, and thus will have limited

knowledge about the Medicaid program, its services, and the complex administrative processes associated

with enrollment and participation.

Simplifying Medicaid enrollment for diverse populations is not a new concept: the majority of states

have some health literacy standards for their Medicaid programs. About 90 percent of all states have

18

M. Kutner, et al. The Health Literacy of America’s Adults: Results from the 2003 National Assessment of Adult Literacy.

Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education, 2006.

19

Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured. Optimizing Medicaid Enrollment: Perspectives on Strengthening Medicaid’s

Reach under Health Care Reform. Kaiser Family Foundation, Publication #8068, April 2010.

20

S. A. Somers, A. Hamblin, J. Verdier and V. Byrd. Covering Low-Income Childless Adults in Medicaid: Experiences from Selected

States. Center for Health Care Strategies. August 2010.

21

L. Neuhauser B. Rothschild, C. Graham, S.L. Ivey and S. Konishi. “Participatory Design of Mass Health Communication in Three

Languages for Seniors and People with Disabilities on Medicaid.” American Journal of Public Health (2009), 99(12): 2188-2195.

Health Literacy Implications of the Affordable Care Act

11

specific readability guidelines for Medicaid enrollment materials.

22

Of these, 67 percent call for at least a

sixth-grade reading level or a range including, and 22 percent call for the level to be even lower. Ninety-

six percent of states have simplified their enrollment forms, using easy-to-read language and repetition of

key messages, such as when to use emergency care services. Eighty-two percent of states offer one-on-one

enrollment assistance, and 72 percent provide onsite assistance at state agency offices, counseling

sessions at local nonprofits and community centers, and/or a toll-free helpline.

23

Despite these efforts,

many racial and ethnic minorities eligible for Medicaid or CHIP coverage — more than 80 percent of

eligible uninsured African-American children and 70 percent of eligible uninsured Latino children —

are still not enrolled.

24

For current Medicaid beneficiaries who do not speak English or who have LEP, most states provide

interpretive and translation services. The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) has

released readability guidelines for Medicaid print materials to states and has mandated certain contract

requirements around communication standards for Medicaid managed care plans.

25

However, these

guidelines lack strong enforcement or uniform oversight from any particular federal or state agency.

The following three ACA provisions, while not clearly linked to literacy, help further to simplify

Medicaid eligibility determinations and streamline enrollment: (1) elimination of the asset test that

many states still apply when determining Medicaid eligibility for adults, removing a common

administrative burden and impediment to participation; (2) usage of a new, uniform method for

determining income eligibility for most individuals (modified adjusted gross income, or MAGI); and (3)

the expansion of the state option to presumptive eligibility determinations. The ACA also streamlines

citizenship documentation requirements and electronic enrollment processes set forth by the Children’s

Health Insurance Program Reauthorization (CHIPRA) legislation in 2009.

26

To the extent that federal

entities could provide monetary and technical assistance support for state health literacy efforts,

Medicaid programs would be better able to effectively enroll and provide quality care to newly eligible,

low-literacy populations in 2014 and beyond.

Individual Protections, Equity, and Special Populations

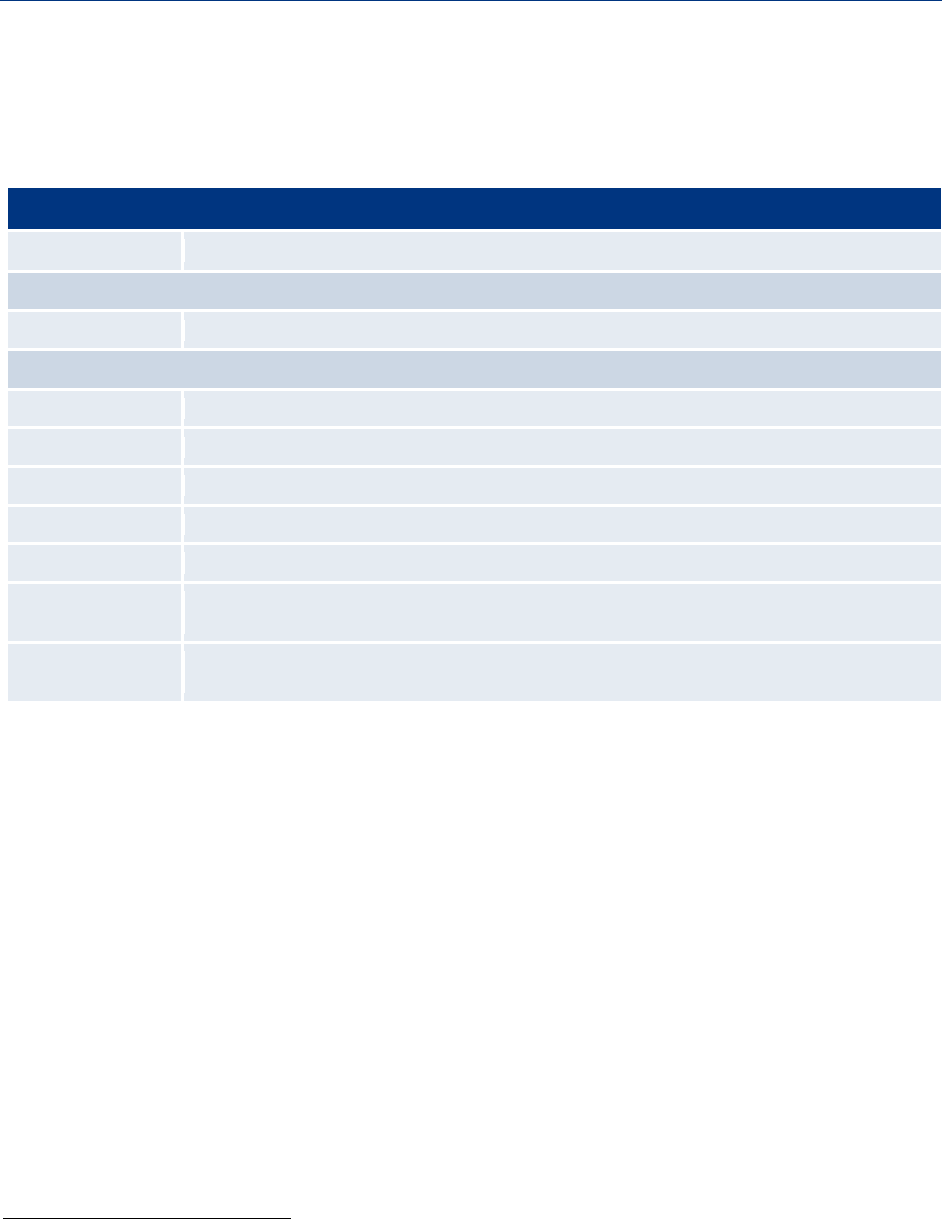

TABLE 3: Provisions Related to Individual Protections, Equity, and Special Populations

Sample of Indirect Instances where Health Literacy could be addressed

Section Number Provision Title

Sec. 1557. Nondiscrimination

Sec. 4302. Understanding health disparities; data collection and analysis

Sec. 6301. Patient-centered outcomes research

Sec. 10334. Minority health

The Insurance expansions in the ACA constitute significant steps toward universal coverage. All

Americans up to a certain level of poverty (133 percent) will for the first time be entitled to health

22

Health Literacy Innovations, LLC. National Survey of Medicaid Guidelines for Health Literacy. 2003.

23

T. Matthews and J. Sewell. State Official's Guide to Health Literacy. Lexington, KY: Council of State Governments, 2002.

24

American College of Physicians, op cit.

25

Rosenbaum et al. The Legality of Collecting and Disclosing Patient Race and Ethnicity Data. George Washington University

Department of Health Policy, 2006.

26

U.S. Congress. “H.R. 2: Children’s Health Insurance Program Reauthorization Act of 2009.” Available at: http://www.

govtrack.us/congress/bill.xpd?bill=h111-2.

Health Literacy Implications of the Affordable Care Act

12

insurance. Protecting these lower-income individuals’ right to health care is important to the successful

implementation of the ACA. The law references the Civil Rights Act, the Education Amendments Act,

the Age Discrimination Act, and the Rehabilitation Act. Section 1557’s Non-Discrimination provision

prevents exclusion of an individual from participation in or denial of benefits under any health program

or activity.

The ACA also provides consumers with significant new protections, including the ability to choose a

health plan that best suits their needs, to appeal a plan’s denial of coverage for needed services, and to

select an available primary care provider of their choosing. Health plans are now required to

communicate these patient protections in media that are “culturally and linguistically appropriate,” and

by extension, readable for those with low literacy levels. This term is used seven times in the legislation,

including in references to: federal oral health and nutrition education programs; clinical depression

centers of excellence; workforce training curricula; and the need for patient-centered delivery models to

be culturally competent, i.e. sensitive to the beliefs, values, and cultural mores that influence how health

care information is shared and received by individuals. Prior efforts of the HHS’ Office of Civil Rights to

set compliance standards for language aimed to improve access for those who have LEP and are already

providing related regulations. But, there is no language in the ACA instructing this body or others to

oversee the new “culturally and linguistically appropriate” obligations.

ACA law also requires the collection and reporting of data on race, ethnicity, sex, primary language, and

disability status by all federally conducted and supported health care and public health programs (e.g.,

Medicare, Medicaid), activities, and surveys (including surveys conducted by the Bureau of Labor

Statistics and the Bureau of the Census). It also urges the HHS to strengthen existing requirements that

state Medicaid agencies collect race, ethnicity, and language data. The law specifies that existing Office

of Management and Budget standards must be used, at a minimum, for recording race and ethnicity, and

instructs the HHS to issue new standards for measuring sex, primary language, and disability status.

In 2000, the Office of Minority Health (OMH) developed National Standards on Culturally and

Linguistically Appropriate Services (CLAS) to provide a common understanding and consistent

definitions of culturally and linguistically appropriate services in health care. These standards were

intended to be a practical framework for providers, payers, accreditation organizations, policymakers,

health administrators, and educators. Post-reform health literacy efforts should make use of this resource,

particularly since the OMH is gaining additional recognition in the law. The ACA establishes an OMH

in every major agency within the HHS: AHRQ, CDC, CMS, FDA, Health Resources and Services

Administration (HRSA), and Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration

(SAMHSA). These offices will be charged with evaluating the effectiveness of federal programs and

targeted research to meet the needs of minority populations. Similarly, a newly created Patient Centered

Outcomes Research Institute is tasked with conducting comparative effectiveness research, and ensuring

that subpopulations, particularly communities of color, are represented in research designs.

The ACA’s disparities agenda includes additional measures to support the rights and unique needs of

certain populations. These include standardizing complaint forms for patients in nursing facilities;

improving quality of care and protections for those in long-term care institutions; expanding aging and

disability resource centers; providing dementia prevention and abuse training for personnel working in

geriatric mental health; supporting pregnant and parenting teens and women through health care, social,

and educational assistance; and appropriating funds for the Indian Health Care Improvement Act,

27

which supports the growth of the Native American health care force and innovative delivery models for

27

U.S. Congress. “S.1790: Indian Health Care Improvement Reauthorization and Extension Act of 2009.” Dorgan, B. Available at:

http://www.govtrack.us/congress/bill.xpd?bill=s111-1790.

Health Literacy Implications of the Affordable Care Act

13

rural populations and tribal organizations. Again, however, these provisions make no explicit link to

health literacy.

Workforce Development

TABLE 4: Provisions Related to Workforce Development

Section Number Provision Title

Direct Mentions of Health Literacy

Sec. 5301 Training in family medicine, general internal medicine, general pediatrics, and physician assistantship

Sample of Indirect Instances where Health Literacy could be addressed

Sec. 5205 Allied health workforce recruitment and retention program

Sec. 5307 Cultural competency, prevention, and public health and individuals with disabilities training

Sec. 5313 Grants to promote the community health workforce

Sec. 5402 Health professions training for diversity

Sec. 5403 Interdisciplinary, community-based linkages

Sec. 5507

Demonstration project to address health professions workforce needs; extension of family-to-family

health information centers

Sec. 5606 State grants to health care providers who provide services to a high percentage of medically

underserved populations or other special populations

Within the next 40 years, people of color will make up the majority of the U.S. population.

28

Insurance

reforms and expansion of coverage will bring to providers’ offices new socially, culturally, and

linguistically diverse patient populations, many of which are likely to have limited experience with the

health system, difficulty communicating with practitioners, and complex conditions that require

effective self-management. There will be increased onus on health care providers and their delivery

system partners to be sensitive to the nuanced needs and potential limitations of their patient

populations. Not doing so could have major consequences for the patient’s health, the physician’s

performance, and the payer’s pocketbook.

Effectively communicating with low-literate patients is not an arcane skill: a survey of Federally

Qualified Health Centers, free clinics, and migrant health facilities found that when clinicians use plain

language, illustrations, and “talk back” methods, patient understanding, compliance, and trust are greatly

improved.

29

As it stands today, however, physicians are given little training in this area during the course

of their medical education,

30

and professionals who do receive a modicum of training in this vein —

community health workers and nurses, case managers, and public health specialists, for example — lack

recognition, funding, and inclusion in most physician-led delivery teams. Other system issues such as

pressure on provider time, use of singular modes of communication, and cultural mismatch between

provider and patient also contribute to subpar delivery of health care services to low-literate patients.

31

28

U.S. Census Bureau. “Projected Population of the United States, by Race and Hispanic Origin: 2000 to 2050.” Available at:

http://www.census.gov/ipc/www/usinterimproj/natprojtab01a.pdf.

29

Barrett S.E et al. Health Literacy Practices in Primary Care Settings: Examples from the Field. The Commonwealth Fund, 2008.

30

American College of Physicians. Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care, Updated 2010. Philadelphia: American College of

Physicians, 2010.

31

M.K. Paasche-Orlow, D. Schillinger, S.M. Green, and E.H. Wagner. “How Healthcare Systems can Begin to Address the

challenge of Limited Literacy. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 21(8): 884–887 (2006).

Health Literacy Implications of the Affordable Care Act

14

Appropriately, the ACA legislation pushes for improvement in the education and communications skills

of a wide range of health provider types, positioning workforce development as an important lever for

establishing health care equity across diverse patient populations.

The ACA provides scholarships, grants, and loan repayment programs for health care professionals in

medical fields such as primary care and mental health; offers continuing education support for those who

serve minority, rural, and special populations; and improves medical school and health professions

curricula in the areas of cultural competency and disabilities training. The ACA also seeks to increase

the racial/ethnic diversity of health practitioners through educational grants and loan programs, and

widens the array of professional and para-professionals available to patients through funding for training

of community health workers, nurses, geriatric specialists, adolescent mental health providers, home care

aides, and others.

Only one of these provisions — the primary care provider workforce training awards — explicitly

mentions the term health literacy. But, other language related to cultural and linguistic appropriateness

appears frequently, particularly as a condition of eligibility for the workforce grant opportunities.

Health Information

TABLE 5: Provisions Related to Health Information

Section Number Provision Title

Direct Mentions of Health Literacy

Sec. 3507 Presentation of prescription drug benefit and risk information

Sample of Indirect Instances where Health Literacy could be addressed

Sec. 3305 Improved information for subsidy eligible individuals reassigned to prescription drug and

MA-PD Plans

Sec. 3503 Grants to implement medication management services in treatment of chronic disease

Sec. 4205

N

utrition labeling of standard menu items at chain restaurants

Sec. 10328 Improvement in Part D medication therapy management (MTM) programs

While the average piece of health care information is written at a 10th-grade reading level, the average

American reads at only a fifth-grade level.

32

Numerous studies show that those with limited health

literacy skills are at increased risk of misunderstanding medical information on product labels, manuals,

package inserts, and nutrition labels.

33

,

34

The ACA provisions on nutrition labeling, the presentation of prescription drug information, and

medical management assistance are welcome. These provisions do not mandate health system-wide

standards but recommend small-scale changes and building an evidence base for future implementation.

They constitute an important step in acknowledging that health information, which is often dense,

technical, and jargon-filled, must be digestible to the diverse consumers who are trying to use it.

32

Rosales. “Are Adequate Steps Being Taken to Address Health Literacy in this Country?” Managed Care Outlook, 23(11), June 1,

2010.

33

Institute of Medicine. Preventing Medication Errors: The Quality Chasm Series. National Academies Press, 2006.

34

B.D. Weiss, M.Z. Mays, et al, “Quick Assessment of Literacy in Primary Care: The Newest Vital Sign.” Annals of Family Medicine

(2005), 3:514-522.

Health Literacy Implications of the Affordable Care Act

15

For example, due to the high national prevalence of cardio-metabolic conditions, consumers have a

greater need to read and interpret labels that provide information on sugar, fat, salt, and cholesterol

content. Difficulties in understanding nutrition information are heightened for those with “basic” and

“below basic” levels of literacy.

35

These individuals have trouble finding pieces of information or numbers

in a lengthy text, integrating multiple pieces of information in a document, or finding two or more

numbers in a chart and performing a calculation.

36

Elders and others with multiple chronic conditions are often given prescriptions for numerous

medications by a mix of physical health and mental health providers, who may not communicate with

each other about their prescription practices. This places the onus of medication reconciliation on the

patient, whose literacy and numeracy skills might be compromised.

Complications around choice of plan eligibility and prescription drug reimbursement add other

challenges for Part D Medicare beneficiaries. ACA provisions call for improved information for subsidy-

eligible individuals reassigned to prescription drug and MA-PD plans, and put into place medication

management programs for Part D seniors and chronic disease patients. These should help vulnerable

beneficiaries with their health information demands. To be effective, these efforts should also focus on

the verbal communications used by providers, pharmacists, and other dispensers of medication, to ensure

that patients understand medication dosage, schedules, side effects and safety precautions.

Given the increasing presence of information technology in health communications, delivery and

management, it will be important that this medium be accessible to low-literate, and low computer-

literate users in particular. In several instances, the ACA promotes the use of the internet and web-based

tools to disseminate health information and to communicate federal activities to a diverse consumer

population. Some of these include:

The “ombudsman” portal to facilitate enrollment into public and publicly subsidized insurance

programs and the exchange;

A website recommending prevention practices for specified chronic diseases and conditions;

A web-based tool to create personalized prevention plans; and

An internet portal for consumers to access health risk assessment tools.

Those designing these media should look to resources like the Health Literacy Online Guide,

37

a research-

based how-to module developed by the HHS’ Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion

(ODPHP) to guide administrators, providers, and educators seeking to present information to low-

literacy Americans using the web.

In terms of promoting the meaningful use of electronic health records (EHRs), there is little in the ACA

that speaks to health literacy. However, health literacy advocates might note relevant requirements in

the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (ARRA)

38

legislation: (1) patients must be provided

timely access (within 96 hours) to their electronic health information; (2) the EHR should be used to

35

The Joint Commission. What did the Doctor Say?: Improving Health Literacy to Protect Patient Safety. Joint Commission, 2007

36

Berkman et al, op cit.

37

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. Health Literacy Online: A

Guide to Writing and Designing Easy-to-Use Health Web Sites. Washington, D.C., 2010. Available at:

http://www.health.gov/healthliteracyonline/.

38

U.S. Congress. “H.R.1: American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009.” Obey, D. Available at: http://www.govtrack.us/

congress/bill.xpd?bill=h111-1.

Health Literacy Implications of the Affordable Care Act

16

identify and provide patient-specific education resources; and (3) health care providers using an EHR

must collect race and ethnicity data on their patients, using the OMB’s classification standards.

Public Health, Health Promotion, and Prevention & Wellness

TABLE 6: Provisions Related to Public Health, Health Promotion, and Prevention & Wellness

Section Number Provision Title

Sec. 2951 Maternal, infant, and early childhood home visiting programs

Sec. 2953 Personal responsibility education

Sec. 4001

N

ational Prevention, Health Promotion and Public Health Council

Sec. 4002 Prevention and Public Health Fund

Sec. 4003 Clinical and Community Preventive Services

Sec. 4004 Education and outreach campaign regarding preventive benefits

Sec. 4102 Oral healthcare prevention

a

ctivities

Sec. 4103 Medicare coverage of annual wellness visit providing a personalized prevention plan

Sec. 4107 Coverage of comprehensive tobacco cessation services for pregnant women in Medicaid

Sec. 4108 Incentives for prevention of chronic diseases in Medicaid

Sec. 4201 Community transformation grants

Sec. 4202 Healthy Aging/Living Well for Medicare

Sec. 4206 Demonstration project concerning individualized wellness plan

Sec. 4303 CDC and employer-based wellness programs

Sec. 4306 Funding for childhood obesity demonstration project

Sec. 10408 Grants for small businesses to provide comprehensive workplace wellness programs

Sec. 10413 Young women’s breast health awareness and support of young women diagnosed with breast

cancer

Sec. 10501

N

ational diabetes prevention program

ACA establishes a comprehensive framework for federal, community-based public health activities,

including a coordinating council, a national strategy, and a national education and outreach campaign.

The legislation also addresses prevention and wellness at state, community, clinic, and organizational

levels. Specifically, it:

Expands coverage of clinical preventive services under Medicare, Medicaid, and private health

insurance;

Encourages the development and expansion of personalized wellness programs by employers and

insurers;

Health Literacy Implications of the Affordable Care Act

17

Expands federal grantmaking and other public health activities directed at the prevention of

disease risk factors such as obesity and tobacco use, with a focus on community transformation;

and

Supports evidence review processes to determine whether specific clinical (e.g. cancer

screenings) and community-based prevention interventions (e.g. media campaigns) are effective.

Notably, the large national outreach and education undertaking to be led by the HHS and CDC under

Sec. 4004 will include a science-based media campaign; a chronic disease website to educate consumers;

a web-based tool for individuals to create personalized prevention plans; and an internet portal with

health risk assessment tools developed by academic entities. In addition, each state must design a public

awareness campaign to educate Medicaid enrollees about the availability and coverage of preventive

services, such as obesity-reduction programs for children and adults. To be successful, these

communication efforts should include the use of multiple media streams to reach diverse populations.

ACA also requires Medicaid health plans to cover tobacco cessation counseling and drug therapy for

pregnant women. States that include a package of recommended preventive services (as set by the U.S.

Preventive Services Task Force) for Medicaid-eligible adults will receive an enhanced federal match.

Medicare Part B will be required to cover personalized prevention services for elders, including chronic

disease testing and treatment, medication reconciliation, cognitive impairment assessments, and tailored

wellness guidance. Other related programs authorized in the ACA that promote prevention and target

specific populations or health gap areas include: a national oral health education campaign; early

mother-child visiting programs; teenage personal responsibility grants; the pregnancy assistance fund; a

national diabetes prevention program; childhood obesity-reduction initiatives; and centers for excellence

in depression. These programs will address health literacy to the extent that they are attentive to issues

of information usability, consumer engagement and cultural competency.

Although competencies around emergency preparedness and infectious disease are not a notable part of

ACA’s public health provisions, they should not be ignored during the implementation of national and

community-based public health efforts. For example, individuals with compromised health literacy are

likely less equipped to receive pertinent information or act expeditiously in the face of environmental

disasters and pandemic disease outbreaks.

39

,

40

Being healthy or learning how to become and stay healthy requires substantial self-activation, resources,

willpower, and lifestyle modification. These are challenging for any patient, let alone one with low

health literacy, who may encounter other structural barriers to good health. Such obstacles may include

substandard housing; transportation difficulty; low job availability; poor educational opportunities;

higher exposure to environmental toxins; involvement with violence and criminal justice;

discrimination and socio-cultural marginalization; and limited access to fresh, healthy foods. These social

problems and the circumstances of “place” have been shown to have a significant impact on the health

of the underserved, many of whom also face low literacy.

41

,

42

39

C. Zarcadoolas, J. Boyer, A. Krishnaswami, and A. Rothenberg (2007). “How Usable are Current GIS Maps: Communicating

Emergency Preparedness to Vulnerable Populations?” Journal of Homeland Security and Emergency Management, 2007.

40

C. Zarcadoolas, A. Pleasant, and D.S.Greer. Advancing Health Literacy: A Framework for Understanding and Action. San

Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 2006.

41

B. Smedley. Building Stronger Communities for Better Health: Moving from Science to Policy to Practice. Presentation at IOM

Workshop, 2010.

42

Andrulis et al. Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act: Advancing Health Equity for Racially and Ethnically Diverse

Populations. Joint Center for Political and Economic Studies. Washington DC, July 2010.

Health Literacy Implications of the Affordable Care Act

18

Innovations in Quality and the Delivery and Costs of Care

TABLE 7: Provisions Related to Innovations in Quality and the Delivery and Costs of Care

Section Number Provision Title

Direct Mentions of Health Literacy

Sec. 3501 Health care delivery system research; quality improvement technical assistance

Sec. 3506 Program to facilitate shared decision-making

Sample of Indirect Instances where Health Literacy could be addressed

Sec. 2703 State option to provide health homes for enrollees with chronic conditions

Sec. 3011

N

ational strategy

Sec. 3012 Interagency Working Group on Health Care Quality

Sec. 3013 Quality measure development

Sec. 3014 Quality measurement

Sec. 3015 Data collection; public reporting

Sec. 3021 Establishment of Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation within CMS

Sec. 3502 Grants or contracts to establish community health teams to support the patient-centered

medical home

Sec. 3510 Patient navigator program

Sec. 10331 Public reporting of performance information

Sec. 10333 Community-based collaborative care networks

There is no dearth of provisions in the ACA focused on improving health care quality and reducing

avoidable costs. The legislation identifies patient-centeredness, safety, efficiency, and equity as both

vehicles for and by-products of the quality effort. Except for two mentions of health literacy in provisions

regarding shared decision-making programs and dissemination of delivery system research, health literacy

is not explicitly featured in the bill’s language on quality. However, adults with low health literacy

average six percent more hospital visits, remain in the hospital two days longer and have annual health

care costs four times higher than those with proficient health literacy skills.

43

As such, literacy should be

a core consideration in discussions of quality improvement, health delivery redesign, and cost-reduction.

The legislation uses three broad mechanisms to address quality: (1) a national approach that identifies an

umbrella strategy, establishes a federal-level, inter-agency quality workgroup, sets an agenda for

measurement, and develops metrics; (2) delivery system redesign through efforts targeting improved care

coordination and new patient-centered care models such as the medical home; and (3) the reduction of

cost through increased payer and provider accountability across private and public programs (e.g., pay-

for-performance incentives and value-based purchasing structures).

43

Partnership for Clear Health Communication at the National Patient Safety Foundation. What is Health Literacy? Ask Me 3.

Available at: http://www.npsf.org/askme3/PCHC/what_is_health.php.

Health Literacy Implications of the Affordable Care Act

19

Health literacy issues should ideally be represented in the ACA-mandated inter-agency quality

workgroup to be convened by the President, and in the development of the national quality strategy (i.e.,

readability standards for all federal health program communications). Quality measure development and

endorsement efforts that will be spearheaded by AHRQ and CMS should gauge national health literacy

trends and their implications, as well as explore how new measures that identify and stratify low-literacy

risk groups can be used to improve care at the community, provider, plan, and hospital levels. The

support for public reporting mechanisms in ACA may also provide consumers with better, more readable

information about the performance of their health system, enabling more informed health care choices.

Many of the objectives of quality improvement — avoiding waste in the system; reducing the over- and

underuse of medications, diagnostic tests, and therapies; and improving patient safety — depend on the

patient’s ability to be an informed and active player in his or her care. For low-literate populations,

interacting with physicians, complying with medical guidance, and managing the disparate demands of

multiple providers in fragmented delivery systems is that much more challenging.

Other ACA components that ensure patient-centeredness, such as the shared decision-making program

and patient navigator services, should also resonate with health literacy advocates. Regional

collaborative networks, primary care extension hubs, health homes in Medicaid, and community health

teams to support the medical home would all be strengthened by concerted attention to patients with

low literacy, particularly those managing complex, co-morbid physical and mental health conditions.

Estimates suggest that 75 percent of those with chronic conditions have low health literacy.

44

One of the most promising windows of opportunity among the quality-oriented provisions is the newly

created Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation (CMI) within CMS. CMI will fund

demonstration programs that research, test, and expand innovations in payment and delivery system

improvement pilots. Given the prevalence of low literacy among individuals in publicly financed care,

particularly people with disabilities in Medicaid and those dually eligible for Medicaid and Medicare,

45

this could be a prime opportunity to test health literacy innovations among high-risk populations such as

pregnant women or elders with multiple medications. Such demonstrations could convey to federal and

state policymakers the mediating power of health literacy to improve quality and reduce costs. This could

also help demonstrate the business case for further investments in health literacy by health plans and

accountable care organizations serving these populations.

Given the evidence base around populations disproportionately affected by low health literacy,

Medicaid, Medicare, and Veterans Administration programs may present the best targets of opportunity

for making the case. The Veterans Administration is a closed system with considerable data capacity, but

might pose problems for generalizability; while Medicare is still largely a fee-for-service system, which

provides few leverage points for concerted action. The 7.5 million individuals dually enrolled in

Medicaid and Medicare could benefit from health literacy interventions given their age and complex

health needs, but these “duals” are generally not in integrated care management programs that have

enormous incentives to prevent the exacerbation of illness and disability associated with low health

literacy. However, 71 percent of Medicaid’s 60 million beneficiaries are enrolled in managed care;

46

as the

nation’s largest purchaser of health care, Medicaid could use its leverage to promote innovations in this

arena. Medicaid managed care organizations already have the incentives to address health literacy,

especially for those with complex conditions. But, to date, none have demonstrated using readily

44

Hsu. The Health Literacy of U.S. Adults Across GED Credential Recipients, High School Graduates, and Non–High School

Graduates. American Council on Education. GED Testing Service, 2008.

45

Baker et. al. “Health Literacy and Mortality among Elderly Persons.” Archives of Internal Medicine (2007), 167(14):1503-1509.

46

Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. “Medicaid Managed Care

Penetration Rates by State as of June 30, 2008.” Special data request, August 2009.

Health Literacy Implications of the Affordable Care Act

20

available and easy-to-administer literacy assessment tools (e.g., the short TOHFLA) to: 1) identify and

stratify a high-risk population with low literacy skills, and 2) design interventions to support health

management and consequently avoid costly exacerbations, hospitalizations and institutionalizations.

Best Practices: “What Are My Medi-Cal Choices?”

Health Research for Action (HRA), a center at UC Berkeley’s School of Public Health, was funded by the

California Department of Health Care Services (DHCS) to create easy-to-read and understandable

information for seniors and people with disabilities on Medi-Cal, about their Medi-Cal choices. This specific

population could choose between Regular Medi-Cal (also known as Fee for Service) and Medi-Cal Managed

Care Plans. The goals of this project were to:

1. Use participatory research to develop a guidebook that informed seniors and people with

disabilities on Medi-Cal about their unique Medi-Cal choices.

2. Promote informed choice between Medi-Cal fee for service and Medi-Cal Managed Care delivery

systems.

HRA conducted extensive formative research to understand how seniors and people with disabilities learn

and make decisions about their Medi-Cal delivery options. Findings informed HRA’s development of a draft

consumer guidebook called “What Are My Medi-Cal Choices?” in English, Spanish, and Chinese. The

formative research used a participatory model where beneficiaries and other stakeholders were consulted in

the content and layout of the guidebook. HRA conducted 51 key informant interviews with stakeholders as

well as extensive qualitative research with Medi-Cal beneficiaries including 24 one-on-one interviews, 18

focus groups, and 36 one-on-one usability tests. This formative research was conducted in English, Spanish,

Mandarin, Cantonese, and American Sign Language. Formative research findings showed that that English-,

Spanish- and Chinese-speaking Medi-Cal recipients who are seniors or people with disabilities had very

little knowledge about their Medi-Cal choices and negative attitudes about managed care health plans.

Several areas of unmet information needs and primary areas of concern for SPD beneficiaries when faced

with Medi-Cal choices were also identified. In addition to the above formative research, an advisory group

that included disability advocates, managed care plan representatives, health care providers, policymakers,

and Medi-Cal beneficiaries provided guidance and feedback on the research, guidebook, the dissemination

process, and complementary interventions.

The Department of Health Care Services disseminated the guidebook through a direct mailing to

beneficiaries in the target population and via partner organizations. The final guidebook was developed in

12 threshold languages, plus alternative formats including Braille (English and Spanish only) and audio,

including MP3, cassette, and CD (all 12 languages).

HRA conducted a multi-lingual, mixed-methods evaluation of the final guidebook including 10 focus

groups, 28 stakeholder interviews, and a randomized control trial telephone survey. At six weeks post-

dissemination, the intervention group showed significantly higher increases in knowledge, confidence,

positive attitudes about, and intentions to consider changing to a Medi-Cal health plan than did the control

group. Overall, the findings provided strong evidence that the guidebook was an effective and low-cost way

to improve recipients’ abilities to make more informed Medi-Cal choices.

In 2008, the Institute for Healthcare Advancement jointly awarded HRA and the DHCS the national first place

award for Health Literacy for their work on the consumer guidebook.

Health Literacy Implications of the Affordable Care Act

21

III. Conclusion

he ACA is not a landmark piece of legislation for health literacy, but with its attention to increased

coverage, quality improvement and cost reduction, it creates opportunities for bringing cultural

competency, disparities, and health literacy to the fore. It establishes momentum for investments in

innovation among state agencies, payers, providers, regulators, advocacy groups, and others to improve

care in many ways, including patient-centered high quality care. Organizations promoting health literacy

will not be armed with forceful legislative or with regulatory mandates or with designated resources, so

they will have to continue to find ways to make the case for greater investment and action by both

public and private stakeholders in our health care system.

The ACA does create opportunities for driving home the importance of health literacy in all of the key

domains of health and health care identified earlier:

1. The Coverage Expansion: Establishing what is essentially universal coverage for 16 million

Americans up to 133 percent of FPL and subsidized insurance options for another 16 million low

income Americans will only be successful if the newly eligible individuals can understand their

options and navigate the enrollment process.

2. Equity: Moving toward universal coverage and creating the same “floor” for all of our lowest-

income populations should help address some of the fundamental disparities in access to care in

this country, but as the legislation underscores, that will depend on the attention our health care

delivery system pays to cultural differences, language, and by extension, literacy.

3. Workforce: The provider training provisions in ACA related to disparities, cultural competency,

and patient-centeredness all present opportunities for bringing greater attention to health

literacy.

4. Health care Information: From medication management to provider performance rating, patient

information must be presented at reading and numeracy levels accessible to millions of

Americans with low literacy skills.

5. Public Health and Wellness: The preparation and presentation (whether in print, electronically,

or otherwise) of consumer information on issues ranging from prevention to emergency

preparedness must be done with low literacy in mind.

6. Quality Improvement: The ACA’s emphasis on developing, testing and spreading best practices

for improving quality and reducing costs presents many new opportunities for making the case for

investments in health literacy.

T

Health Literacy Implications of the Affordable Care Act

22

IV. Appendices

*

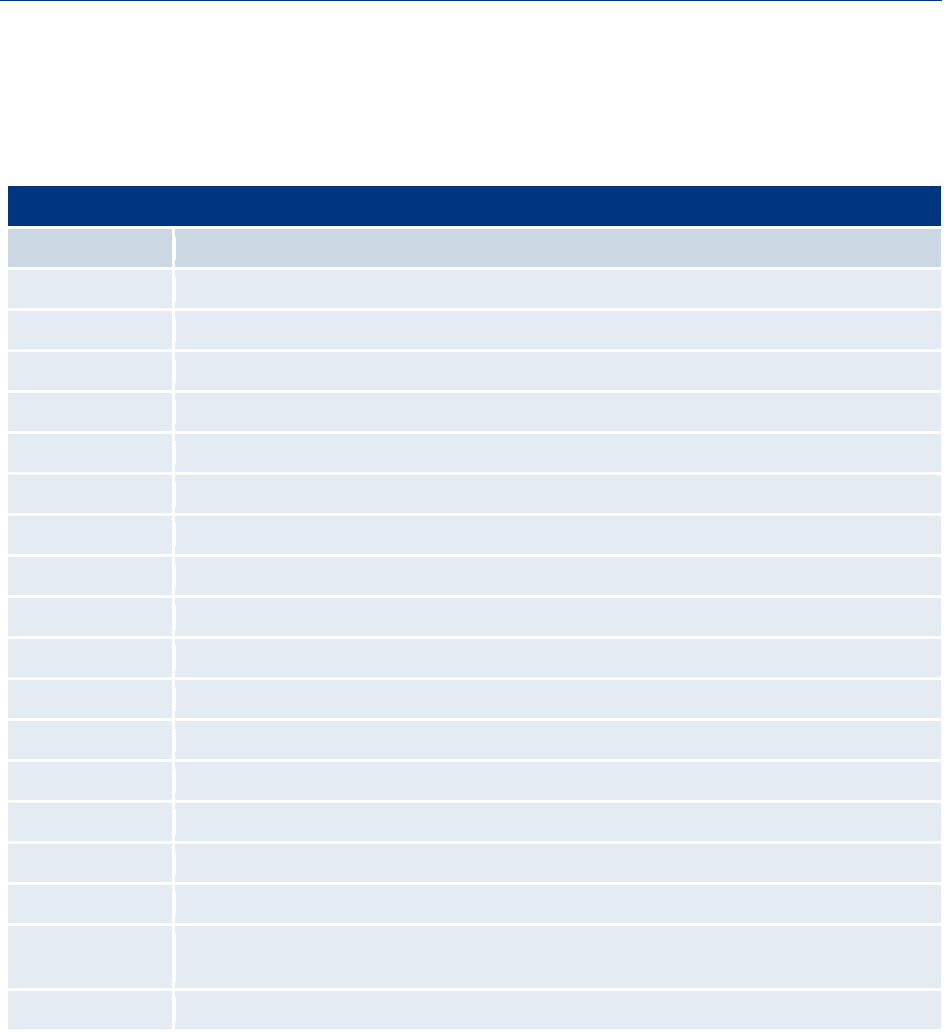

Appendix A: Summary of ACA Provisions with Potential Implications for Health

Literacy

Insurance Reform, Outreach, and Enrollment

Sec. 1002. Health insurance consumer information. The Secretary shall award grants to States to

enable them (or the Exchange) to establish, expand, or provide support for offices of health insurance

consumer assistance or health insurance ombudsman programs. These independent offices will assist

consumers with filing complaints and appeals, educate consumers on their rights and responsibilities, and

collect, track, and quantify consumer problems and inquiries.

Sec. 1103. Immediate information that allows consumers to identify affordable coverage options.

Establishes an Internet portal for beneficiaries to easily access affordable and four comprehensive

coverage options. This information will include eligibility, availability, premium rates, cost sharing, and

the percentage of total premium revenues spent on health care, rather than administrative expenses, by

the issuer. Section 10102 clarifies that the internet portal shall be available to small businesses and shall

contain information on coverage options available to small businesses.

Sec. 1311. Affordable choices of health benefit plans. Requires the Secretary to award grants, available

until 2015, to States for planning and establishment of American Health Benefit Exchanges. By 2014,

requires States to establish an American Health Benefit Exchange that facilitates the purchase of

qualified health plans and includes a SHOP Exchange for small businesses.

Sec. 1401. Refundable tax credit providing premium assistance for coverage under a qualified health

plan. Amends the Internal Revenue Code to provide tax credits to assist with the cost of health

insurance premiums.

Sec. 1413. Streamlining of procedures for enrollment through an Exchange and State Medicaid,

CHIP, and health subsidy programs. Requires the Secretary to establish a system for the residents of

each State to apply for enrollment in, receive a determination of eligibility for participation in, and

continue participation in, applicable State health subsidy programs. The system will ensure that if any

individual applying to an Exchange is found to be eligible for Medicaid or a State children’s health

insurance program (CHIP), the individual is enrolled for assistance under such plan or program.

Sec. 1513. Shared responsibility for employers. As amended by the Reconciliation Act, requires an

employer with at least 50 full-time employees that does not offer coverage and has at least one full-time

employee receiving a premium assistance tax credit to make a pay

ment of $2,000 per full-time employee.

Includes the number of full-time equivalent employees for purposes of determining whether an employer

has at least 50 employees. Exempts the first 30 full-time employees for the purposes of calculating the

amount of the payment. Section 10106 clarifies that the calculation of full-time workers is made on a

*

Adapted from the following:

• Communication with S. Rosenbaum (August – September 2010), Hirsh Professor and Chair of the Health Policy Department,

George Washington University.

• Democratic Policy Committee, U.S. Senate. Affordable Care Act: Section-by-Section Analysis with Changes Made by Title X

and Reconciliation. Updated September 17, 2010. Available at: http://dpc.senate.gov/dpcissue-.

• E. Williams and C. Redhead. Public Health Workforce, Quality, and Related Provisions in the Patient Protection and

Affordable Care Act (PPACA). Congressional Research Service (CRS) Report for Congress. 7-5700. June 2010. Available at:

http://www.crs.gov.

Health Literacy Implications of the Affordable Care Act

23

monthly basis. The Reconciliation Act eliminates the penalty for waiting periods before an employee may

enroll in coverage. An employer with at least 50 employees that does offer coverage but has at least one

full-time employee receiving the premium assistance tax credit will pay the lesser of $3,000 for each of

those employees receiving a tax credit or $2,000 for each of their full-time employees total, not including

the first 30 workers. The Secretary of Labor shall conduct a study to determine whether employees’ wages

are reduced by reason of the application of the assessable payments.

Sec. 2001. Medicaid coverage for the lowest income populations.

Creates a new State option to provide Medicaid coverage through a State plan amendment beginning on

April 1, 2010, as amended by Section 10201. Eligible individuals include: all non-elderly, non-pregnant

individuals who are not entitled to Medicare (e.g., childless adults and certain parents). Creates a new

mandatory Medicaid eligibility category for all such “newly-eligible” individuals with income at or below

133 percent of the FPL beginning January 1, 2014. As of January 1, 2014, the mandatory Medicaid

income eligibility level for children ages 6 to 19 changes from 100 percent to 133 percent FPL. Effective

April 1, 2010, states can provide Medicaid coverage to all non-elderly individuals above 133 percent of

FPL through a State plan amendment.

Sec. 2715. Development and utilization of uniform explanation of coverage documents and

standardized definitions. Requires the Secretary to develop standards for use by health insurers in

compiling and providing an accurate summary of benefits and explanation of coverage for applicants,

policyholders or certificate holders, and enrollees. Standards must be in a uniform format, using language

that is easily understood by the average enrollee, and must include uniform definitions of standard

insurance and medical terms. The explanation must also describe any cost-sharing, exceptions,

reductions, and limitations on coverage, and examples of common benefits scenarios.

Sec. 3306. Funding outreach and assistance for low-income programs. Provides $45 million for

outreach and education activities to State Health Insurance Programs, Administration on Aging, Aging

Disability Resource Centers and the National Benefits Outreach and Enrollment.

Sec. 5000A. Requirement to maintain minimum essential coverage. Requires individuals to maintain

minimum essential coverage beginning in 2014. As amended by Section 1002 of the Reconciliation Act,

failure to do so will result in a penalties, with exceptions and exemptions.

Individual Protections, Equity and Special Populations

Sec. 1557. Nondiscrimination. Protects individuals against discrimination under the Civil Rights Act,

the Education Amendments Act, the Age Discrimination Act, and the Rehabilitation Act, through

exclusion from participation in or denial of benefits under any health program or activity.

Sec. 2405. Funding to expand State Aging and Disability Resource Centers. Appropriates, to the

Secretary of HHS, $10 million for each of FY 2010 - 2014 to carry out Aging and Disability Resource

Center (ADRC) initiatives.

Sec. 4302. Understanding health disparities; data collection and analysis. Ensures that any ongoing or

new Federal health program achieve the collection and reporting of data by race, ethnicity, primary

language and any other indicator of disparity.

Health Literacy Implications of the Affordable Care Act

24

Sec. 6105. Standardized complaint form. Requires the Secretary to develop a standardized complaint

form for use by nursing home residents (or a person acting on a resident’s behalf) in filing complaints

with a State survey and certification agency and a State long-term care ombudsman program. States

would also be required to establish complaint resolution processes.

Sec. 6121. Dementia and abuse prevention training. Requires facilities to include dementia

management and abuse prevention training in pre-employment initial training for permanent and

contract or agency staff, and if the Secretary determines appropriate, in ongoing in-service training.

Sec. 6301. Patient-Centered Outcomes Research. Establishes a private, nonprofit entity (the Patient-

Centered Outcomes Research Institute) governed by a public-private sector board to identify priorities

for and provide for the conduct of comparative outcomes research. Requires the Institute to ensure that

subpopulations are appropriately accounted for in research designs.

Sec. 6703. Elder Justice. Requires the Secretary of HHS, in consultation with the Departments of

Justice and Labor, to award grants and carry out activities that provide greater protection to those

individuals seeking care in facilities that provide long-term services and supports and provide greater

incentives for individuals to train and seek employment at such facilities.