CIVIL ENGINEERING STUDIES

Illinois Center for Transportation Series No. 24-2014

UILU-ENG-2024-2014

ISSN: 0197-9191

Effects of Nontraditional Messages in

Dynamic Message Signs on Improving

Safety, Compliance, and Avoiding

Distraction

Prepared By

Yuhui Zhai

Yanfeng Ouyang

University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign

Research Report No. FHWA-ICT-24-012

A report of the findings of

ICT PROJECT R27-SP55

Development of Guidelines for Messages in Dynamic

Messaging Signs to Improve Safety, Compliance, and Avoid

Distraction

https://doi.org/10.36501/0197-9191/24-014

Illinois Center for Transportation

May 2024

TECHNICAL REPORT DOCUMENTATION PAGE

1. Report No.

FHWA-ICT-24-012

2. Government Accession No.

N/A

3. Recipient’s Catalog No.

N/A

4. Title and Subtitle

Effects of Nontraditional Messages in Dynamic Message Signs on Improving Safety,

Compliance, and Avoiding Distraction

5. Report Date

May 2024

6. Performing Organization Code

N/A

7. Authors

Yuhui Zhai, Yanfeng Ouyang (https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5944-2044)

8. Performing Organization Report No.

ICT-24-014

UILU-2024-2014

9. Performing Organization Name and Address

Illinois Center for Transportation

Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering

University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign

205 North Mathews Avenue, MC-250

Urbana, IL 61801

10. Work Unit No.

N/A

11. Contract or Grant No.

R27-SP55

12. Sponsoring Agency Name and Address

Illinois Department of Transportation (SPR)

Bureau of Research

126 East Ash Street

Springfield, IL 62704

13. Type of Report and Period Covered

Final Report 6/1/23–5/31/24

14. Sponsoring Agency Code

15. Supplementary Notes

Conducted in cooperation with the U.S. Department of Transportation, Federal Highway Administration.

https://doi.org/10.36501/0197-9191/24-014

16. Abstract

This project develops capability for future studies on the effects of nontraditional messages in dynamic message signs on

improving driver safety and compliance and avoiding distractions. An online survey and a driving simulation game were designed,

and a pilot run was conducted with a small number of students in the University of Illinois Urbana Champaign. Survey responses

and simulation data were analyzed to reveal preliminary findings on notable effectiveness across different types of messages

(e.g., humorous, emotionless, negative). The pilot study also provides guidelines and recommendations for running a large-scale

survey and simulation game in the future.

17. Key Words

Dynamic Message Signs, Driving Simulation, Safety and

Compliance, Nontraditional Messages

18. Distribution Statement

No restrictions. This document is available through the

National Technical Information Service, Springfield, VA

22161.

19. Security Classif. (of this report)

Unclassified

20. Security Classif. (of this page)

Unclassified

21. No. of Pages

40 + appendices

22. Price

N/A

Form DOT F 1700.7 (8-72) Reproduction of completed page authorized

i

ACKNOWLEDGMENT, DISCLAIMER, MANUFACTURERS’ NAMES

This publication is based on the results of ICT-R27-SP55: Development of Guidelines for Messages in

Dynamic Messaging Signs to Improve Safety, Compliance, and Avoid Distraction. ICT-R27-SP55 was

conducted in cooperation with the Illinois Center for Transportation; the Illinois Department of

Transportation; and the U.S. Department of Transportation, Federal Highway Administration.

The research team thanks the Technical Review Panel (TRP) for the guidance, direction, and support.

Members of the TRP were the following:

• Sean Martschinke, TRP Chair, Illinois Department of Transportation

• Alan Ho, Federal Highway Administration

• Kyle Armstrong, Illinois Department of Transportation

• Rochelle Gillespie, Illinois Department of Transportation

• Lisa Heaven-Baum, Illinois Department of Transportation

• Tracy Lillard, Illinois Department of Transportation

The contents of this report reflect the view of the authors, who are responsible for the facts and the

accuracy of the data presented herein. The contents do not necessarily reflect the official views or

policies of the Illinois Center for Transportation, the Illinois Department of Transportation, or the

Federal Highway Administration. This report does not constitute a standard, specification, or

regulation.

ii

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

This project focused on guidelines for using nontraditional messages in dynamic message signs to

improve driver safety and compliance and to avoid distractions. The purpose of this project was to

help Illinois Department of Transportation (IDOT) determine if nonstandard messages (i) cause a

change in driver behavior and reduce crash frequency in the area of the signage in Illinois, (ii) increase

engagement of the motoring public with safer driving practices, and (iii) have a lasting impact on

drivers who see the messages (i.e., does the message stick).

This pilot project included three main tasks. First, the researchers conducted a literature review to

investigate past studies on how drivers change behaviors upon seeing different types of dynamic

messages and to learn from similar projects that experiment on the effect of drivers’ behavior change

caused by dynamic message signs. Second, they developed a web-based questionnaire and

simulation game to capture drivers’ opinions and behaviors toward dynamic messages in a semi-

realistic environment. The web-based questionnaire collected drivers’ demographic and

socioeconomic information as well as their understanding, impression, and acceptance of

nonstandard messages. The web-based simulation game provided participants with either an urban

or a rural freeway driving environment to test their reactions to dynamic messages in an ongoing

traffic stream. Third, the researchers conducted a preliminary proof-of-concept data analysis to

demonstrate effectiveness of nontraditional messages and to develop a better understanding of how

dynamic messages influence driver behaviors. The findings were used to provide suggestions on how

IDOT may systematically present information on dynamic message signs in practice.

Some of the key findings are listed below.

• The literature review revealed that different nontraditional messages may have mixed

impacts on encouraging safe driving practices.

o Nontraditional messages were more memorable than traditional messages and helped

drivers comply with speed limits.

o In certain cases, nontraditional messages may have also distracted drivers and resulted in

queues in traffic, and they could cause risks and hazards by inducing varying speeds.

• The proposed online survey and driving game seemed to be able to protect the privacy of

respondents and were sufficiently robust and ready for larger scale adoption.

o The driving game could simulate a rather realistic and complex environment. The

configuration could be changed easily to test the influence of specific factors (e.g., lighting

conditions, traffic congestion, road geometry, speed limits, and weather conditions).

o Any type of nontraditional messages could be easily loaded and tested in the driving

game.

iii

o The driving game recorded real-time data trajectories that could be used for more

sophisticated analysis (e.g., data mining, deep learning) than traditional questionnaire

surveys.

• Our preliminary analysis of collected data from a small-scale survey showed the following:

o Humorous messages should be avoided in encouraging drivers to decrease speed.

o Emotionless messages were effective in discouraging drivers to speed.

o Humorous messages were effective in encouraging drivers to reduce text messaging and

calling when the driving speed is around 60–90 mph.

o Humorous messages should be avoided in encouraging drivers to reduce honking when

the driving speed is around 60–90 mph.

o Negative (warning) messages were effective in encouraging drivers to buckle up when the

driving speed is lower than 60 mph.

Additional statistical tests with alternative grouping of the messages (humorous vs. negative) also

generate largely consistent findings. This study laid the foundation for a large-scale survey/game and

comprehensive synthesis of collected data, which we expect to be carried out by IDOT in the coming

months. The preliminary literature review and results of the driver survey/experiment provided

preliminary recommendations for IDOT on the most effective messages for Illinois. The results

suggested that proper types of nontraditional messages (especially negative and humorous ones)

could be effective in causing changes in driver behavior and increasing safety compliance.

iv

TABLE OF CONTENTS

CHAPTER 1: BACKGROUND .................................................................................................. 1

CHAPTER 2: LITERATURE REVIEW ......................................................................................... 3

CHAPTER 3: SURVEY/GAME DESIGN ..................................................................................... 5

ONLINE GAME DESIGN .............................................................................................................5

Basic GUI Design........................................................................................................................... 5

Dynamic Messages ....................................................................................................................... 9

QUESTIONNAIRE .................................................................................................................... 11

CHAPTER 4: PILOT SURVEY RESULTS ................................................................................... 14

ONLINE SIMULATION GAME RESULTS ..................................................................................... 14

QUESTIONNAIRE DATA ........................................................................................................... 21

Demographic Information ......................................................................................................... 21

Socioeconomic Information ....................................................................................................... 22

Driving Behavior Information .................................................................................................... 24

Impression on Nontraditional Messages ................................................................................... 26

CHAPTER 5: PRELIMINARY DATA ANALYSIS ........................................................................ 30

AVERAGE SPEED REDUCTION .................................................................................................. 31

SPEEDING ............................................................................................................................... 32

PHONE INTERACTIONS ........................................................................................................... 34

HONKING ............................................................................................................................... 35

SEAT BELT USE........................................................................................................................ 36

ALTERNATIVE MESSAGE CATEGORIES ..................................................................................... 37

CHAPTER 6: CONCLUSION .................................................................................................. 39

REFERENCES ....................................................................................................................... 40

APPENDIX A: NONTRADITIONAL MESSAGES ....................................................................... 41

APPENDIX B: CONSENT DOCUMENT FOR THE GAME/SURVEY ............................................ 45

APPENDIX C: ALTERNATIVE MESSAGE GROUPS .................................................................. 48

v

LIST OF FIGURES

Figure 1. Screenshot. The login page of the simulation game. ................................................................ 6

Figure 2. Screenshot. Basic GUI design for the online simulation game. ................................................. 7

Figure 3. Screenshot. Nontraditional messages shown on a dynamic message sign. ............................. 7

Figure 4. Screenshot. Panels with and without alarms in the online simulation game. .......................... 8

Figure 5. Screenshot. Phone interfaces in the simulation game. ............................................................. 9

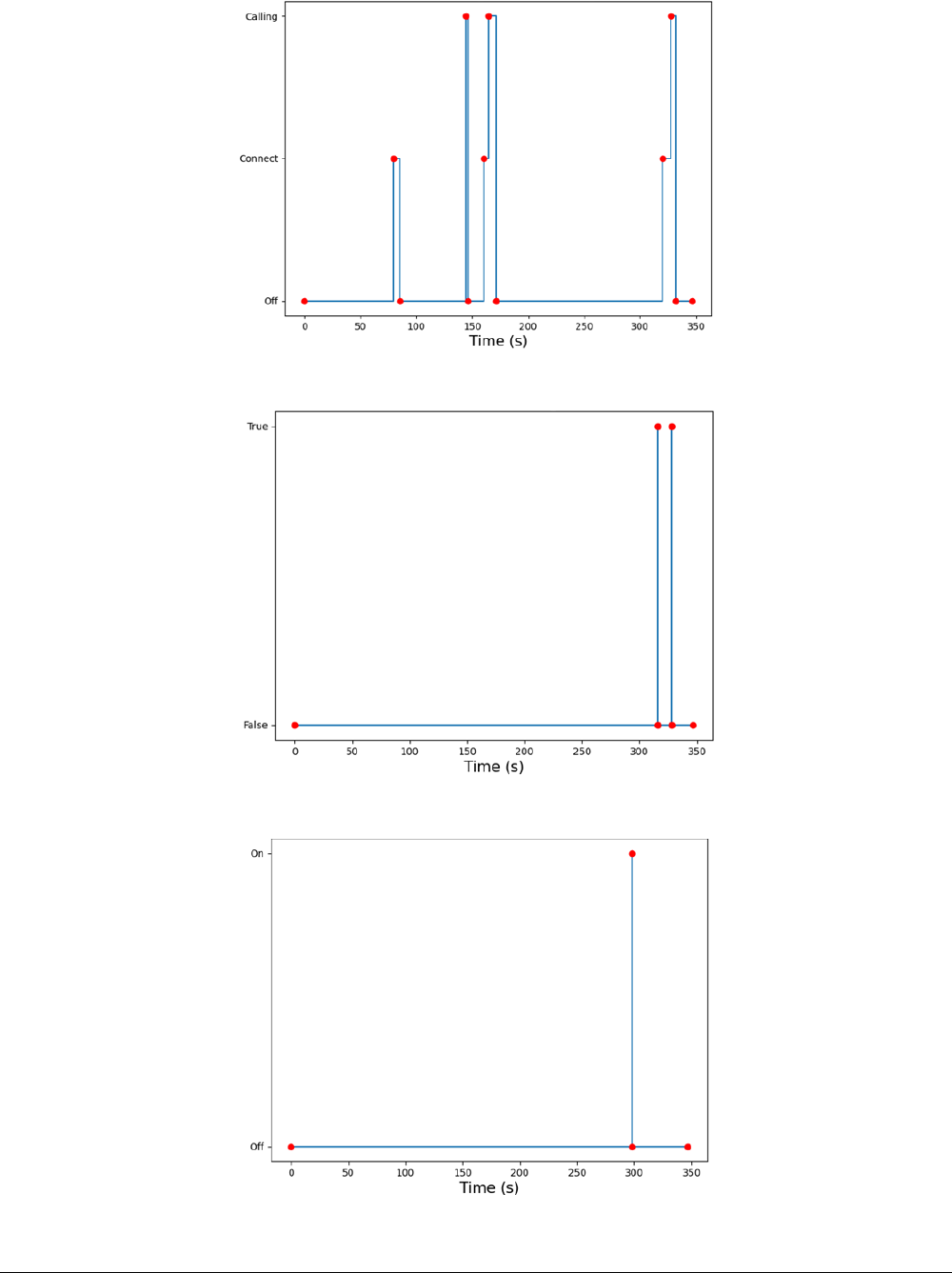

Figure 6. Graph. Sample data records from the same participant. ........................................................ 18

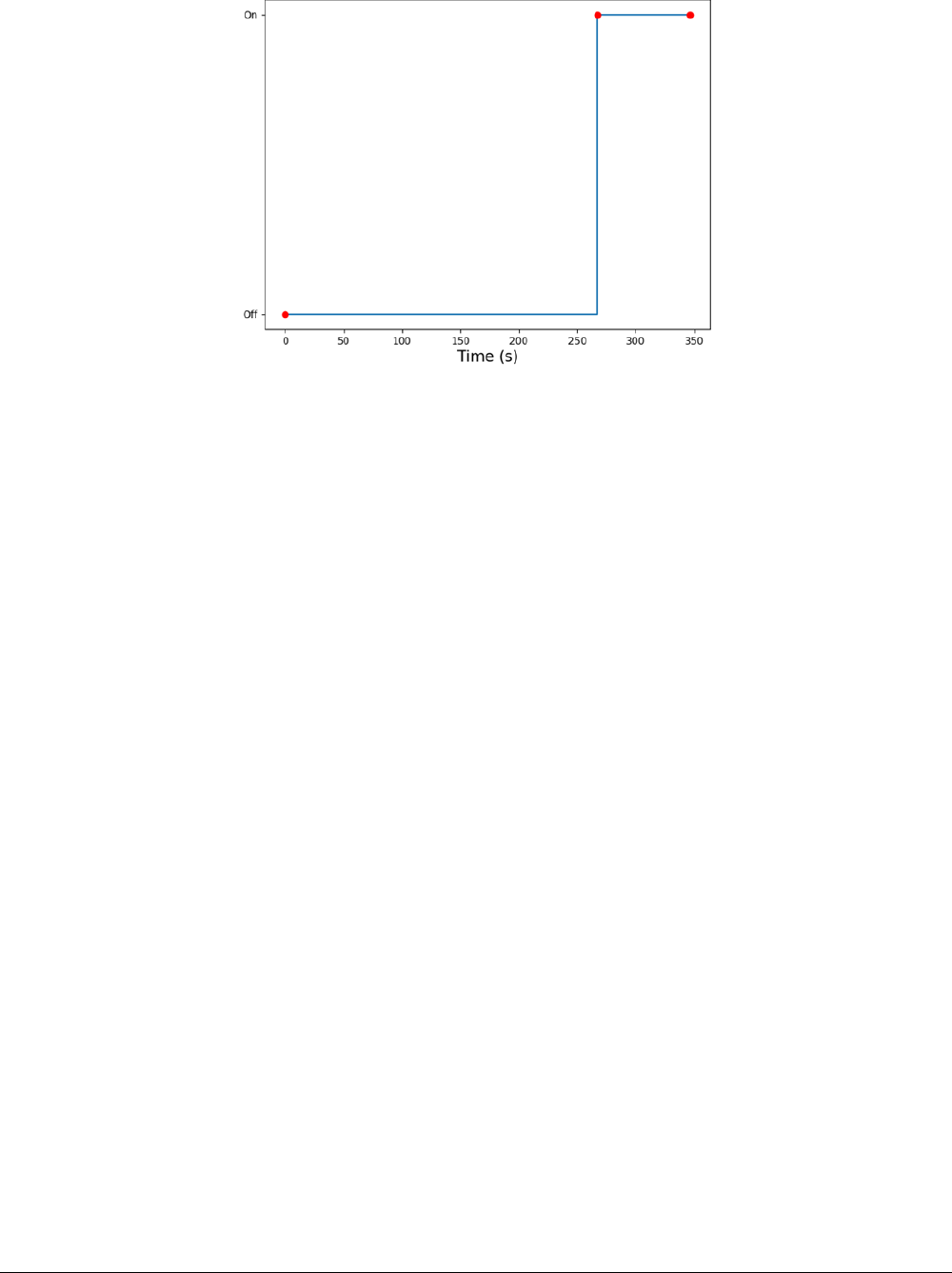

Figure 7. Graph. Histograms of attributes among 118 participants....................................................... 20

Figure 8. Graph. Demographic information of respondents. ................................................................. 22

Figure 9. Graph. Socioeconomic information of respondents. .............................................................. 24

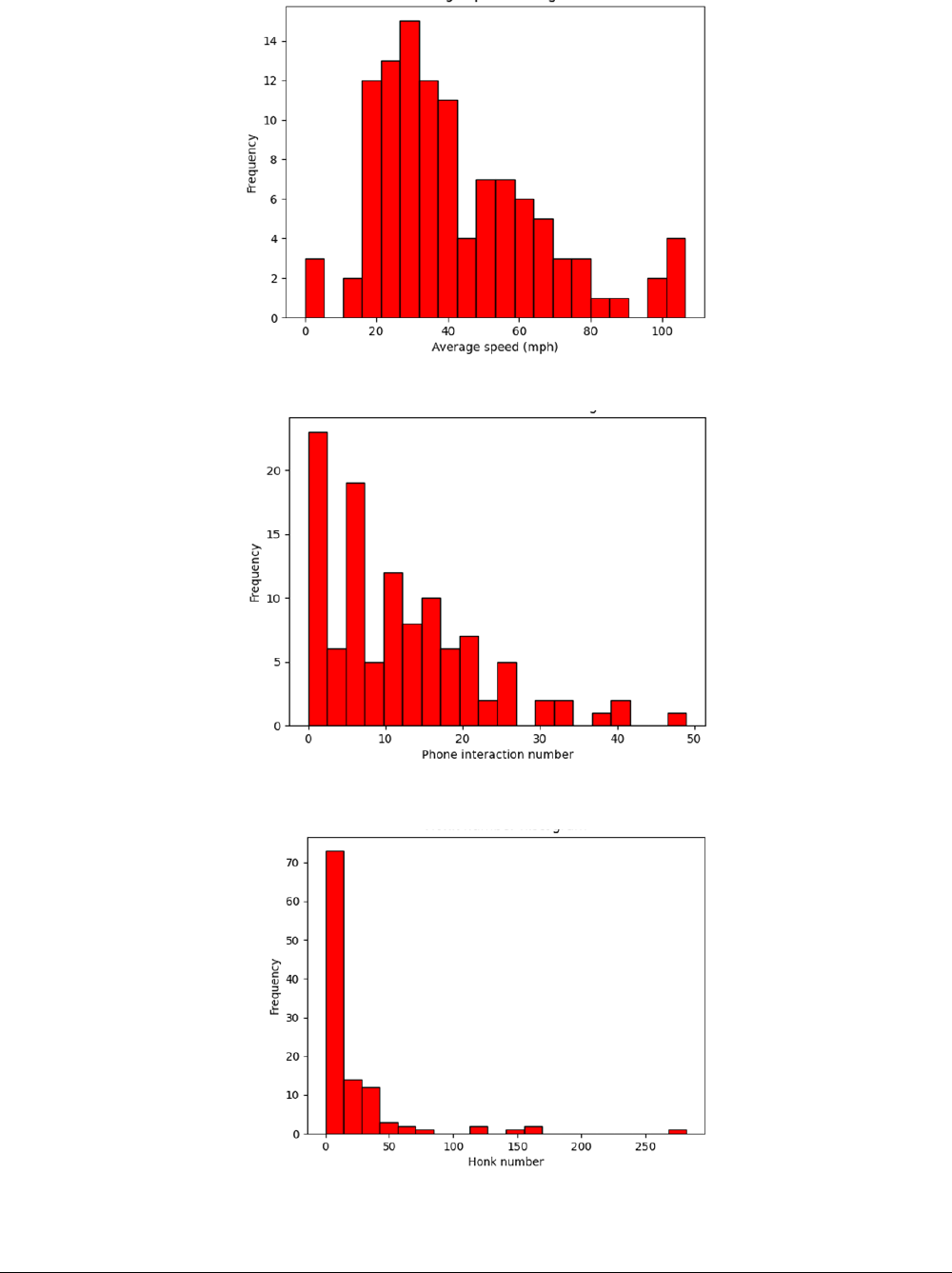

Figure 10. Graph. Driving behaviors information of respondents. ........................................................ 25

Figure 11. Graph. Opinions toward nontraditional messages in the questionnaire. ............................. 28

Figure 12. Graph. Most memorable and inappropriate messages. ....................................................... 28

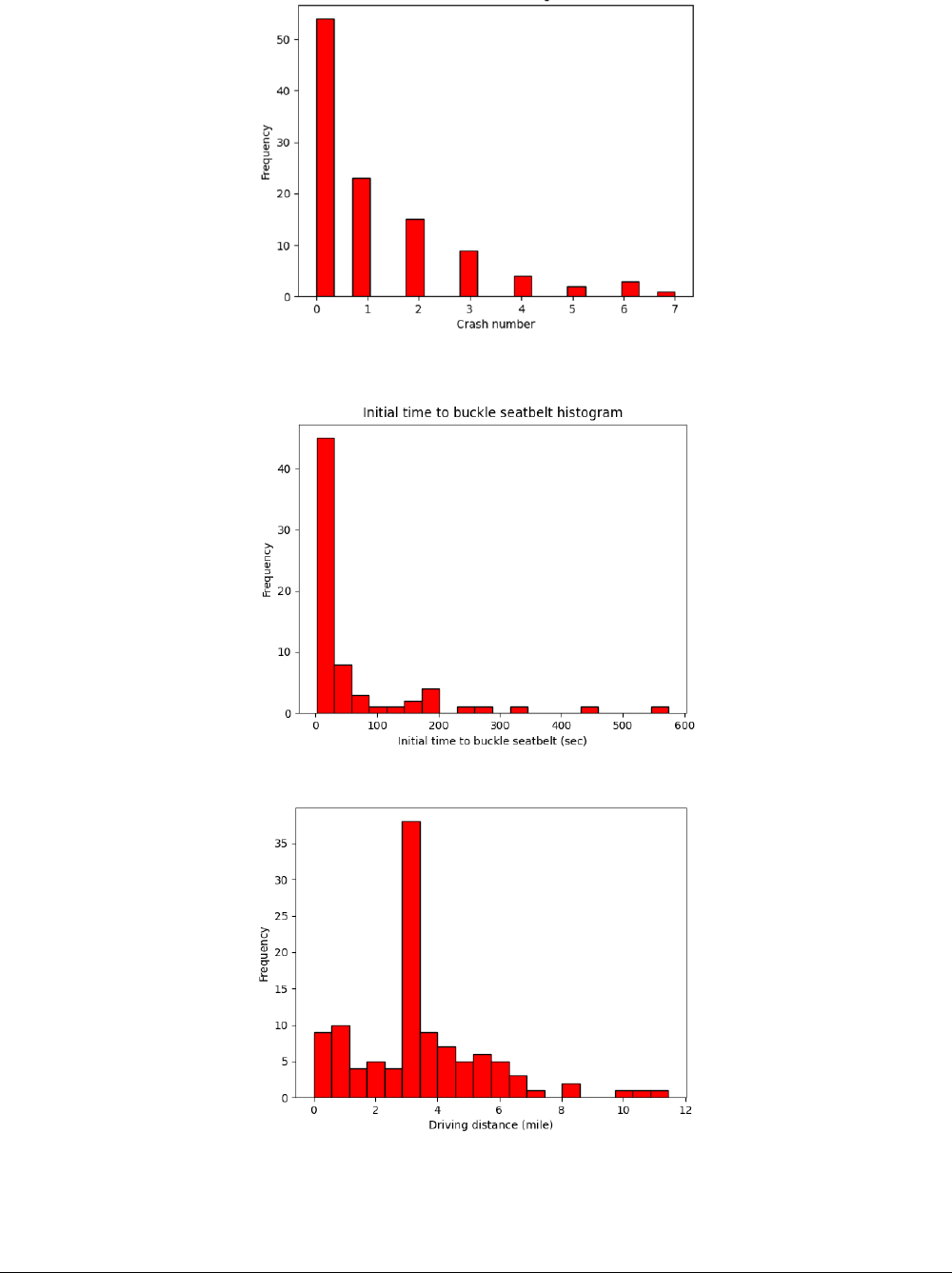

Figure 13. Graph. Quantitative analysis of speed reduction by message signs. .................................... 31

Figure 14. Graph. Effectiveness of three emotions in general safe driving to reduce speed. ............... 32

Figure 15. Graph. Effectiveness of three emotions to avoid speeding. ................................................. 33

Figure 16. Graph. Effectiveness of three emotions in distracted driving messages to reduce phone use.

................................................................................................................................................................ 34

Figure 17. Graph. Effectiveness of three emotions in general safe driving to reduce honking. ............ 35

Figure 18. Graph. Effectiveness of three emotions in encouraging seat belt use. ................................ 36

vi

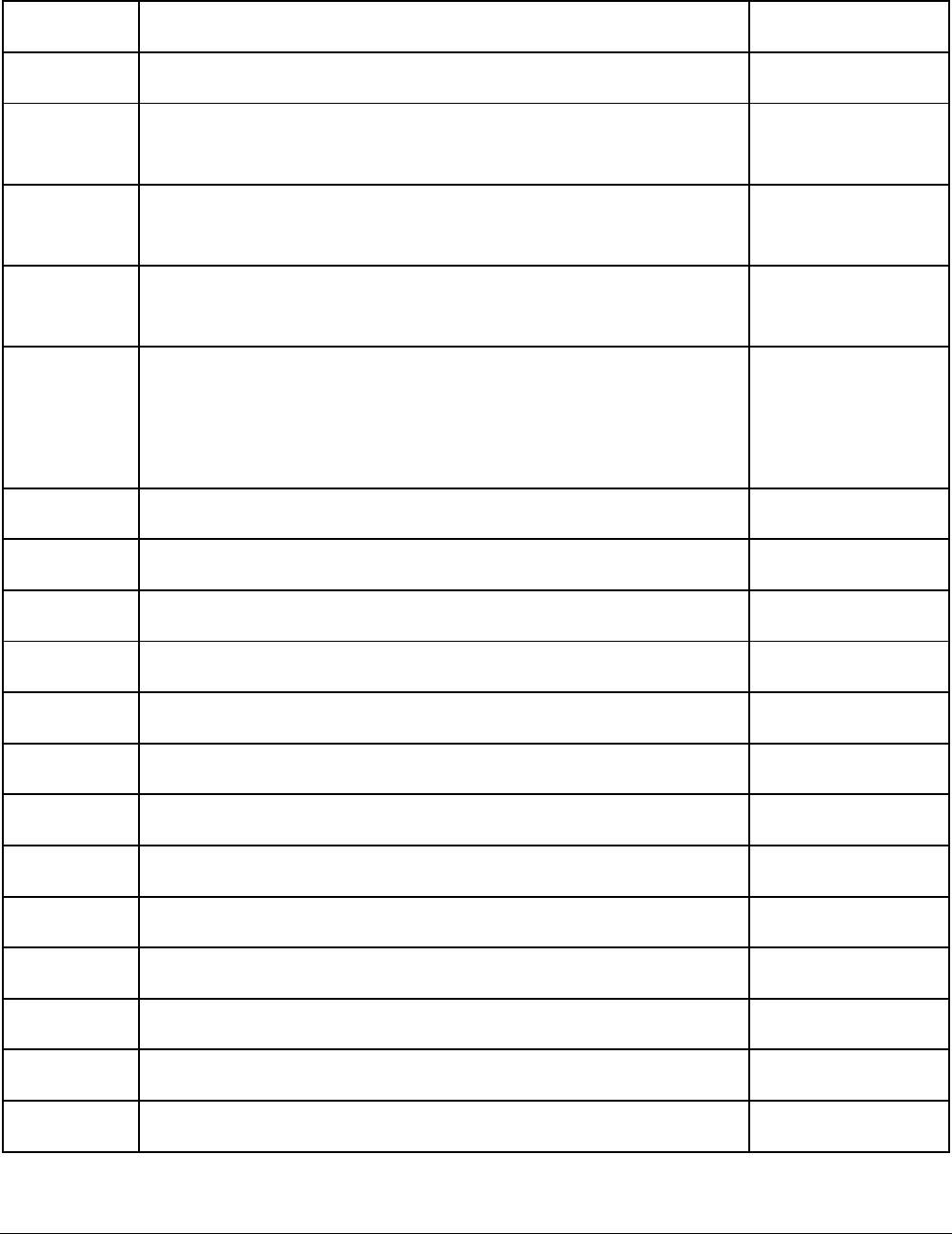

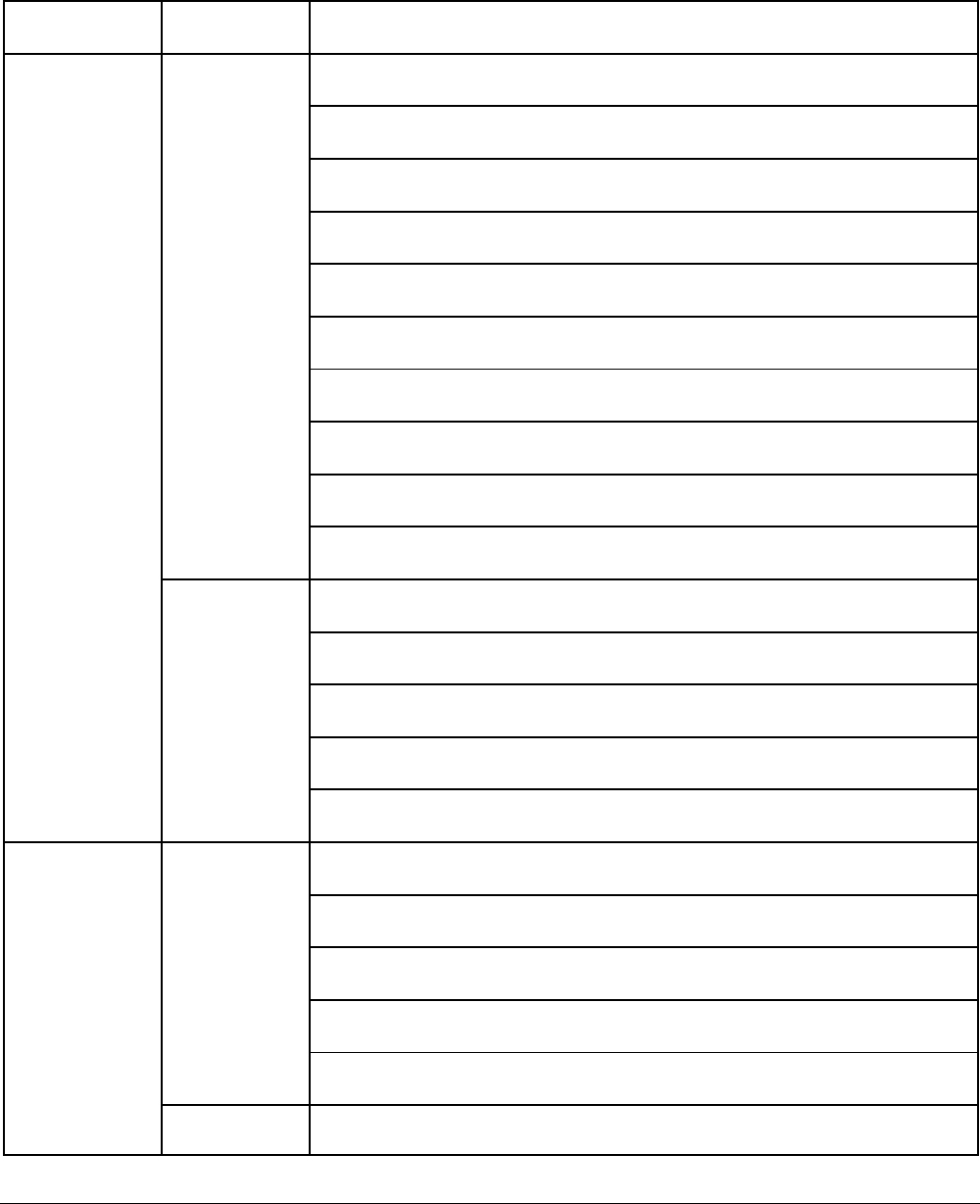

LIST OF TABLES

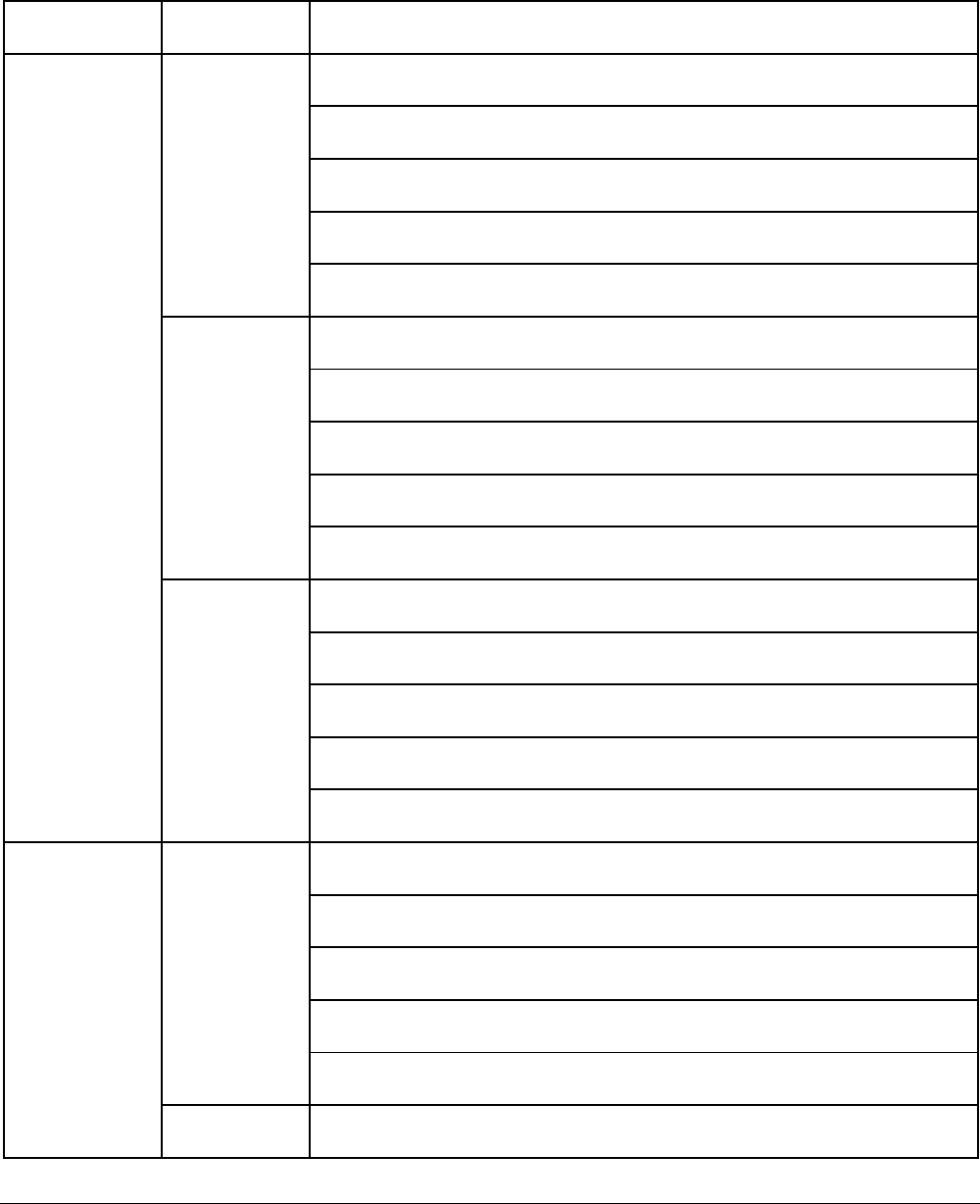

Table 1. Nontraditional Messages Grouped by Target Behavior and Emotion ...................................... 10

Table 2. Online Questionnaire Questions and Corresponding Categories ............................................. 12

Table 3. Sample Record of Shown Nontraditional Messages from One Simulation Game ................... 15

Table 4. Sample Responses on Most Memorable and Inappropriate Messages ................................... 29

Table 5. Two-Sample t-test between Three Emotions in Reducing Speed ............................................ 32

Table 6. Two-Sample t-test between Three Emotions to Avoid Speeding ............................................. 33

Table 7. Two-Sample t-test between Three Emotions in Distracted Driving Messages to Reduce Phone

Use .......................................................................................................................................................... 34

Table 8. Two-Sample t-test between Three Emotions in General Safe Driving to Reduce Honking ..... 35

Table 9. Two-Sample t-test among Three Emotions in Encouraging Seat Belt Use ............................... 36

Table 10. Nontraditional Messages Grouped by Target Behavior and Adjusted Emotion .................... 37

Table 11. Two-Sample t-test among Emotions with New Categorization ............................................. 38

Table 12. List of Nontraditional Messages Used in the Simulation Game ............................................. 41

Table 13. List of Nontraditional Messages Used in the Simulation Game ............................................. 48

1

CHAPTER 1: BACKGROUND

Dynamic message signs have been used for decades to inform drivers about roadway, traffic, or

weather conditions (Shroeder & Demetsky, 2010). Most of the messages used in the past were

standard and impersonal reminders. Recently, transportation agencies across the country, including

Illinois Department of Transportation (IDOT), have started to use nontraditional messages (rhyming,

serious, funny, cultural) for display on dynamic signs. In Illinois, such messages mainly address the

following safety issues: (i) distracted driving (texting, talking on the phone, using apps, eating); (ii)

impaired driving (alcohol, drugs, sleepiness); (iii) occupant restraint (seat belts—both front and back

are required by law, child safety seats); (iv) vulnerable road users (motorcyclists, bicyclists,

pedestrians); and (v) work zone safety. Examples of such messages include “OMG. Are you texting? I

can’t even” and “Slow Down in Work Zones, Give ’em a Brake.” IDOT even promoted a Dynamic

Message Sign Contest in 2018 that encouraged drivers to submit new clever messages that hopefully

can be more effective in making roadways safer (Francis, 2018).

These nontraditional messages are expected to have higher effectiveness in modifying driver

behavior, as they can catch drivers’ attention and provoke an emotional response. Various empirical

studies have shown strong evidence through surveys, mainly based on driver recollection and

reflection, that these messages tend to be more memorable, personal, and more likely to change

behavior (Boyle et al., 2014; Rodier et al., 2010; Schroeder et al., 2016). Quantitative studies that

measured field driver speed in the proximity of a nontraditional message (Haghani et al., 2013;

Harder & Bloomfield, 2008), however, found conflicting results on the effectiveness of even the same

signs—suggesting that some messages could be more effective than others, while certain messages

could be counterproductive (e.g., being distractive) as well. A recent research project at Virginia DOT

(Shealy et al., 2020) offered empirical evidence about the effectiveness of a wide range of

nonstandard messages that target a variety of driver behaviors. Empirical experiments with 300

drivers from Virginia and 80 selected messages (grouped by their target behavior, emotion, and

theme) were conducted. Participants were measured in two ways: (i) answering survey questions on

their perception of the messages, identifying the intent of the messages, and recalling the impacts

and (ii) observing and recording drivers’ neurocognitive response when they read the messages. This

study found that Virginia drivers perceived all types of nontraditional safety messages as effective,

particularly those about distracted driving and seat belt use as well as those provoking a negative

emotion or citing statistics. Yet, it is not clear whether the Virginia findings would also apply to Illinois

drivers.

This project aims to help IDOT determine if nonstandard messages (i) cause a change in driver

behavior and reduce crash frequency in the area of the signage in Illinois, (ii) increase engagement of

the motoring public with safer driving practices, and (iii) have a lasting impact on drivers who see

them (i.e., does the message stick). This project includes a synthesis of current applicable research

and a survey of Illinois drivers. The literature research summarizes the most current and

methodologically sound practice that can be found in published documents. The driver surveys and

online simulation game are developed and carried out with a small group of the targeted

demographic population (university students) to quantify directly the effect and impact of these

messages on Illinois drivers. The results illustrate what type of message (emotionless, negative,

2

humorous) changes driver behavior for increased compliance and decreased crash activity. This

project also generates findings that will serve as guidance on when and where different kinds of

messages may be most effective, providing a long-term benefit to IDOT and partner agencies.

The remainder of this report is organized as follows. Chapter 2 reviews the literature on the effect of

dynamic message signs, empirical study, simulation-based study, and similar practices. Chapter 3

demonstrates the survey and game design. Chapter 4 summarizes collected data from a pilot survey.

Chapter 5 conducts a preliminary analysis on messages with three types of emotions. Chapter 6

concludes and makes recommendations on nontraditional messages.

3

CHAPTER 2: LITERATURE REVIEW

Per guidance of the Technical Review Panel, a literature review and synthesis were conducted to

summarize the current state of practice of using nonstandard messages in Illinois and peer states. It

also documented findings on safety implications of these messages in the literature. The review

primarily includes, but is not limited to, the following items. The first item is a comprehensive list of

all nonstandard messages used in Illinois and peer states to date and a categorical clustering analysis

to group them based on target behavior, theme, and emotion style. The second item is extensive

literature research on empirical studies that observed effectiveness and relationships between the

use of nonstandard messages and the changes in driver behavior and crash occurrence.

A school of empirical studies have been conducted on what and why dynamic messages are more

memorable, personal, and more likely to change drivers’ behaviors. Boyle et al. (2014), for example,

investigated how effective dynamic message signs can modify driver or travel behavior. They

conducted a survey for collecting responses toward message effectiveness in urban areas of four

cities (Chicago, Houston, Orlando, Philadelphia) and concluded that most respondents had a good

understanding of used dynamic message signs. Instead of urban areas, Schroeder et al. (2016)

focused on how dynamic message signs affect driver awareness, understanding, and behavior

changes in rural areas (four corridors in Nevada, Kansas, Missouri, and Minnesota/Wisconsin). Their

study proposed that dynamic message signs were able to act as a useful and effective tool for safety

and public service campaigns.

Some of the related literature has been focused on using simulation or semi-realistic environments to

test drivers’ reactions to dynamic message signs. Huang et al. (2013) investigated the effect of

drivers’ compliance to dynamic message signs through building a highway driving simulator. They

focused on four driver demographics (age, gender, percentage of rural driving, and driving behavior

questionnaire score) and constructed a regression model to estimate drivers’ compliance speed. They

found a dynamic message sign can reduce driving speed by 11%. Strawderman et al. (2013) focused

on how the placement of a work-zone warning sign can affect driver speed compliance. They also

used a driving simulator with 12 driving conditions (three work-zone placement distances × four

warning sign designs) to test participants’ speed change and speed compliance. A video-based

simulation was also conducted to evaluate various dynamic message signs’ impact on highway traffic

(Song et al., 2016). Instead of discussing dynamic message signs’ effectiveness, they suggested that

the presence of dynamic message signs might cause drivers to decelerate on highways and pose

safety hazards. A related questionnaire was used to ask participants for causes and risks associated

with speeding up when drivers are approaching dynamic message signs.

Some research studies measured the effectiveness of dynamic message signs in more realistic

settings. Haghani et al. (2013) investigated dynamic message signs’ impacts on traffic conditions by

installing probe-based sensors and Bluetooth sensors in Maryland. Schroeder et al. (2010) tested

dynamic message signs’ functionality in traffic diversion on I-95 and found that non-traffic-related

messages could be a distraction to drivers and result in unintended queues. Recently, researchers in

Virginia (Shealy et al., 2020) used neurocognition with brain scans to help capture changes to drivers’

attention when they are presented with different dynamic messages. They applied functional near-

4

infrared spectroscopy instruments to collect drivers’ neurocognitive responses and provide physical

evidence of the effectiveness of dynamic messages. They also conducted comparative statistical

analysis to study the effectiveness of different types of dynamic messages.

In summary, both positive and negative aspects of using dynamic message signs, and various types of

nontraditional messages, were reported. In particular, there were a few researchers who mentioned

how drivers’ real-time reactions were affected by dynamic message signs, which has a significant

impact on the messages’ effectiveness. Nevertheless, most of the previous studies on dynamic

messages focused on varying a few specific parameters, such as traffic and speed, instead of

systematically analyzing a wider spectrum of environmental, operational, and human behavioral

factors. In this study, therefore, we develop a new online simulation game and a questionnaire to

collect drivers’ real-time reactions to the presence of nontraditional dynamic messages under a wider

variety of conditions, so that preliminary statistical analysis can be conducted to investigate positive

and negative effects of dynamic message signs.

5

CHAPTER 3: SURVEY/GAME DESIGN

The survey includes two parts: an online simulation game with dynamic message signs and an online

questionnaire. The simulation game is intended to collect participants’ real-time reactions to

different types of dynamic message signs in a semi-realistic environment. The questionnaire collects

demographic and socioeconomic information of participants as well as their understanding,

impression, and acceptance toward different types of dynamic messages. Moreover, after simulation,

the online questionnaire collects participants’ recollection and feedback of messages.

ONLINE GAME DESIGN

The purpose of the online simulation is to (i) develop an online semi-realistic driving environment, (ii)

create an interface between drivers’ behavior and keyboard input, (iii) generate different types of

dynamic messages and random distractions, and (iv) collect and save real-time data, including control

actions and vehicle movements.

The online simulation is developed by Unity Engine (version 2021.3.25f1, https://unity.com), which is

a popular game development engine used to create a 3D simulation environment and provide

convenient downloadable packages. Through Unity Engine, 3D models including vehicles, road

segments, and dynamic message signs can be loaded conveniently onto a server to construct a semi-

realistic immersive virtual environment. Moreover, participants’ mouse and keyboard control as well

as background AI-generated traffic can be coded and embedded in the simulation game.

To host the simulation online, Itch.io (https://itch.io) is selected as the server platform. Its advantages

include providing highly customizable web pages and allowing participants to access the simulation

game directly without any verification or login process. It also generates a URL for easy distribution.

An online website TinyURL (https://tinyurl.com/app) is used to shorten the original URL to a

memorable one for wider distribution.

To gather, process, and record data on the participants’ controls, status, and reactions in the

simulation game, PythonAnywhere (https://www.pythonanywhere.com) is used as a middleware. It is

an online server provider that hosts servers coded in Python. Then, all processed data are sent to

Amazon S3 cloud storage (https://aws.amazon.com/s3), where data are duplicated as backup and are

stored for future retrieval.

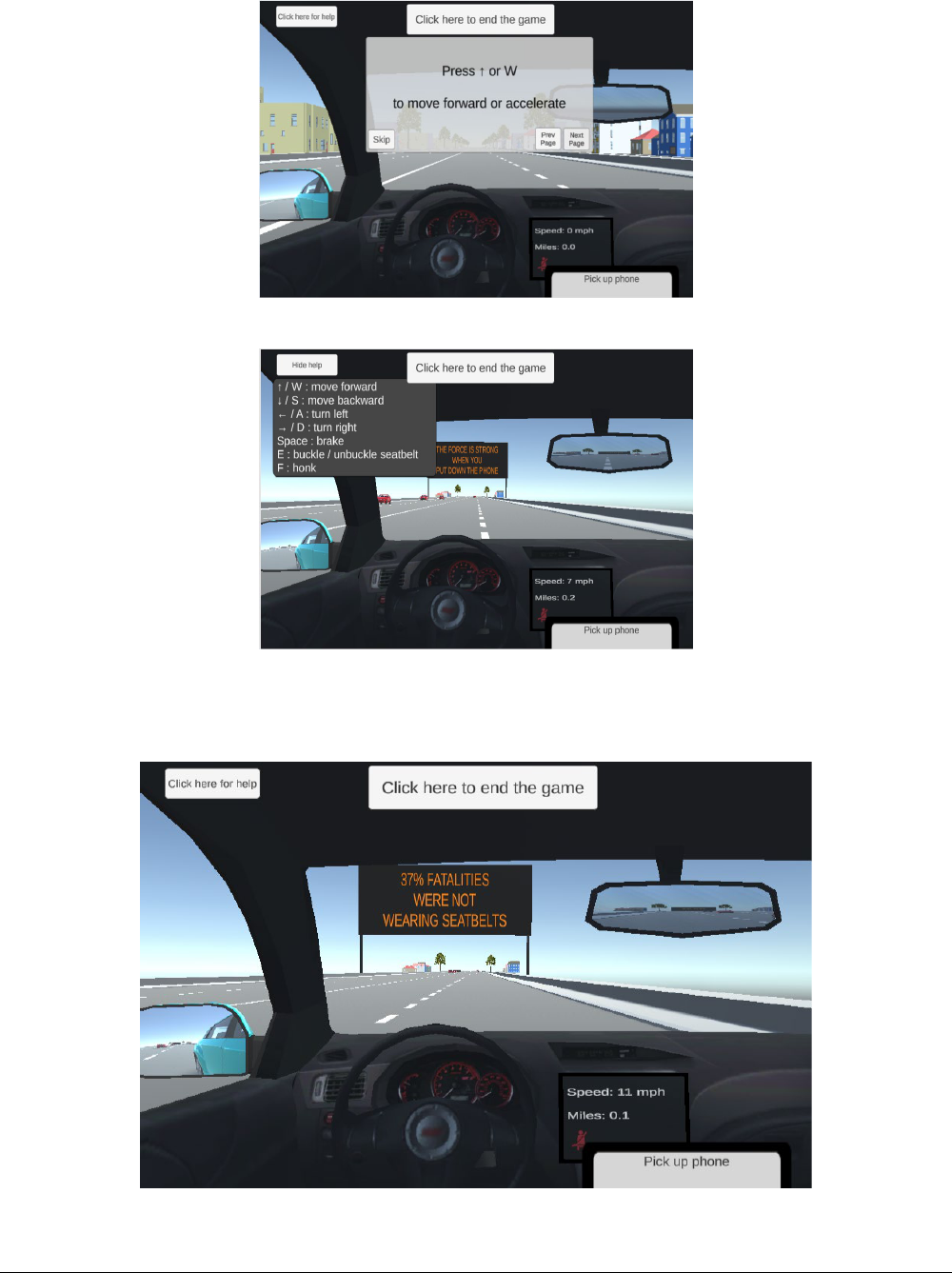

Basic GUI Design

Each participant experiences three stages in the simulation: login, tutorial, and driving. Participants

start the online simulation game via a URL. They see a login interface, as shown in Figure 1.

Participants need to enter an arbitrary ID so the anonymous data collected from the game can be

related to the questionnaire responses. They also need to select an area setting (rural vs urban) for

the game. This page also explains the basic computer system requirements or recommendations

(such as turning on the computer audio for driving noises). Participants are reminded to drive at least

3 miles in the game to qualify to win a gift card.

6

Figure 1. Screenshot. The login page of the simulation game.

Once a participant starts the game, he or she will be seated inside a vehicle on a four-lane freeway in

either a rural or an urban setting (two lanes in each direction). The graphical user interface shows the

vehicles and roadway geometry in 3D visualization, with clear indications of actual driving conditions

(e.g., speed limit and surrounding vehicles). As one will experience in a real vehicle, participants will

be able to observe the front and the rear of the vehicle through the front window, left-side mirror,

and rear-view mirror. The default speed limit is 60 mph, and participants may speed up to 120 mph.

Background traffic is generated automatically by AI based on a certain flow rate of our choice.

A quick tutorial introduces the basic game controls (keyboard definitions) first. Participants can either

read the tutorial one by one or skip it to begin the simulation game directly. A button on the upper-

left corner of the screen (“click here for help”) will provide instructions in case of need. Participants

can use the computer keyboard to accelerate, decelerate, honk at other AI vehicles (to force them to

switch lanes), buckle/unbuckle their seat belt, and change lanes.

There is no fixed end to the game. Participants can end the game at any time by selecting the “click

here to end the game” button on the upper center of the screen. After participants push that button,

they will be directed to a survey questionnaire. (Further details are discussed in the Questionnaire

section.) Data from the simulation game will save automatically and go to PythonAnywhere

middleware and cloud storage as soon as the game ends. Figure 2-a and Figure 2-b show what a

participant sees during the tutorial and driving stages, respectively.

Dynamic messages are shown in orange text on a black digital board outside the vehicle. The font size

is larger than the font on signs in reality for clearer visibility. Figure 3 presents a sample board. These

message signs are generated every 0.5 miles, and the content in the sign is drawn automatically from

preset choices, as discussed in the Dynamic Messages section. There are 815 dynamic message signs

uniformly generated in the simulation.

7

(a) Tutorial interface

(b) Driving interface

Figure 2. Screenshot. Basic GUI design for the online simulation game.

Figure 3. Screenshot. Nontraditional messages shown on a dynamic message sign.

8

Participants also see a simple front panel that displays real-time driving status, including the current

speed, total distance traveled, seat belt use status, and crash status. The speed will display in white if

it is at or under the speed limit. It will turn red and blink three times if the participant is over the

speed limit. The same occurs for the seat belt status. The panel will display a red unbuckled logo if the

participant is not buckled up. Participants are unbuckled by default (at the beginning of the game),

and this is intended to test their seat belt use habit. Last, whenever a participant hits another car in

the simulation game, a crash logo will cover the whole panel and last for three seconds. Figure 4-a,

Figure 4-b, and Figure 4-c compare panels with and without these alarms.

(a) No alarm

(b) Speed alarm

(c) Crash alarm

Figure 4. Screenshot. Panels with and without alarms in the online simulation game.

Additionally, the simulation provides a simple phone interface, which allows participants to play

music, check emails/text messages, and answer calls. Participants can either show or hide the phone

interface at any time while driving. When the phone interface is activated, as shown in Figure 5-a, the

driver’s vision is partially blocked, mimicking real-world eyesight distractions. Figure 5-b shows five

possible phone interfaces at different stages of use. The first interface displays four possible

application icons, which indicates that the phone is not in active use. Users can access different

functionalities: music (upper left), texting (upper right), text messages (lower left), and phone calls

(lower right). If the participant clicks on the music icon, he or she can further choose one of three

types of music genres. If the participant clicks on the text messaging, email, or call icon, a

corresponding dialog box will pop up. In the simulation game, emails and phone call events are

automatically generated approximately every 40 and 80 seconds, respectively, to distract participants

9

and observe their behavior while distracted. Participants will hear alert sounds from the phone when

such an event occurs but can either ignore or respond to the pop-up messages or phone calls. Phone

call alerts automatically end after 10 seconds if participants do not interact with the phone interface.

(a) Activated phone interface

(b) Five possible interfaces for accessing music, texting, email, and phone calls

Figure 5. Screenshot. Phone interfaces in the simulation game.

Dynamic Messages

The main purpose of this game is to check which type(s) of dynamic messages are effective in

changing driver behavior for increased compliance and decreased crash activity. As such, over 80

nontraditional messages are gathered and sorted into 15 categories based on the literature review

(Shealy et al., 2020). Each nontraditional message is categorized by target behavior and emotion.

There are five target behaviors (general safe driving, driving without a seat belt, distracted driving,

impaired and drowsy driving, and general aggressive driving) and three emotions (emotionless,

humorous, and negative). Table 1 lists the different types of nontraditional dynamic messages, their

relative frequency of use in the simulation games, and some representative examples. Appendix A

presents the complete list of messages used in the game.

10

Table 1. Nontraditional Messages Grouped by Target Behavior and Emotion

Index

Behavior

Emotion

Frequency

of use (%)

Representative example

1

General safe

driving

Emotionless

7.12

DRIVING SAFELY?

I LIKE IT

I LOVE IT

2

General safe

driving

Humorous

4.66

SANTA’S COMING

HAVE YOU BEEN A GOOD DRIVER?

3

General safe

driving

Negative

6.01

757 FATALITIES SONS, DAUGHTERS

STOP THE HEARTACHE

4

Driving

without a seat

belt

Emotionless

5.52

SEE YOUR BFF TONIGHT

BUCKLE UP

5

Driving

without a seat

belt

Humorous

6.99

DUCK,

DUCK,

BUCKLE UP

6

Driving

without a seat

belt

Negative

6.87

72 WERE UNBUCKLED

7

Distracted

driving

Emotionless

5.64

PLAY BALL!

STRIKE THE

DISTRACTIONS

8

Distracted

driving

Humorous

11.53

AVOID AN APPSIDENT

PHONES DOWN

9

Distracted

driving

Negative

7.12

NO TEXT

IS WORTH

A LIFE

10

Impaired and

drowsy

driving

Emotionless

5.64

BE ALERT

ARRIVE UNHURT

11

Index

Behavior

Emotion

Frequency

of use (%)

Representative example

11

Impaired and

drowsy

driving

Humorous

6.38

DON’T BE TRICKED

DUIS ARE NO TREAT

12

Impaired and

drowsy

driving

Negative

7.12

BLOWING .08

IS LIKE

BLOWING $10,000

13

General

aggressive

driving

Emotionless

6.38

SPEEDING IS

UNSPORTSMANLIKE

CONDUCT

14

General

aggressive

driving

Humorous

4.91

IT’S OK

TO BE A

SLOW POKE

15

General

aggressive

driving

Negative

8.10

DO NOT TELL

A LIE

OBEY THE LIMIT

QUESTIONNAIRE

The purpose of the online questionnaire is to (i) investigate drivers’ demographic and socioeconomic

information, (ii) collect their opinion toward nontraditional dynamic messages, and (iii) accurately

capture the effectiveness of dynamic messages on impacting drivers’ behaviors. A total of 23

questions are presented to each participant via Google Forms. Among the 23 questions, one asks for

the ID used in the online simulation (to establish connection while remaining anonymous), four are

related to participants’ opinions toward nontraditional messages, eight are related to their

demographic and socioeconomic background, and 10 are related to their perception of driving

experience and acceptable driving behaviors. Neither personal information nor any forms of

identification were collected from the respondents. All questions and their corresponding intentions

are listed in Table 2.

12

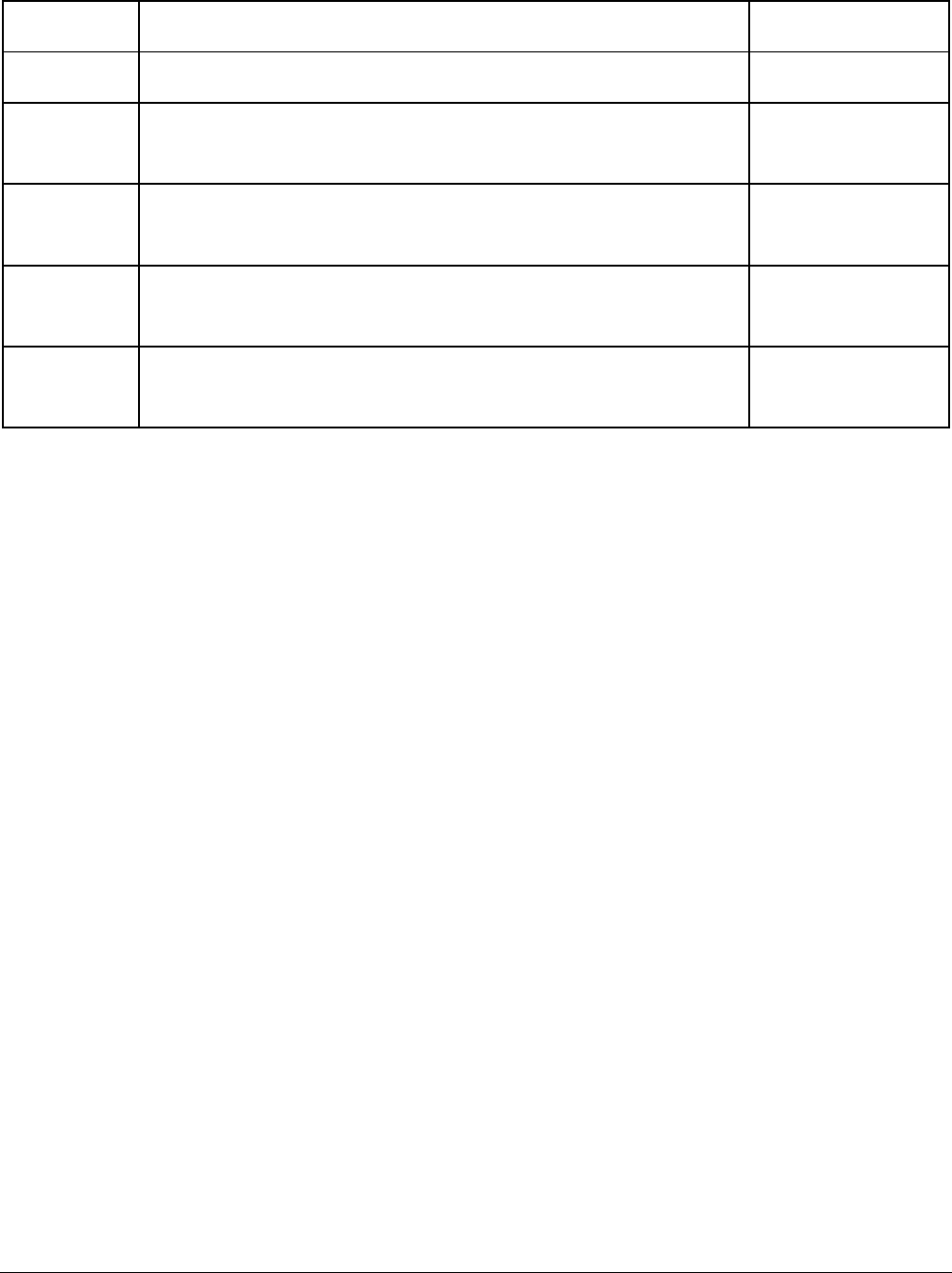

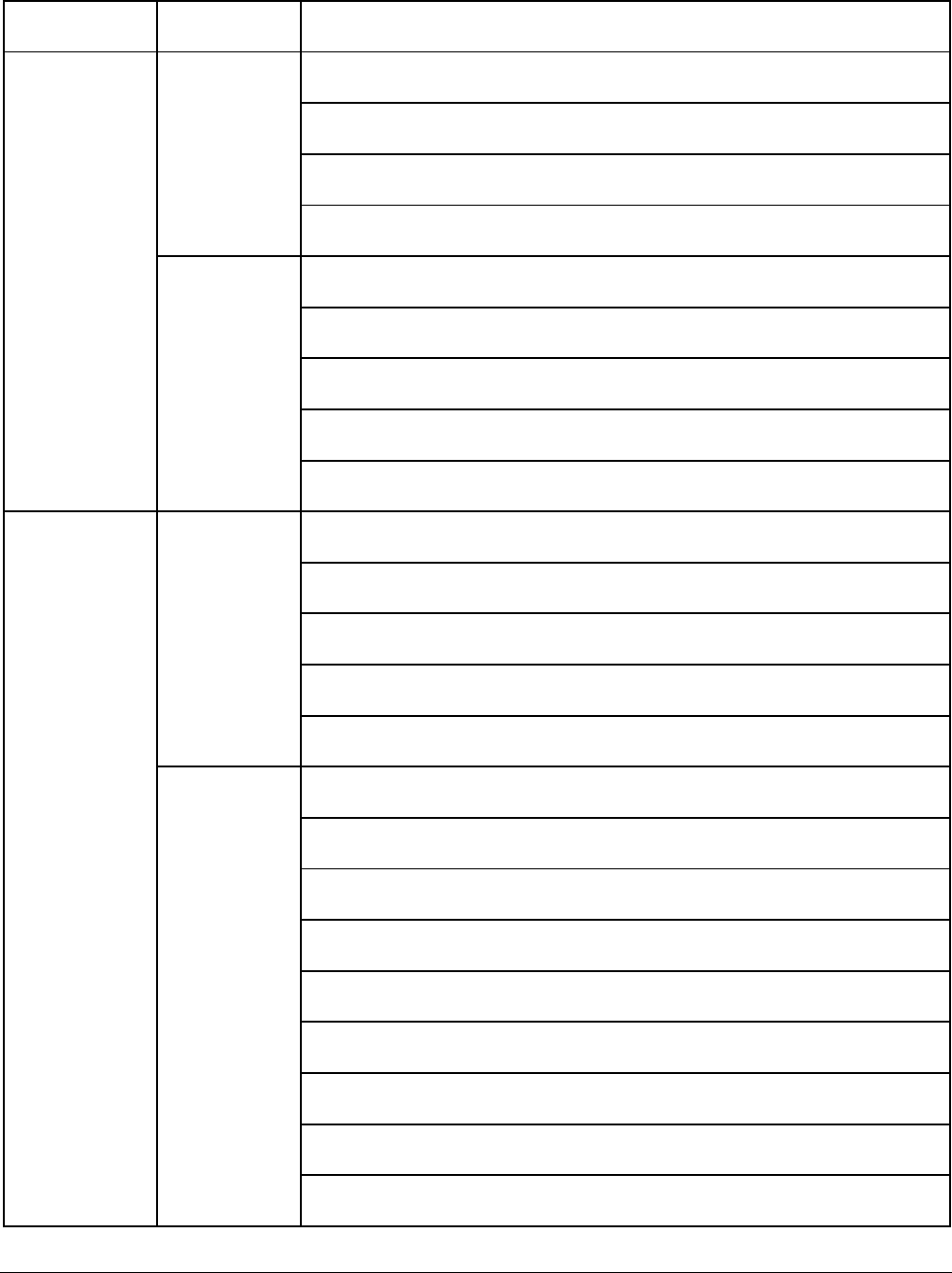

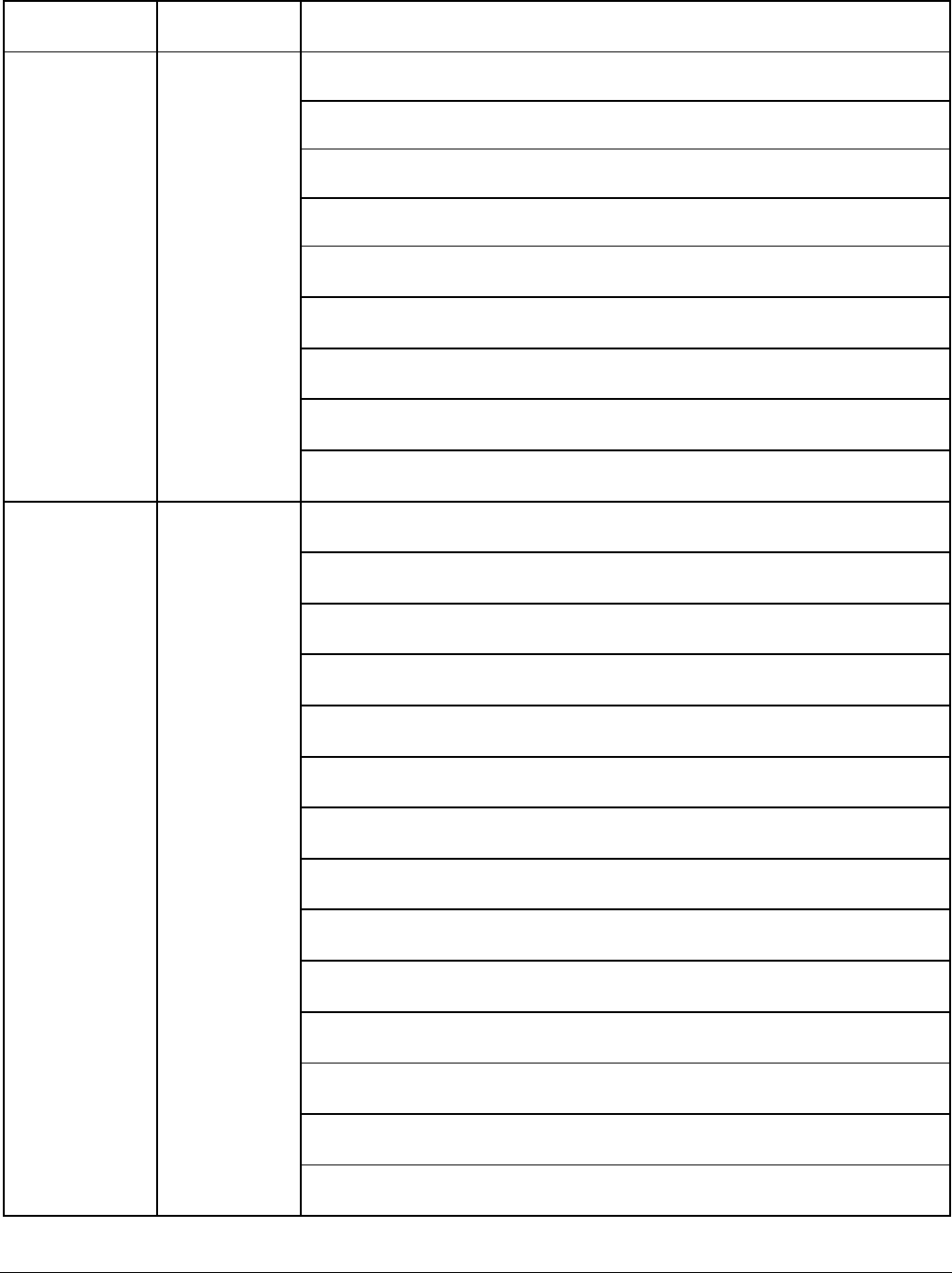

Table 2. Online Questionnaire Questions and Corresponding Categories

Question #

Question

Intention

1

Please enter the same ID you used in the driving game.

Logistics

2

Among all the messages you saw today, which one(s) were the

most memorable and why?

Message Opinions

3

Do you think that any of the messages today were

inappropriate? If yes, which ones?

Message Opinions

4

Which type of behavior do you think those message(s) were

intended to address (select all that apply)?

Message Opinions

5

Given the following list of driving behavior, rank the

importance of changing the behavior: not wearing seat belts,

speeding, texting and driving, drinking and driving, and drowsy

driving. (1=lowest, 5=highest)

Message Opinions

6

What is your gender?

Demographic

7

What is your marital status?

Demographic

8

Which college are you in?

Demographic

9

Which of the following best describes your academic status?

Demographic

10

What type of area do you live in?

Socioeconomic

11

On which type of roads do you drive the most?

Socioeconomic

12

Do you own a car?

Socioeconomic

13

Have you been involved in accidents during the past 5 years?

Socioeconomic

14

How often do you listen to music or radio during driving?

Driving Behaviors

15

How often do you send text messages during driving?

Driving Behaviors

16

How often do you call others during driving?

Driving Behaviors

17

How often do you honk at others during driving?

Driving Behaviors

18

How often do you buckle up during driving?

Driving Behaviors

13

Question #

Question

Intention

19

How often do you change lanes frequently during driving?

Driving Behaviors

20

How often do you overtake if trapped behind a slow-moving

vehicle?

Driving Behaviors

21

If the speed limit is 25 mph, how fast do you consider as an

acceptable speed?

Driving Behaviors

22

If the speed limit is 55 mph, how fast do you consider as an

acceptable speed?

Driving Behaviors

23

If the speed limit is 70 mph, how fast do you consider as an

acceptable speed?

Driving Behaviors

14

CHAPTER 4: PILOT SURVEY RESULTS

A small-scale deployment of the game/survey was conducted on February 16–26, 2024. Both physical

and electronic flyers were distributed to 350 graduate students and 400 undergraduate students in

the Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering at the University of Illinois Urbana-

Champaign. A total of 118 responses were received by February 26, 2024, among which 80 finished at

least 3 miles of driving in the online simulation game, and 66 of them also completed the online

questionnaire. The remainder of this chapter summarizes the collected data.

ONLINE SIMULATION GAME RESULTS

The online simulation tracks each participant’s keyboard control records and the corresponding

vehicle movements every second and saves them for later statistical analysis. Recorded real-time

control data include, but are not limited to, (i) speed and location profiles; (ii) crash records, (iii)

participants’ seat belt status, (iv) participants’ reactions to phone messages and/or phone calls, (v)

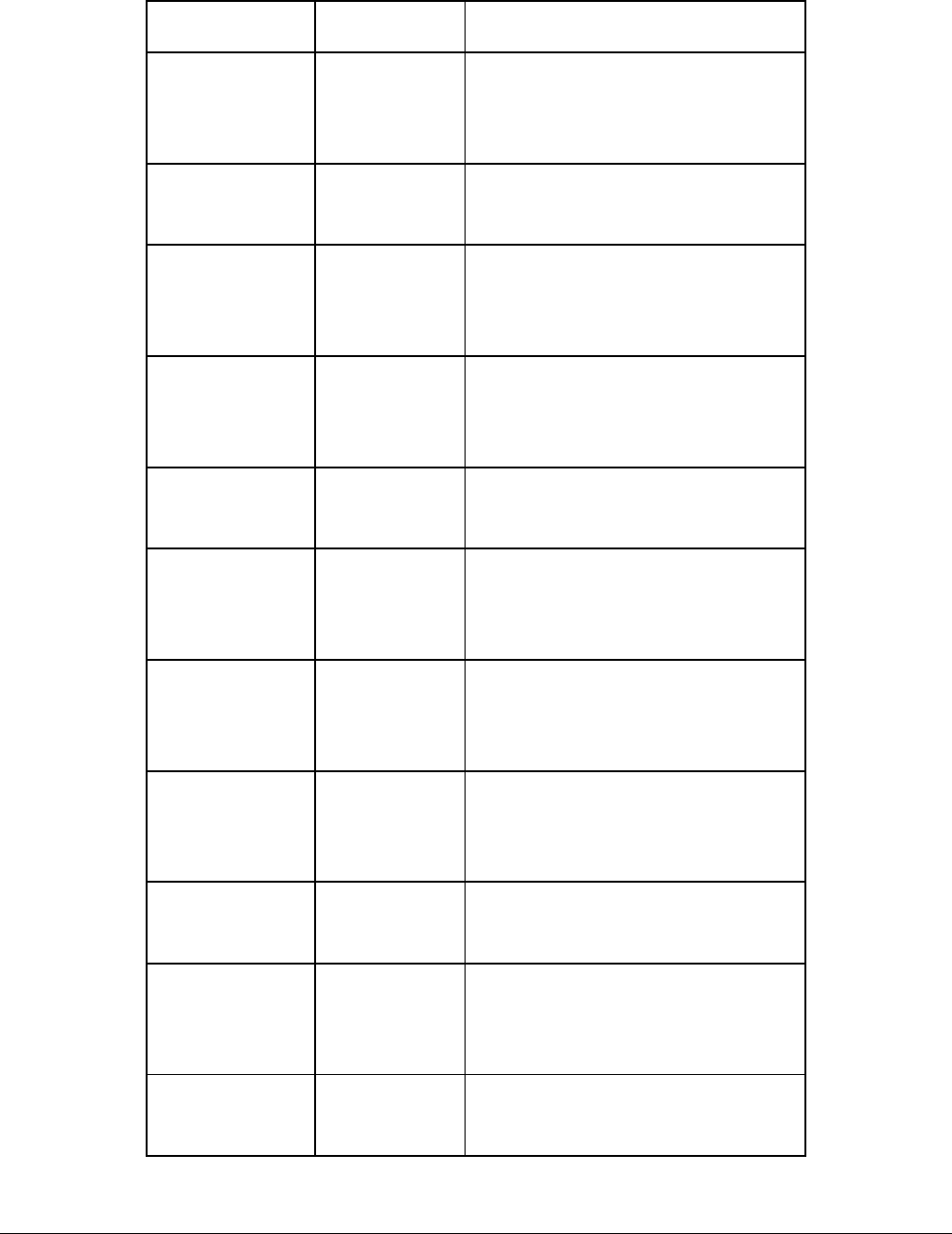

participants’ lane changing controls, and (vi) participants’ honk actions. Table 3 and Figure 6-a to

Figure 6-f show an example of real-time recorded data from the same participant in the simulation

game. Table 3 lists all nontraditional messages seen by the participant as well as the corresponding

times at which they passed those signs. For example, at the 159th second, the participant saw the

message “DESIGNATED DRIVERS MAKE THE BEST NEW YEAR’S DATES,” which reminded the

participant to drive safely. Figure 6-a shows a participant’s driving speed record every second. This

participant obeyed the speed limit for the first half of the journey, while accelerating from 60 mph to

the maximum speed of 120 mph at about the 250th second. Figure 6-b shows the participant’s bird-

eye-view driving trajectory, where the x- and y-axis represent the longitudinal and lateral locations

with respect to the starting point. It also directly captures the participant’s lane changing actions. The

figure shows that this participant frequently changed lanes initially within the first mile, but then

drove stably in the remaining 3.2 miles of travel. Figure 6-c records the participant’s reaction to

incoming phone calls. Every time a text message pops up or a phone call comes (with audio and visual

prompts), a participant’s behavior toward these distractions is represented by his or her interactions

with the phone interface. This participant received phone calls at seconds 80, 160, 240, and 320, but

only picked up those at the 160th and 320th seconds. Figure 6-d and Figure 6-e show whether the

participant hit other cars or honked at other cars while driving, which is an important indicator of

aggressiveness. In both diagrams, honking and two crashes happened around the 320th and 330th

seconds. Recall that these crash times overlap with active phone usage near the 320th second, while

the vehicle is traveling at 120 mph, which indicates strong safety hazards imposed by phone use at

high speeds. Figure 6-f shows the participant’s seat belt buckled/unbuckled status while driving. The

participant started to buckle up only at the 260th second, soon after he or she saw two messages

related to seat belt usage: “60% OF TEEN ROAD DEATHS IN VIRGINIA ARE UNBUCKLED” and

“PROTECT YOURSELF BUCKLE UP,” which were displayed to him or her at the 235th and 249th

seconds. This observation indicates that dynamic messages do seem to have notable impacts on

drivers’ behavior on seat belt use.

15

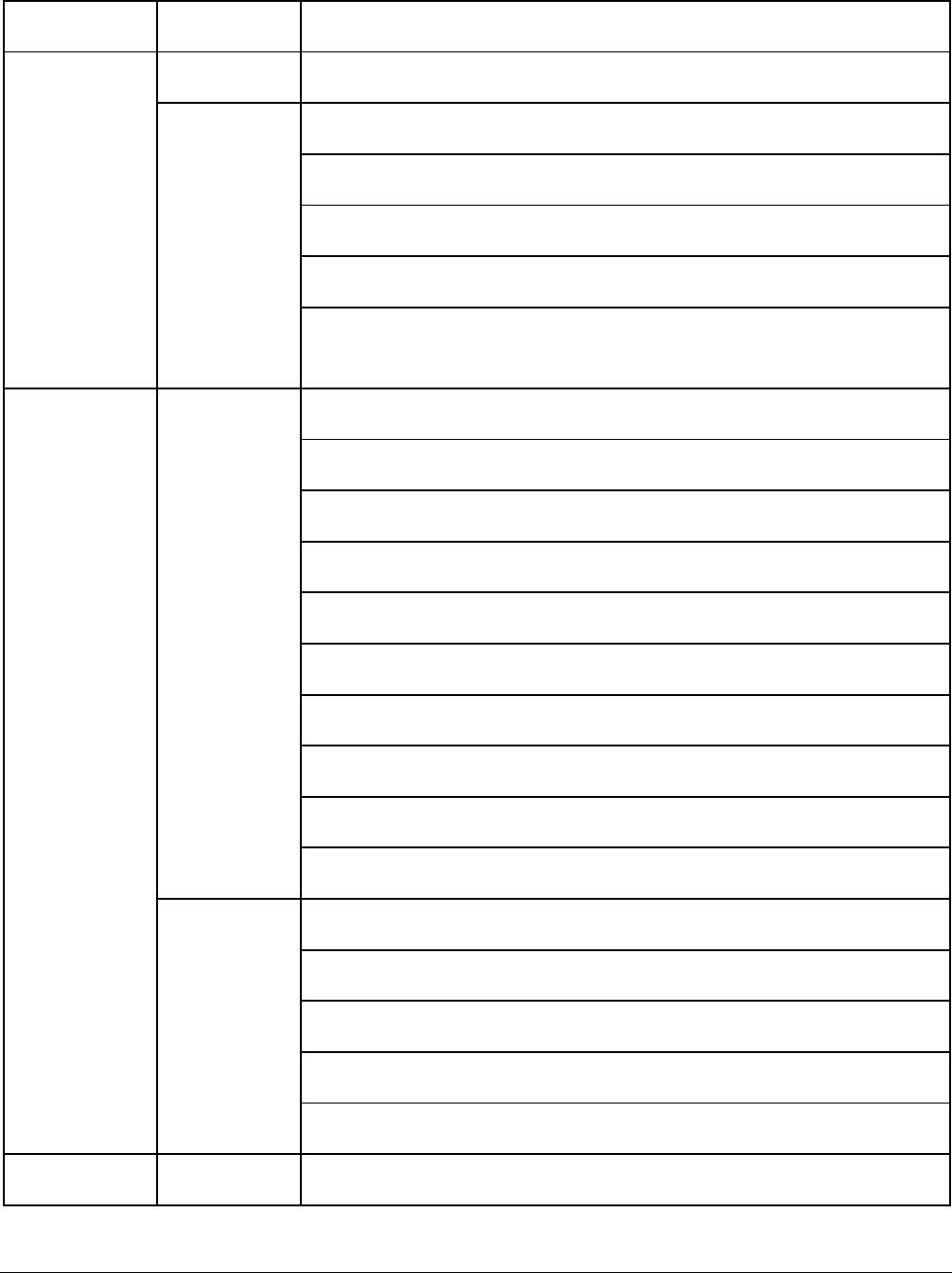

Table 3. Sample Record of Shown Nontraditional Messages from One Simulation Game

Index

Time (sec)

Nontraditional messages

0

16th

BE ON SANTA'S

NICE LIST

DRIVE POLITELY

1

77th

YOU HAD ME AT

I DON’T TEXT AND DRIVE!

2

105th

DESIGNATED DRIVERS

MAKE THE BEST

NEW YEAR’S DATES

3

132nd

60% OF TEEN ROAD DEATHS

IN VIRGINIA

ARE UNBUCKLED

4

159th

9 OF 17 FATALITIES

UNBUCKLED THIS YEAR

5

186th

MOM NEEDS

YOUR HUG NOT

YOUR TEXT

6

214th

MOM NEEDS

YOUR HUG NOT

YOUR TEXT

7

235th

60% OF TEEN ROAD DEATHS

IN VIRGINIA

ARE UNBUCKLED

8

249th

PROTECT YOURSELF

BUCKLE UP

9

263rd

EDDIE SAYS

DON’T TEXT & DRIVE

THE TWITTERS FULL

10

277th

LIFE IS A HIGHWAY

DRIVE SAFELY ALL DAY LONG

16

Index

Time (sec)

Nontraditional messages

11

291st

TEXTING & DRIVING

IS CLEVER

SAID NO ONE EVER

12

305th

TEXTING WHILE DRIVING?

OH CELL NO.

(a) Speed profile

(b) Vehicle lateral location

17

(c) Phone use status

(d) Crash status

(e) Honk actions

18

(f) Seat belt use status

Figure 6. Graph. Sample data records from the same participant.

All participants’ simulation data are sent to online cloud storage. In this way, an individual

participant’s data can be organized by attributes and merged with dynamic message data to enable

statistical behavior analysis. Figure 7-a to Figure 7-f are histograms of all collected participant data (a

total of 118 games, including those who did not drive more than 3 miles). Figure 7-a presents the

average speed histogram, which has a mode of 25–30 mph and an average of 43 mph. The speed

distribution is nearly normal, but there is a non-negligible portion of extreme speeds. Figure 7-b

shows the histogram of phone interactions. The phone interaction number has a mode of 0–2 times

and a mean of 11.8 times. Figure 7-c shows a histogram of the number of times participants honked

at other cars. Interestingly, only a few participants honked, but those who did, honked a lot—

indicating strongly opposite behavior among participants. The mode of the honking number is 0

times, and the mean is shockingly 20.2 times. Figure 7-d shows a histogram of the crash number.

Nearly half of the respondents experienced at least one crash. The mode of the crash number is 0

times, and the mean is 1.18 times. Figure 7-e presents a histogram of the time it takes participants to

buckle up their seat belts for the first time. Over 62% of participants who buckled up in the game (or

43 out of 74) buckled up their seat belts as they started to drive; 44 participants never buckled up

throughout the simulation game. Figure 7-f shows a histogram of the distance traveled by

participants. The mode of traveling distance is 3 miles and the mean is 3.43 miles. In summary, most

participants drove within the speed limit and rarely made aggressive actions, while, on the other

hand, we observed a small number of extremely aggressive behaviors as well.

19

(a) Average speed

(b) Phone use number

(c) Honk number

20

(d) Crash number

(e) Time to buckle seatbelt

(f) Travel distance

Figure 7. Graph. Histograms of attributes among 118 participants.

21

QUESTIONNAIRE DATA

A total of 66 valid responses were collected from the questionnaire, and they are classified into four

main categories: demographic information, socioeconomic information, driving experience and

behavior perception, and opinions toward nontraditional messages. Histograms and pie graphs are

plotted to show a clear view of these responses.

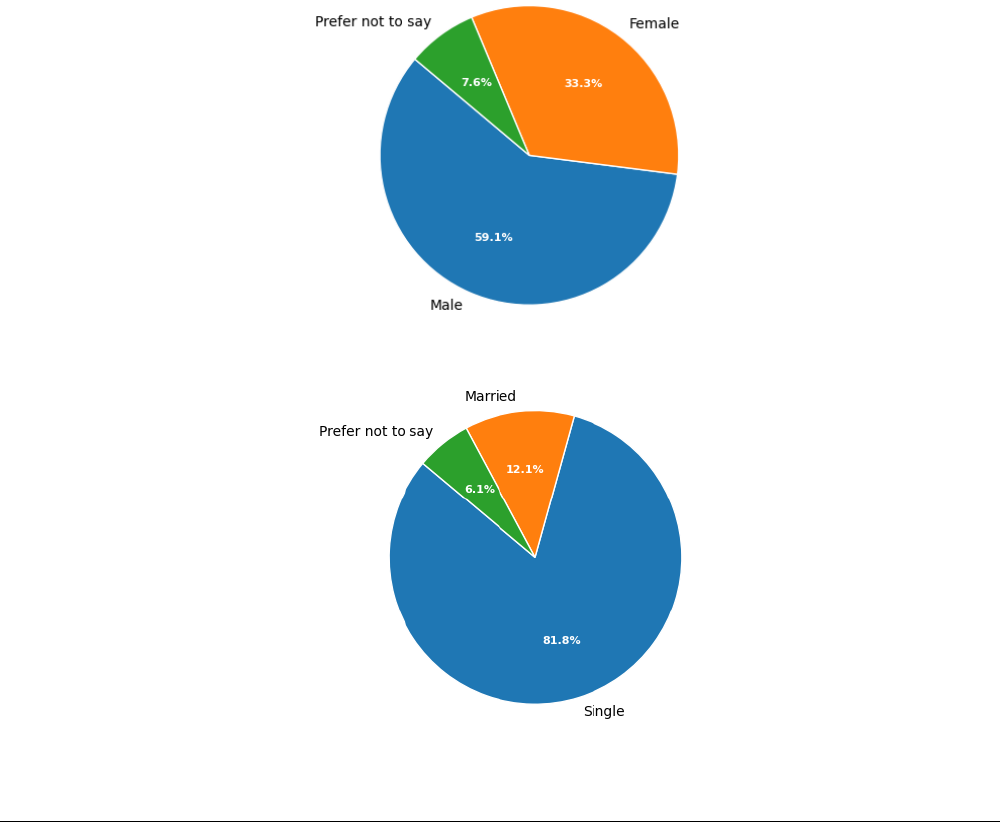

Demographic Information

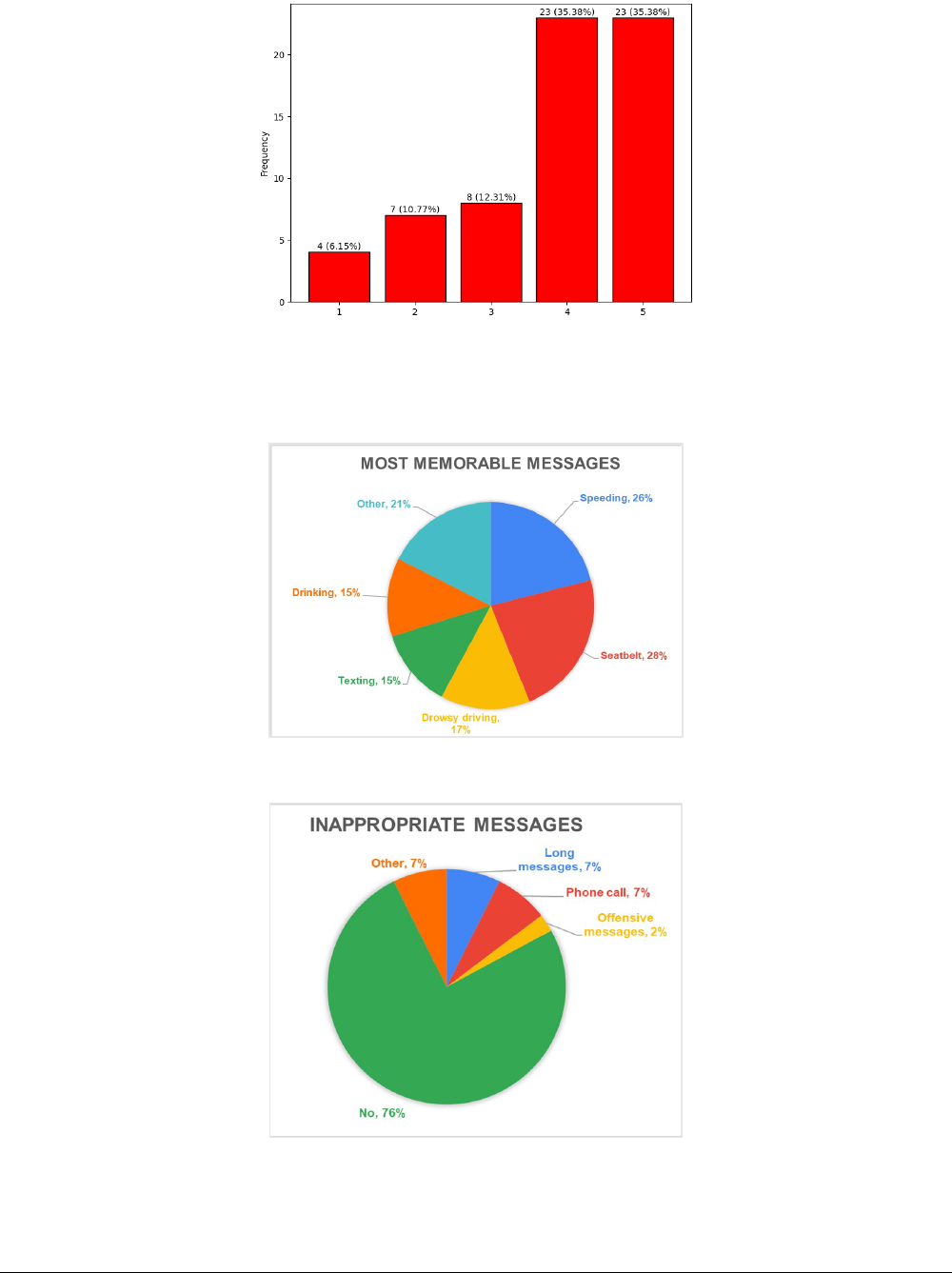

Figure 8-a to Figure 8-d plot pie graphs of participants’ demographic information. Figure 8-a is the

gender pie graph, which shows that the whole surveyed group is composed of at least 59.1% males

and 33.3% females. These percentages largely match the demographic profile of students in UIUC’s

civil engineering department—indicating that males and females are largely equal in willingness to

participate in the game/survey. Figure 8-b shows the marital status, indicating that 81.8% of the

participants are single and 12.1% are married. Figure 8-c shows that most but not all (90%)

participants are from the engineering college—indicating some participants from other colleges were

invited by civil engineering students. Figure 8-d shows the distribution of their academic standing,

where an approximately equal share of respondents are undergraduate, master’s, and PhD students.

(a) Gender

(b) Marital status

22

(c) College status

(d) Academic status

Figure 8. Graph. Demographic information of respondents.

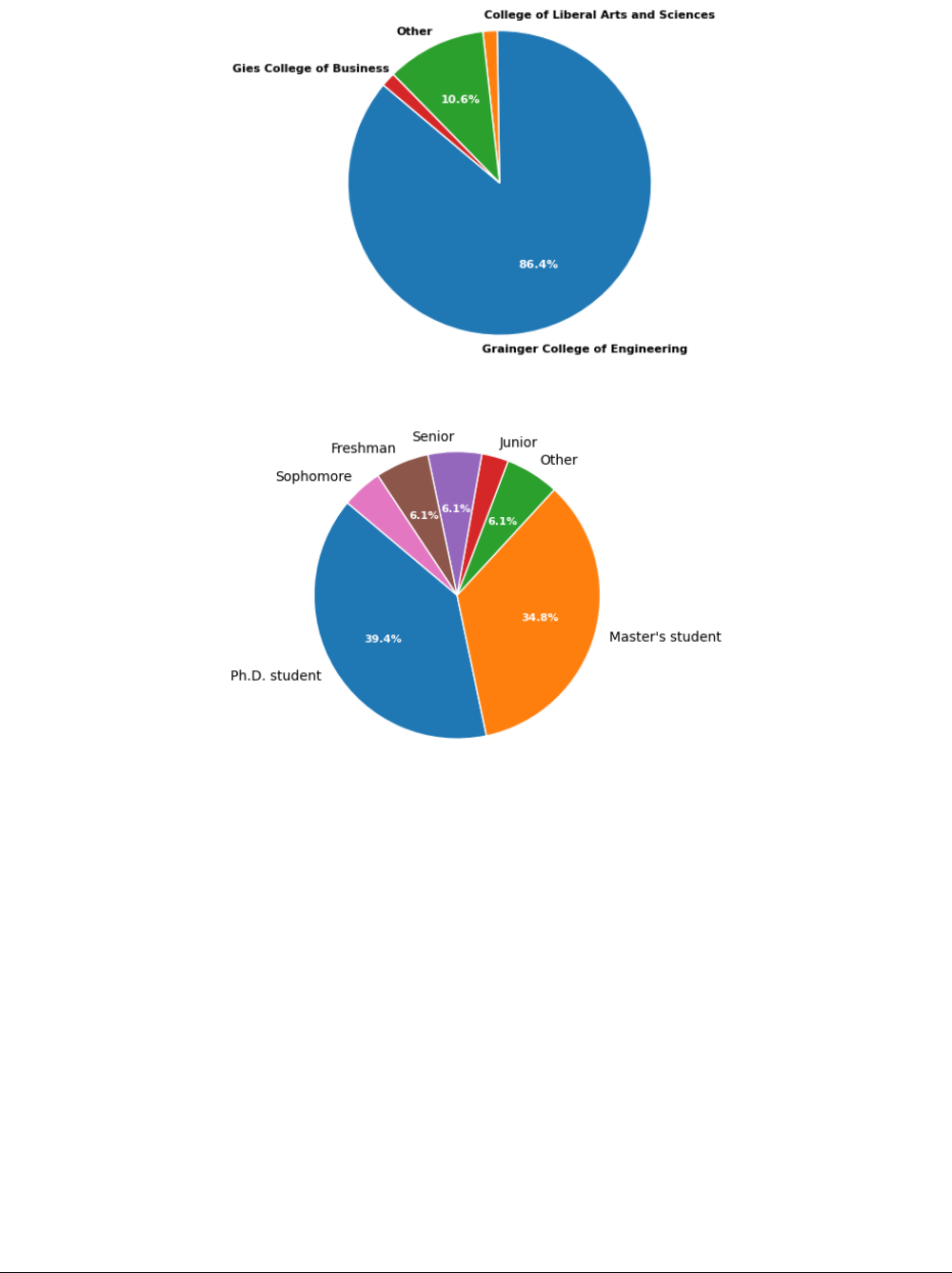

Socioeconomic Information

Figure 9-a to Figure 9-d plot pie graphs of the participants’ socioeconomic information. Figure 9-a

shows the participants’ living area; nearly half of them live in suburban areas and half in urban areas.

Figure 9-b indicates the driving experience with roadway types. The most driven road type is

municipal streets (33.3%), and the least driven road type is interstate freeway (7.6%). Figure 9-c

shows that only half of the participants have a car and/or possess legal driving ability. Figure 9-d

presents responses to the question of whether an accident happened in the past 5 years, and 13.6%

participants responded “yes” to this question.

23

(a) Living area

(b) Most driven road type

(c) Car ownership

24

(d) Involved in an accident in past 5 years

Figure 9. Graph. Socioeconomic information of respondents.

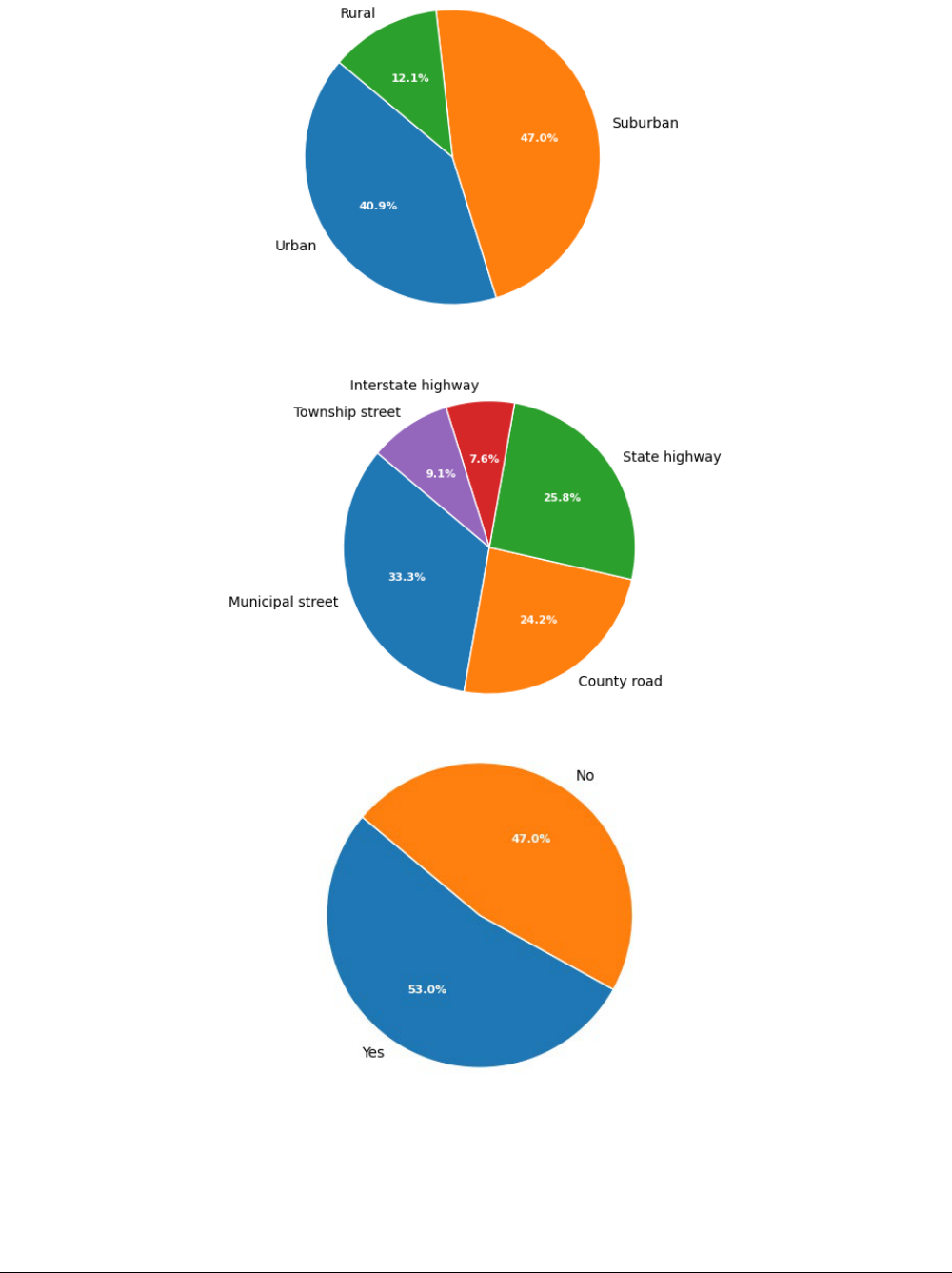

Driving Behavior Information

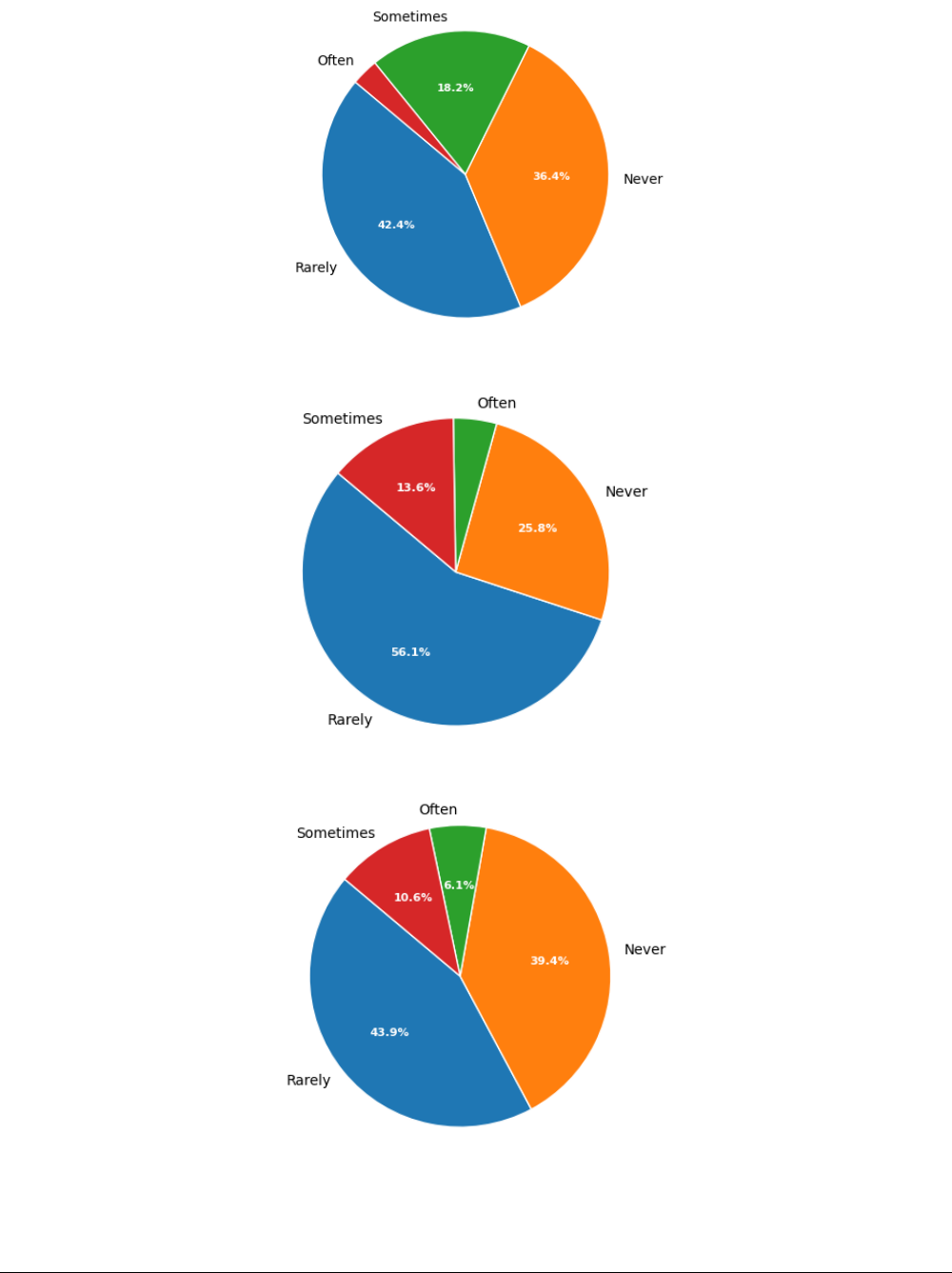

Figure 10-a to Figure 10-d plot pie graphs of participants’ stated driving behavior. Each pie graph is

related to a typical behavior that may cause distracted driving. Figure 10-a shows that 77.3% of

participants often listen to music when driving. Figure 10-b shows that 36.4% of participants never

send text messages when driving, while at least 18.2% of them do sometimes or often send text

messages. Similarly for phone calls and honking, most participants responded “never” or “rarely” for

phone calling, but there was still a small portion (18.1% and 16.7%) that selected “sometimes” or

“often,” as shown in Figure 10-c and Figure 10-d, respectively. In general, when driving, most people

listen to music, rarely send text messages, rarely call others, and rarely honk at others.

(a) Listening to music

25

(b) Sending text messages

(c) Phone calling

(d) Honking at others

Figure 10. Graph. Driving behaviors information of respondents.

26

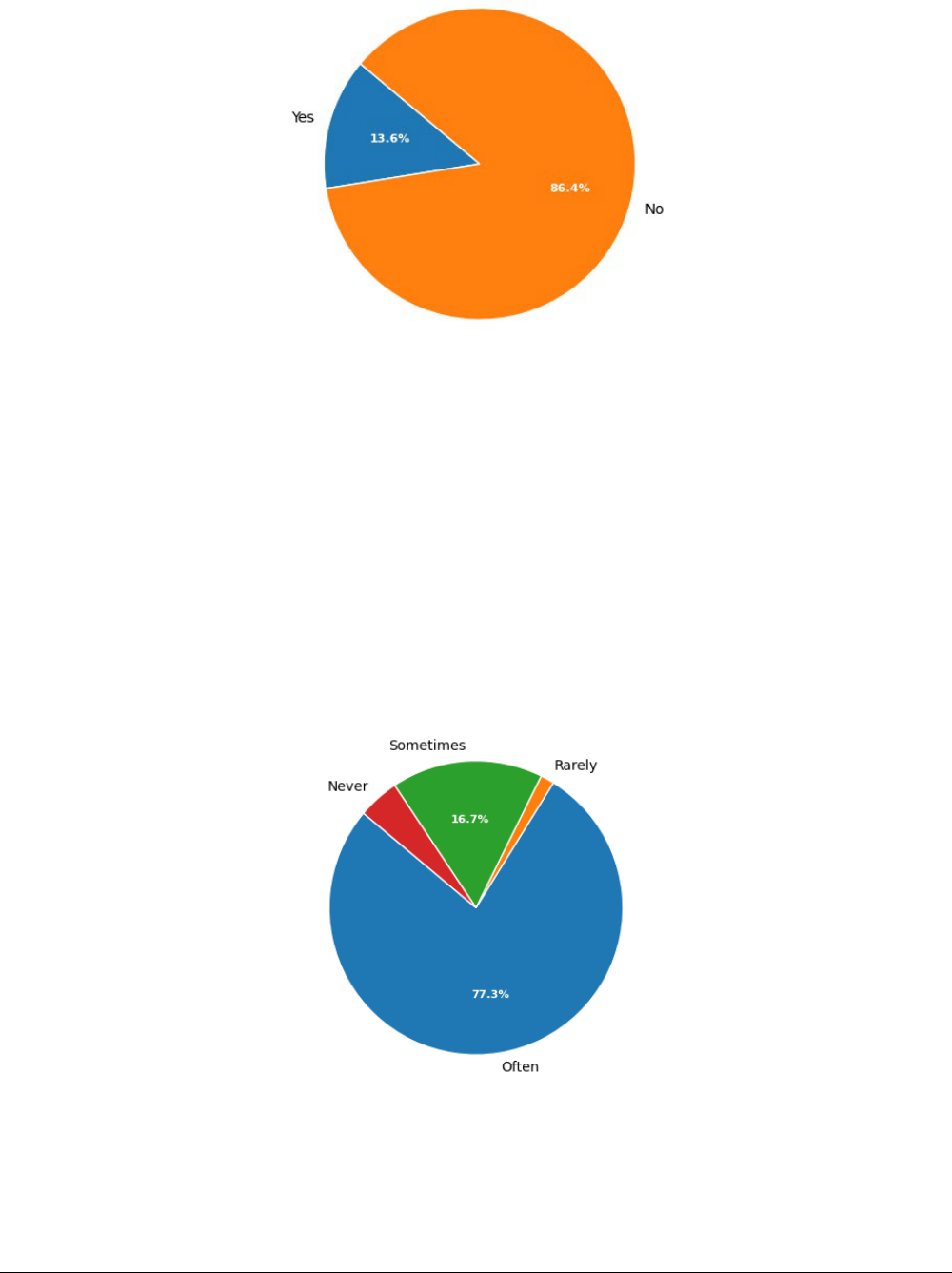

Impression on Nontraditional Messages

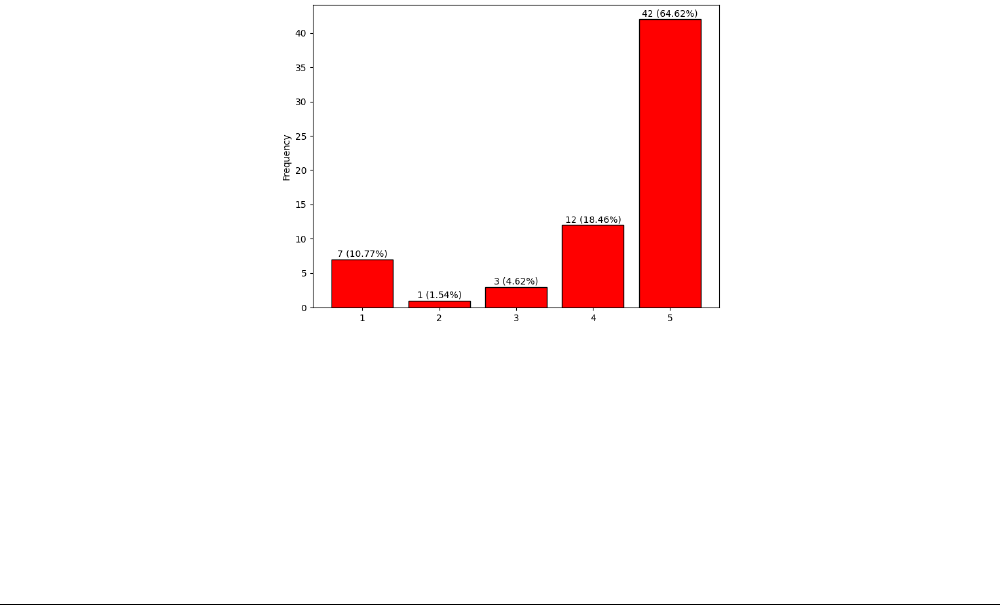

The questionnaire collected participants’ opinions toward nontraditional messages through ranking

the importance of different types of messages. The more people ranked a specific message higher,

the more important and more sensitive such a message is to the safe driving behavior of the public.

Figure 11-a to Figure 11-e show participants’ ranking of the importance of nontraditional messages

on changing a typical driving behavior. In sequence, Figure 11-a to Figure 11-e focus on messages’

importance to not wearing seat belts, speeding, texting and driving, drinking and driving, and drowsy

driving. We can compare the proportions of people ranking each target behavior as 1 (lowest) and 5

(highest). It is observed that 66.7% of participants rank speeding as 5, while 10.6% of participants

rank not wearing seat belts as 1. This indicates that most participants regard speeding as the most

important and dangerous behavior and not wearing seat belts as the least important and negligible

behavior.

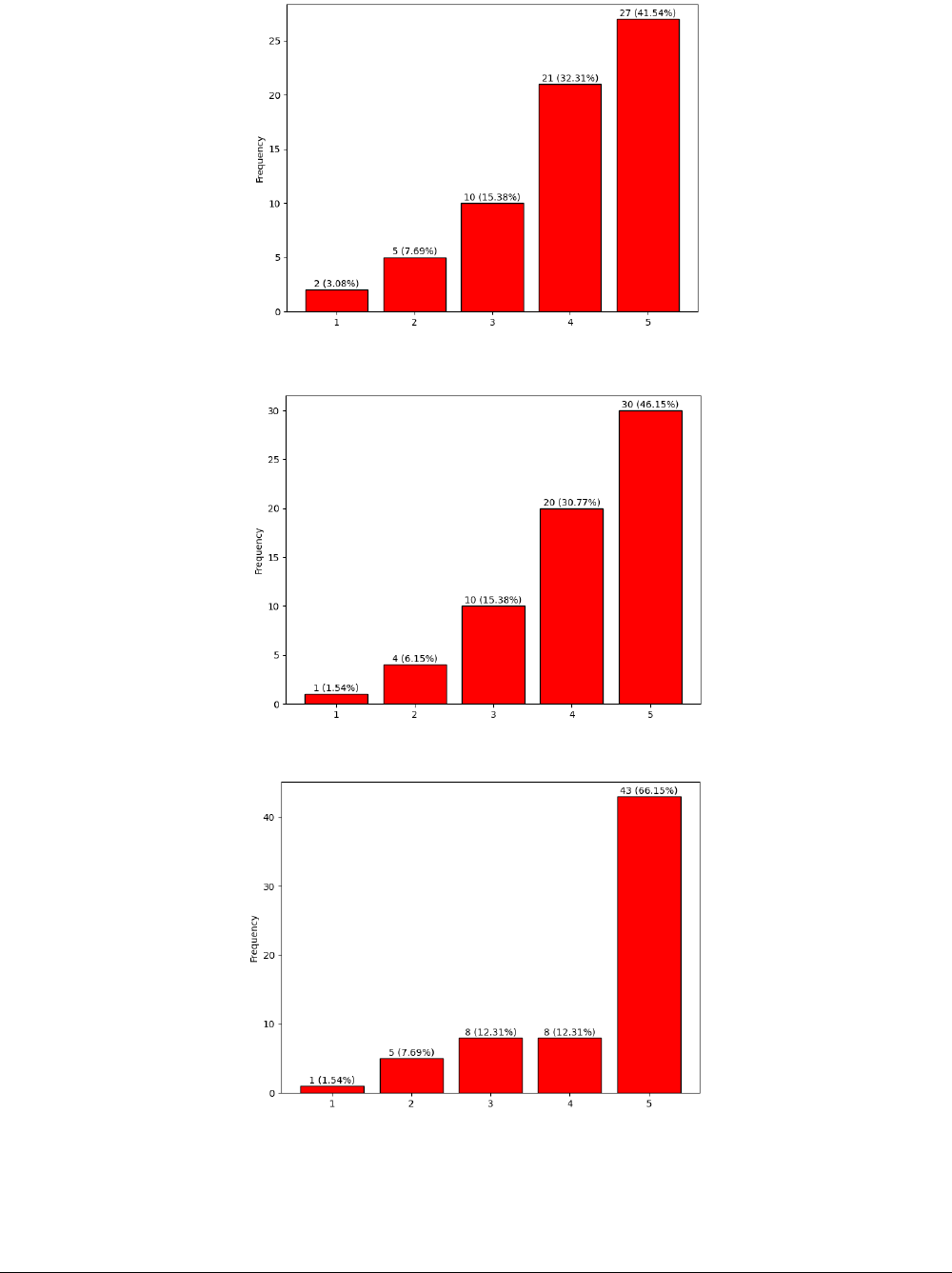

Participants were also asked to recall the most memorable and inappropriate messages they saw

during the online simulation. Among the 66 questionnaire responses, 57 mentioned at least one most

memorable message and 47 responded at least one inappropriate message. Figure 12-a to Figure 12-

b present the composition of most memorable message types and inappropriate messages. Messages

related to seat belts (28%) and speeding (26%) are the two most memorable message types. Among

all responses to inappropriate messages, most people (76%) answered “no” recollection of such types

of messages. A few participants answered that those related to long dynamic messages and phone

calls were distracting for driving. Only 2% of participants gave specific messages that were considered

offensive, which suggested that including a specific culture as part of the message (e.g., “Luck of the

Irish won’t help if you drive drunk”) might not be appropriate. Some top responses to these two

questions are listed in Table 4.

(a) Not wearing seat belts

27

(b) Speeding

(c) Texting and driving

(d) Drinking and driving

28

(e) Drowsy driving

Figure 11. Graph. Opinions toward nontraditional messages in the questionnaire.

(a) Most memorable messages

(b) Inappropriate messages

Figure 12. Graph. Most memorable and inappropriate messages.

29

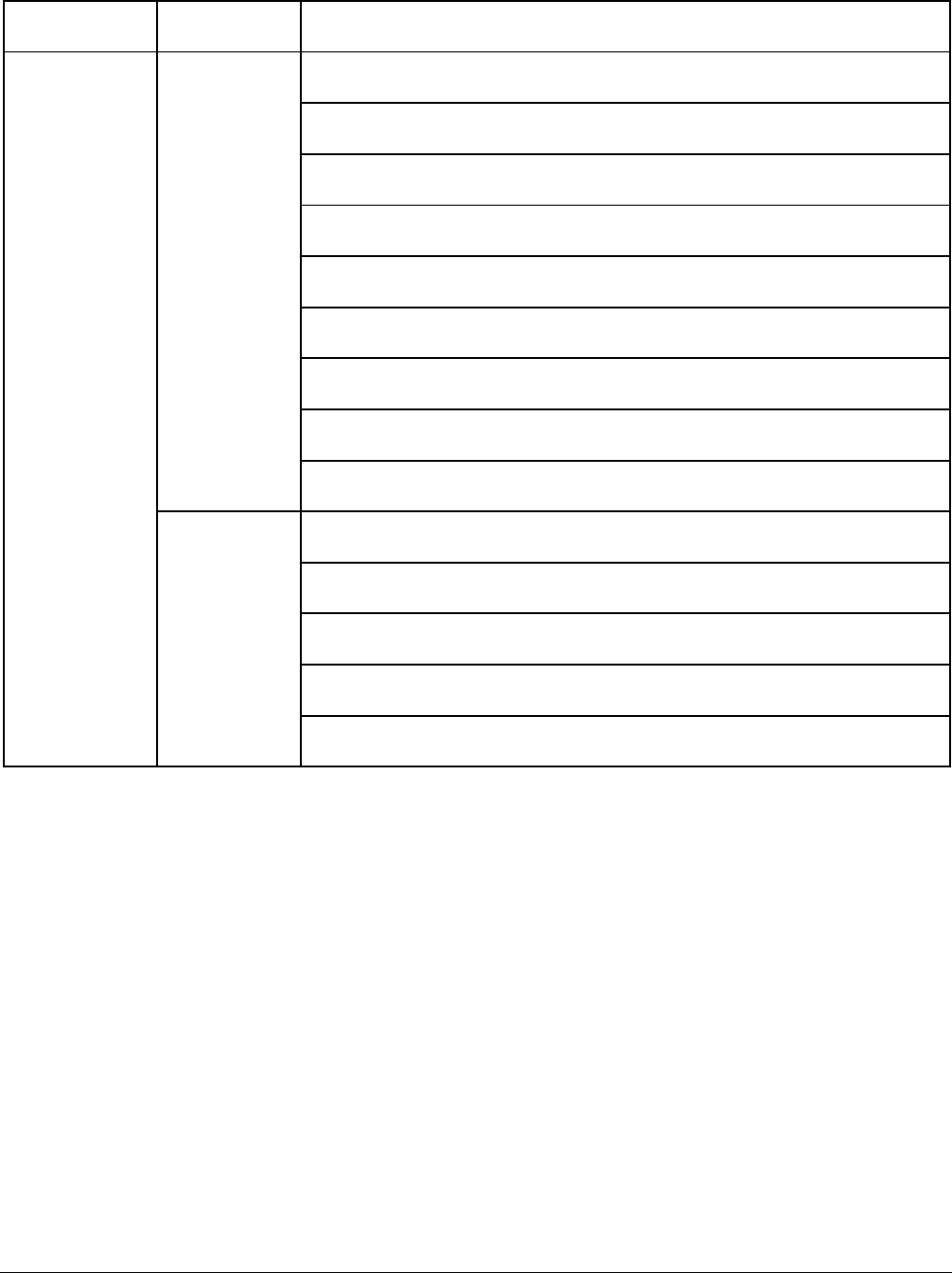

Table 4. Sample Responses on Most Memorable and Inappropriate Messages

Top

response

Among all the messages you saw

today, which one(s) were the most

memorable and why?

Do you think that any of the messages

today were inappropriate? If yes, which

ones?

1

“Buckle up and smell the rose”

“We pity the fool who texts & drives”

2

“72 were unbuckled”

“Luck of the Irish won’t help if you drive

drunk”

3

“It’s the temperature not the speed

limit”

“I think those messages contain too many

words”

4

“It’s ok to be a slow poke”

“I think they were ok. I think any jokes or

puns that make it take longer to read or

longer messages are distracting. short

jokes/puns ok.”

30

CHAPTER 5: PRELIMINARY DATA ANALYSIS

As mentioned in Chapter 4, each participant’s simulation game experience generates a series of data

trajectories that record their real-time actions to dynamic message signs seen along the drive. In this

preliminary data analysis, we are interested in analyzing if, and how, different types of nontraditional

messages can help improve safety with regard to five types of safety practice: (i) reducing average

driving speed, (ii) discouraging speeding, (iii) reducing phone use while driving, (iv) reducing honking

actions, and (v) encouraging seat belt usage.

We assume for simplicity that all participants’ reactions to various messages are independent of each

other, and the participants are memoryless of past messages. Since an average participant sees a new

message sign almost every 20–40 seconds (every 0.5 mile, based on the driving speed), we choose to

capture the effects of a nontraditional message simply by the difference between the participants’

observed safety practices 10 seconds before and 10 seconds after passing that message sign. These

periods will be referred to as “before” and “after” respectively.

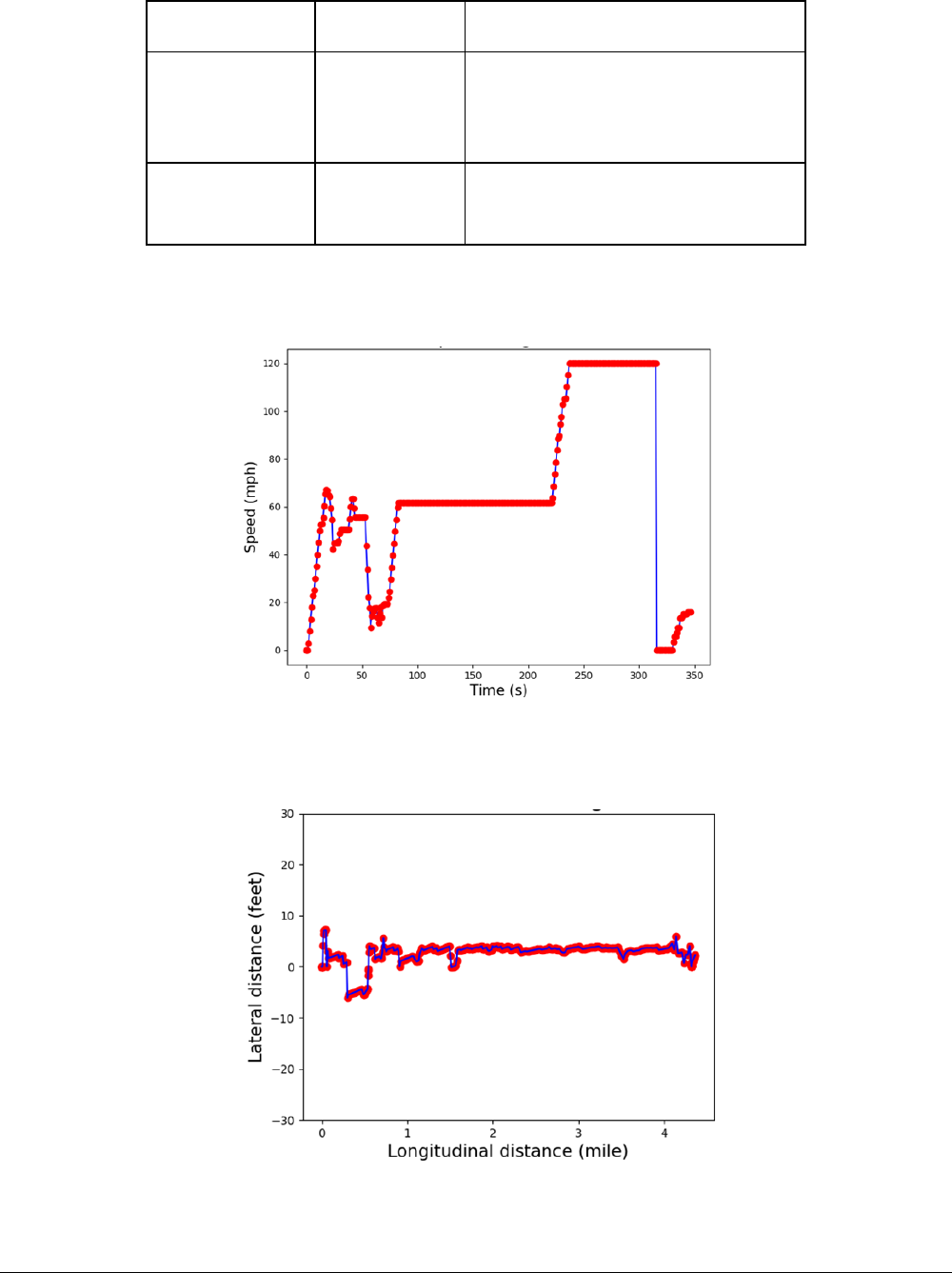

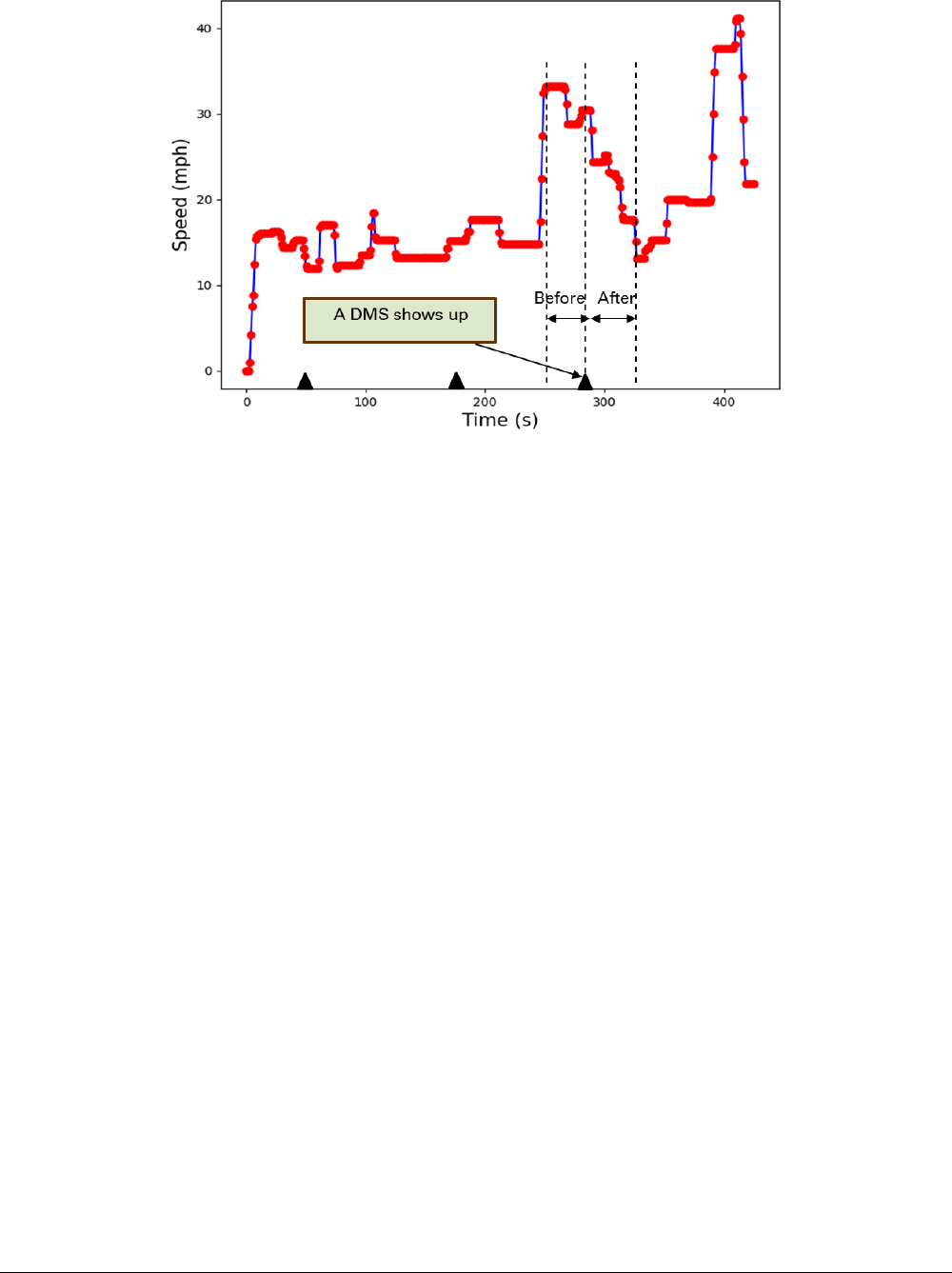

Figure 13 shows an example on how the effects of a message on reducing speed are measured

quantitatively. At the 277th second, a participant passed a sample message saying: “LIFE IS A

HIGHWAY DRIVE SAFELY ALL DAY LONG,” which belongs to category tag #1 in Table 1: “general safe

driving” and “emotionless.” The average speed in the before period of 267–277 seconds is 32 mph,

and that in the after period of 277–287 seconds is 22 mph. The difference of average speeds,

measured as the speed after passing the message minus the one before passing the message, is −10

mph. That particular message has a positive impact on reducing the average driving speed for this

particular observation. However, we must use statistics to draw more confident conclusions. To do

so, we make such measurements for each used dynamic message for each participant (grouped by

the category of the dynamic message target behavior and emotion) and conduct similar

measurements for each type of observed safety practice change. Then, we have 15 groups of

messages as well as five types of safety practice observations, and apply statistical analysis. All

participants’ reactions to three types of emotion messages in the target behavior category “general

safe driving” can be compared. For each of the five safety practice types, a two-sample t-test can be

applied between any two message groups to generate the -value and the -statistic. If the -value is

smaller than 0.05, then we are 95% confident that the two groups do not statistically have the

identical mean (or expected effect).

31

Figure 13. Graph. Quantitative analysis of speed reduction by message signs.

The remainder of this chapter will present preliminary analysis results on each of the five safety

practice types.

AVERAGE SPEED REDUCTION

Before-and-after data related to messages from categories 14–16 in Table 1 (“general aggressive

driving” + three types of emotions) are selected to analyze their impacts on average speed change.

For each observation, the average speed difference is computed as Equation 1:

=

−

(1)

where

and

represent the average speed in the after and before period, respectively. A

negative value of indicates a decrease in the average speed after seeing the sign.

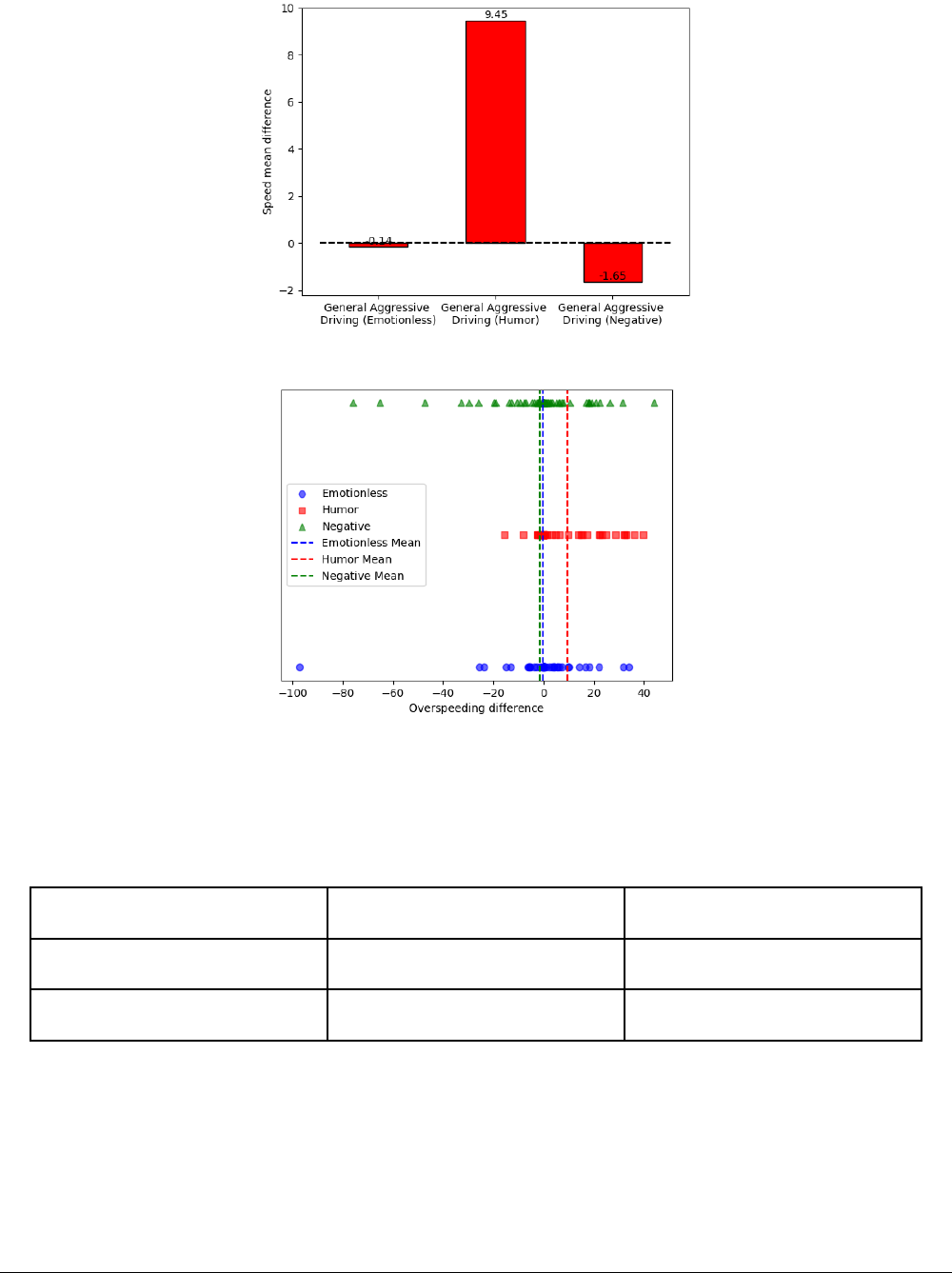

Figure 14-a and Figure 14-b show the means and distributions of , respectively, for the three types

of emotion messages. Negative emotion messages decrease the average speed by 1.65 mph, whereas

emotionless messages decrease speed only marginally by 0.14 mph, and humorous messages have a

strong “negative” effect of increasing speed by 9.45 mph.

Two-sample t-tests are conducted to see if there are statistically significant differences among these

types of emotions. Table 5 reports the results. We find with 99% confidence that messages with a

negative emotion are significantly more effective than emotionless or humorous ones. This also

indicates strongly that humorous messages should probably be avoided if we would like to remind

drivers to reduce speed.

32

(a) Mean of

(b) Distribution of

Figure 14. Graph. Effectiveness of three emotions in general safe driving to reduce speed.

Table 5. Two-Sample t-test between Three Emotions in Reducing Speed

t-statistic

p-value

Humor vs Negative

−3.05

0.00

Humor vs Emotionless

−2.59

0.01

SPEEDING

Before-and-after data related to messages from categories 14–16 in Table 1 (“general aggressive

driving” + three types of emotions) are selected to analyze their influences on speeding. For each

observation, the speeding difference is computed as Equation 2:

33

= 1(

≥ 60) − 1(

≥ 60) (2)

where 1(⋅) is a logical indicator function that equals 1 if the condition in the parentheses is true, or 0

otherwise;

and

represent the average speeds in the after and before period,

respectively. A negative value of indicates the participant stops speeding after passing the

message sign.

Figure 15 shows the mean of for three types of emotion messages. Emotionless messages can

reduce speeding by 4%, while negative messages reduce speeding by 2%, and humorous messages

have a counterproductive effect of increasing the chance of speeding by 11%.

Two-sample t-tests are conducted to measure the statistical difference among the three types of

emotions. Table 6 presents the results. We find with 97% confidence that emotionless messages are

more effective than humorous ones. Messages with a negative emotion also reduce speeding

compared with humorous ones, implying that humorous messages should be avoided in reminding

drivers about speeding. In general, this is consistent with findings on speed reduction—possibly

because humorous messages make drivers feel less serious about speed limits.

Figure 15. Graph. Effectiveness of three emotions to avoid speeding.

Table 6. Two-Sample t-test between Three Emotions to Avoid Speeding

t-statistic

p-value

Humor vs Negative

−1.81

0.07

Humor vs Emotionless

−2.25

0.03

34

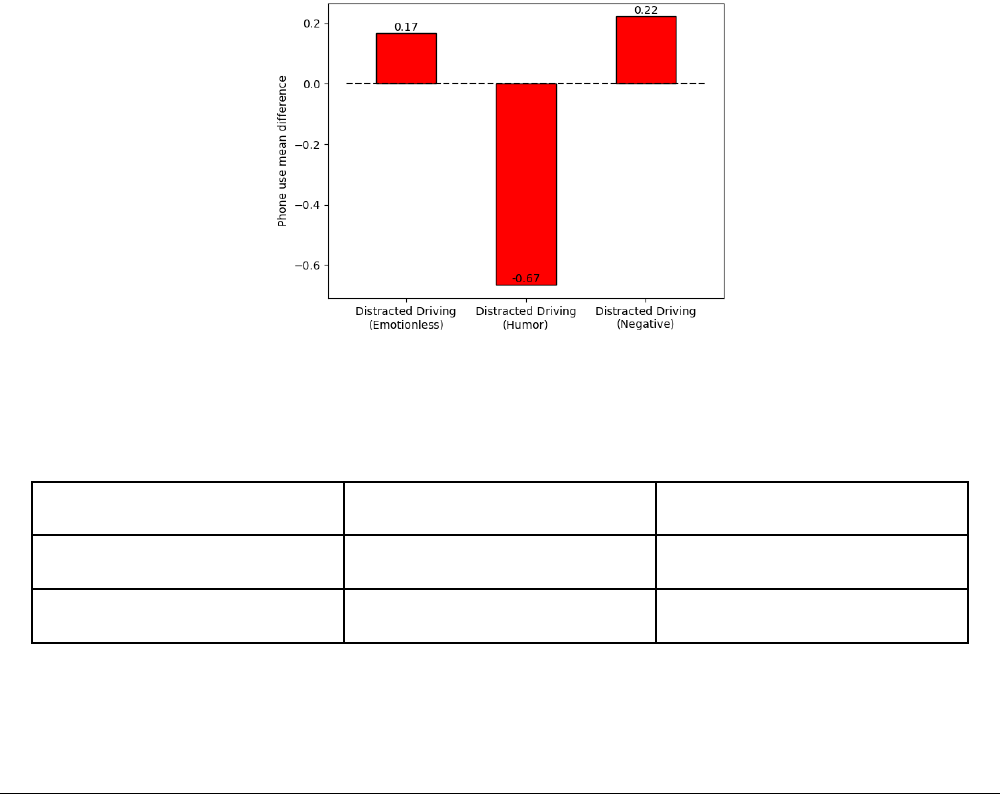

PHONE INTERACTIONS

Before-and-after data related to messages from categories 7–9 in Table 1 (distracted driving + three

emotions) under a high speed around 60–90 mph are selected to analyze their impacts on reducing

phone interactions. For each observation, the change in phone interaction number is computed as in

Equation 3:

=

−

(3)

where

and

represent the phone use number in the after and before period,

respectively. A negative represents the reduction of phone use after seeing a message sign. Figure

16 shows the mean of for three types of emotion messages. Humorous messages on distracted

driving can best reduce phone interactions by 0.67 times, while emotionless and negative messages

increase phone interactions by 0.17 and 0.22 times, respectively.

Two-sample t-tests are conducted to measure the statistical difference among the three emotions.

Table 7 presents the results. In particular, we find with 95% confidence that humorous messages are

more effective than emotionless ones. This implies that humorous messages could be effective in

reminding drivers to avoid phone use when they are driving at speeds between 60–90 mph.

Figure 16. Graph. Effectiveness of three emotions in distracted driving messages to reduce phone use.

Table 7. Two-Sample t-test between Three Emotions in Distracted Driving Messages to Reduce

Phone Use

t-statistic

p-value

Humor vs Negative

1.65

0.11

Humor vs Emotionless

2.16

0.05

35

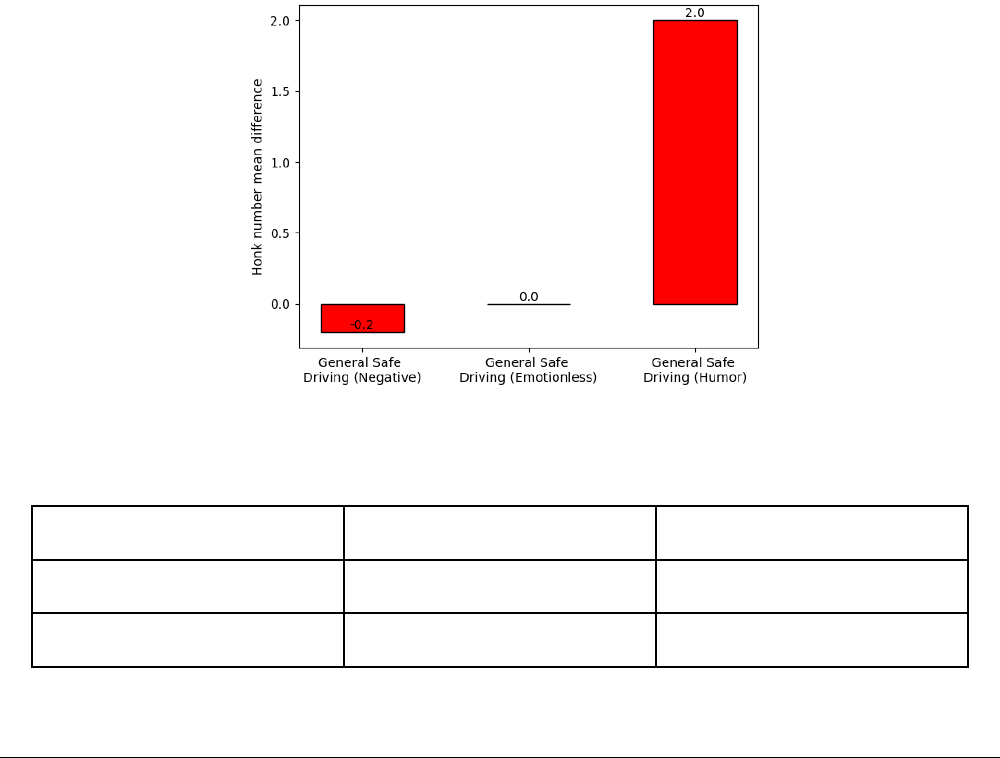

HONKING

Before-and-after data related to messages from categories 1–3 in Table 1 (general safe driving +

three types of emotions) when driving at speeds between 60–90 mph are selected to analyze their

effects on reducing honking. For each observation, the difference in honking number is computed as

Equation 4:

=

−

(4)

where

and

represent the number of honking actions in the after and before period,

respectively. A negative represents a reduction of honking after seeing a message sign.

Figure 17 shows the mean of for three types of emotion messages. Negative messages can reduce

honking by 0.2 times, and emotionless messages do not have notable impacts on the honking

number, while humorous messages have a counterproductive effect by increasing honking.

Two-sample t-tests are conducted to measure the statistical difference among three types of

message emotions. Results are shown in Table 8. We find that, with 98% confidence, negative

messages are more effective than humorous ones in reducing the frequency of honking. Humorous

messages probably should be avoided when the driving speed is around 60–90 mph.

Figure 17. Graph. Effectiveness of three emotions in general safe driving to reduce honking.

Table 8. Two-Sample t-test between Three Emotions in General Safe Driving to Reduce Honking

t-statistic

p-value

Humor vs Negative

−2.90

0.02

Humor vs Emotionless

−1.34

0.27

36

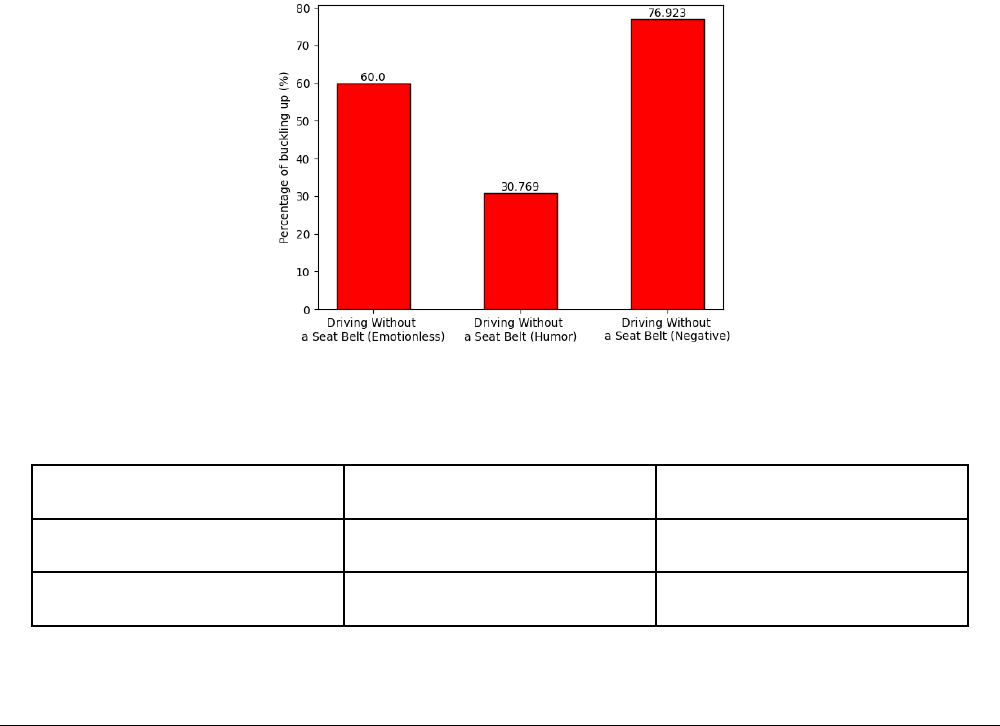

SEAT BELT USE

Before-and-after data related to messages from categories 4–6 in Table 1 (driving without seat belt +

three types of emotions) and having a speed lower than 60 mph are selected to measure the impacts

on seat belts. Note that only those not buckled in the before period are involved in this analysis. For

each observation, the change in seat belt status is computed as the effect of message signs in

Equation 5:

= 1(buckled after | unbuckled before) (5)

where 1(⋅) is the logical indicator function that equals 1 if the condition in the parentheses is true, or

0 otherwise. equals 1 if an unbuckled participant chooses to buckle up his or her seat belt after

seeing a message sign, or equals 0 otherwise. It can be interpreted as the conditional probability of

changing the buckling status. Figure 18 shows the mean of for three types of emotion messages.

For drivers previously not using a seat belt, negative messages can be most effective in reminding

about 77% to buckle up, emotionless messages can remind about 60%, and humorous messages are

least effective, only reminding 31% of participants to buckle up.

Table 9 shows the two-sample t-tests results. With 98% confidence, we conclude that negative

messages are more effective than humorous ones. This implies that negative messages could be most

effective in encouraging drivers to buckle up.

Figure 18. Graph. Effectiveness of three emotions in encouraging seat belt use.

Table 9. Two-Sample t-test among Three Emotions in Encouraging Seat Belt Use

t-statistic

p-value

Humor vs Negative

2.56

0.02

Humor vs Emotionless

0.85

0.41

37

ALTERNATIVE MESSAGE CATEGORIES

Please note that the categories of dynamic messages used in the previous sections are based on

those from the literature (i.e., Shealy et al., 2020). For some messages, especially for those under the

category of “emotionless,” their differences to “humorous” or “negative” can be subtle and highly

reliant on drivers’ interpretation and cultural background. For example, the message “DRIVING

SAFELY? I LIKE IT I LOVE IT” is classified as “emotionless” in Shealy et al. (2020); however, it also may

be considered “humorous” if one knows this is referring to the title of a song. Similarly, some of the

“emotionless” messages may be treated as “negative” due to individual drivers’ emotional mood or

perceptions. To test the robustness and accuracy of our statistical results, we conducted another

before-and-after analysis, using the same sample data and target driving behaviors, but with only two

message categories: humorous and negative. All messages in the emotionless category are

partitioned and re-grouped into the humorous and negative categories. Appendix C presents the new

list of messages by these two groups. Table 10 summarizes their relative frequency of use in the

simulation games, under the new categories.

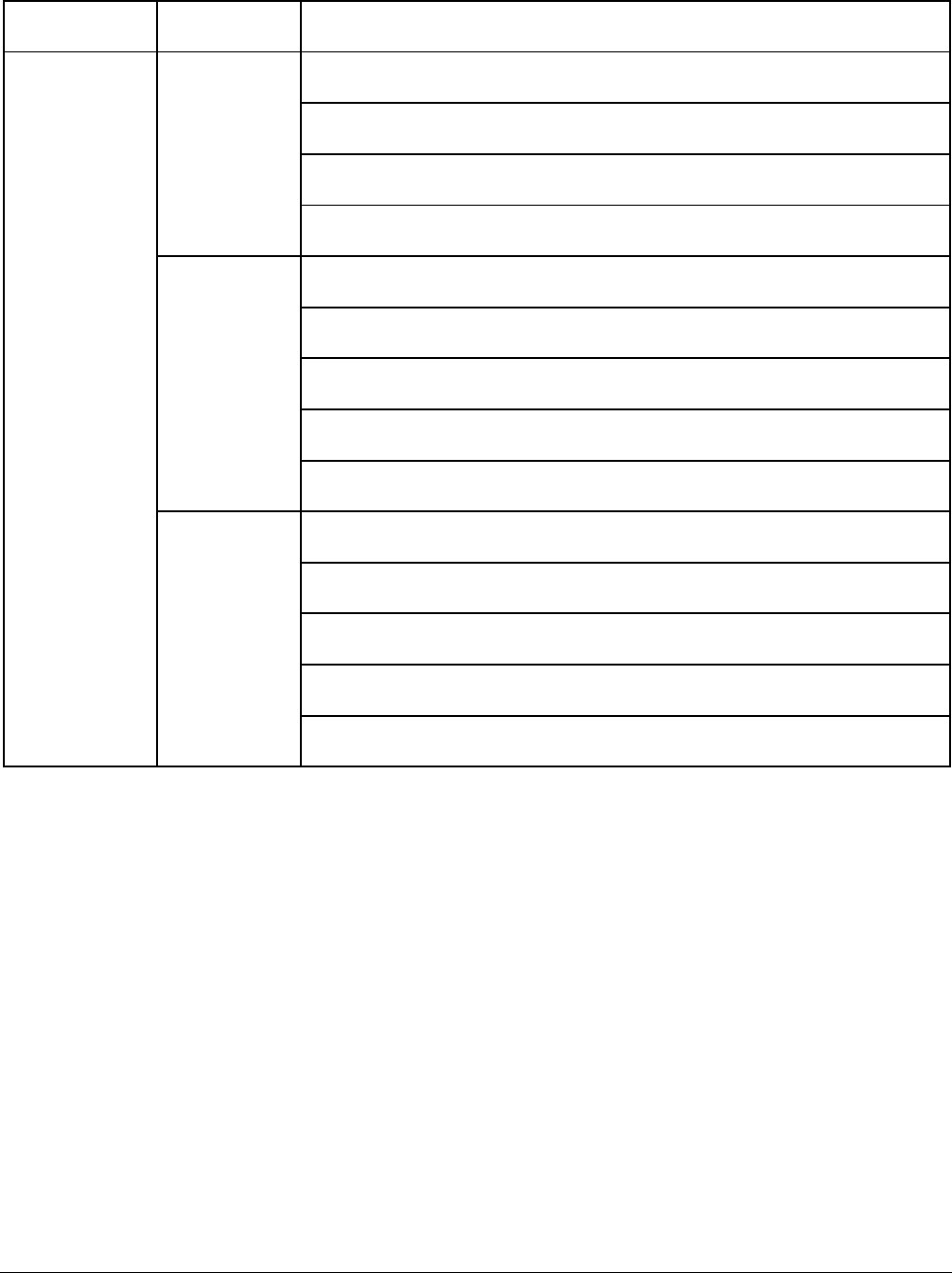

Table 10. Nontraditional Messages Grouped by Target Behavior and Adjusted Emotion

Index

Behavior

Emotion

Frequency of use (%)

1

General safe driving

Humorous

13.70

2

General safe driving

Negative

3.80

3

Driving without a seat belt

Humorous

13.57

4

Driving without a seat belt

Negative

5.97

5

Distracted driving

Humorous

17.23

6

Distracted driving

Negative

7.19

7

Impaired and drowsy driving

Humorous

11.80

8

Impaired and drowsy driving

Negative

7.19

9

General aggressive driving

Humorous

11.13

10

General aggressive driving

Negative

8.42

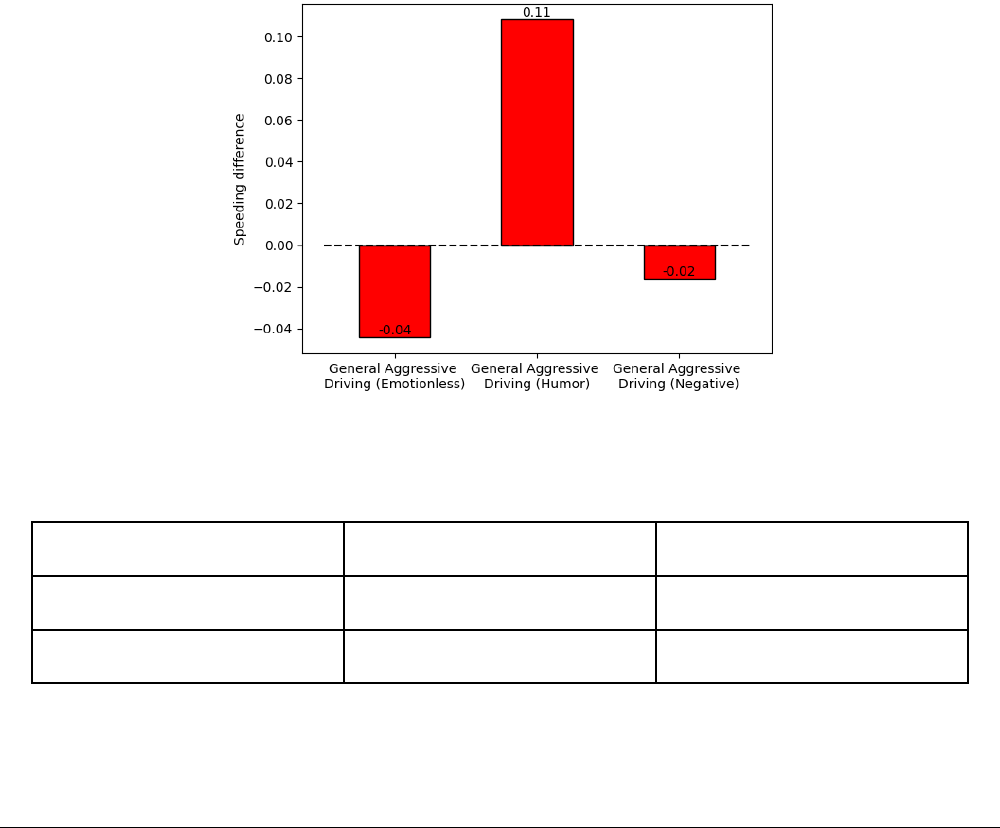

Table 11 summarizes the two-sample t-tests results for five target safe driving behaviors with the

new message categories in specific driving speed ranges. With 96.6% confidence, we conclude that

the negative messages are more effective than humorous ones in encouraging speed reduction for

those driving slower than 60 mph. With 98% confidence, we conclude that negative messages are

more effective than humorous ones in avoiding speeding. With 96.5% confidence, we conclude that

38

humorous messages are more effective than negative ones in avoiding phone use when drivers are

driving at 60–120 mph. With 96.8% confidence, we conclude that negative messages are more

effective than humorous ones in encouraging seatbelt use when drivers are driving at 40–120 mph.

These results are generally consistent with those found in the previous subsections. The only

exception is about reducing honking, where no statistically significant difference is found.

Table 11. Two-Sample t-test among Emotions with New Categorization

Safety Behavior

/ Practice

Message

Category

Speed Range

(mph)

Mean

(Humorous)

Mean

(Negative)

t-statistic p-value

Average speed

reduction

(9) (10) 0–60 4.26 −2.17 2.18 0.034

Speeding (9) (10) 0–120 0.11 −0.03 2.37 0.019

Phone

interaction

(5) (6) 60–120 −0.46 0.2 −2.16 0.035

Honking – – – – – –

Seatbelt use (1) (2) 40–120 0.37 0.0 2.24 0.032

39

CHAPTER 6: CONCLUSION

This project completed three main tasks. First, a literature review was conducted to investigate past

studies researching driver behaviors and different types of dynamic message signs as well as to

explore similar projects experimenting on the effect of drivers’ behavior change caused by dynamic

message signs. Second, a web-based questionnaire and simulation were developed to capture

drivers’ opinions and behaviors toward dynamic message signs in a semi-realistic environment. Third,

a preliminary data analysis was conducted to develop a better understanding of how dynamic

message signs influence driver behaviors and to provide suggestions how IDOT may systematically

present information on dynamic message signs in practice. Some of the key findings are listed below:

• Avoid humorous messages when encouraging drivers to decrease speed.

• Use emotionless messages to discourage drivers from speeding.

• Use humorous messages when encouraging drivers to reduce frequency of texting and calling

when driving speed is 60–90 mph.

• Avoid humorous messages when discouraging drivers from honking at another driver when

driving speed is 60–90 mph.

• Negative messages are recommended in encouraging drivers to buckle up when driving speed

is lower than 60 mph.

The proposed online driving game and survey are able to protect the privacy of respondents and are

sufficiently robust for future extensions and adaptations to a more complex environment, such as

lighting conditions, weather conditions, road geometry, or traffic congestion. Additionally, any type of

nontraditional messages can be easily loaded and tested in the driving game. It is also possible to

investigate nontraditional messages’ effectiveness using a more sophisticated model, such as

trajectory data mining and deep learning, rather than making simplified assumptions and using

traditional statistical tests. The online driving game is expected to handle larger-scale experiments

and provide more comprehensive and valuable information in the future.

This study produces a synthesis of the available literature and preliminary data analysis of the driver

survey/experiment, and the findings provide recommendations for IDOT on the most effective

messages for Illinois. The result illustrates what type of message (emotionless, negative, humorous)

changes driver behavior for increased compliance and decreased crash activity. This project also

generates findings that will serve as guidance on when and where different kinds of messages may be

most effective, providing a long-term benefit to IDOT and partner agencies.

40

REFERENCES

Boyle, L., Cordahi, G., Grabenstein, K., Madi, M., Miller, E., & Silberman, P. (2014). Effectiveness of

safety and public service announcement (PSA) messages on dynamic message signs (DMS) (Report

No FHWA-HOP-14-015). Federal Highway Administration.

Francis, J. (2018). Unusual highway signs grab drivers’ attention. News Channel 20, November 29.

https://newschannel20.com/news/local/unusual-highway-signs-grab-drivers-attention.

Haghani, A., Hamedi, M., Fish, R., & Norouzi, A. (2013). Evaluation of dynamic message signs and their

potential impact on traffic flow (Report No. MD-13-SP109B4C). Maryland State Highway

Administration.

Harder, K. A., & Bloomfield, J. R. (2008). The effectiveness and safety of traffic and non-traffic related

messages presented on changeable message signs—Phase II (Report No. Mn/DOT 2008-27).

Minnesota Department of Transportation.

Huang, Y., Strawderman, L., & Garrison, T. (2013). Dynamic Message Signs, Driver Characteristics, and

Speed Reduction. IIE Annual Conference. Proceedings

Rodier, C. J., Lidicker, J. R., Finson, R. S., & Shaheen, S. A. (2010). An evaluation of the consequences

and effectiveness of using highway changeable message signs for safety campaigns (Report No.

CA10-1124). University of California PATH. https://trid.trb.org/view/919831

Schroeder, J., Plapper, E., Zeng, H., & Krile, B. (2016). Public perception of safety messages and public

service announcements on dynamic message signs in rural areas (Report No. FHWA-HOP-16-048).

U.S. Department of Transportation. Federal Highway Administration.

Shealy, T., Kryschtal, P., Franczek, K., & Katz, B. J. (2020). Driver response to dynamic message sign

safety campaign messages (Report No. FHWA/VTRC 20-R16). Virginia Transportation Research

Council. http://www.virginiadot.org/vtrc/main/online_reports/pdf/20-r16.pdf

Shroeder, J., & Demetsky, M. (2010). Evaluation of driver reactions for effective use of dynamic

message signs in Richmond, Virginia (Report No. FHWA/VTRC 10-R16). Virginia Transportation

Research Council.

Song, M., Wang, J., Cheung, Sam., & Keceli, M. (2016). Assessing and mitigating the impacts of

dynamic message signs on highway traffic. International Journal for Traffic and Transportation

Engineering, 6(1), 1–12.

Strawderman, L., Huang, Y., & Garrison, T. (2013) The effect of design and placement of work-zone

warning signs on driver speed compliance: A simulator-based study. IIE Transactions on

Occupational Ergonomics and Human Factors, 1(1), 66–75.

https://doi.org/10.1080/21577323.2012.714839

41

APPENDIX A: NONTRADITIONAL MESSAGES

Table 12. List of Nontraditional Messages Used in the Simulation Game

Behavior

Emotion

Messages

General safe

driving

Emotionless

NOBODY PUTS BABY IN A HOT CAR

DON’T YOU FORGET ABOUT ME AS YOU DRIVE ON BY

LIFE IS A HIGHWAY DRIVE SAFELY ALL DAY LONG

BE OUR GUEST DRIVE POLITELY

DRIVING SAFELY? I LIKE IT I LOVE IT

Humor

BE ON SANTA'S NICE LIST DRIVE POLITELY

WHAT'S SCARIER YOUR COSTUME OR YOUR DRIVING?

BE A FIREWORK SPARK RESPONSIBLE DRIVING

ZERO FATALITIES A GHOUL WE CAN ALL LIVE WITH

SANTA'S COMING HAVE YOU BEEN A GOOD DRIVER?

Negative

843 VA FATALITIES THIS YEAR DRIVE SAFELY

375 MILLION US VEHICLE INJURIES IN 2017

843 TRAFFIC DEATHS IN VIRGINIA THIS YEAR DRIVE ALERT

757 FATALITIES SONS, DAUGHTERS. STOP THE HEARTACHE

843 FATALITIES ON VIRGINIA ROADS IN 2018

Driving

without a

seatbelt

Emotionless

PROTECT YOURSELF BUCKLE UP

SECURE THE FUTURE BUCKLE YOUR CHILD

DON’T LEAP FROM YOUR SEAT BUCKLE UP

SEE YOUR BFF TONIGHT BUCKLE UP

BUCKLE UP SAVE $25 AND YOUR LIFE

Humor

DON’T MAKE ME STOP THIS CAR! BUCKLE UP

42

Behavior

Emotion

Messages

DUCK, DUCK, BUCKLE UP

AWWWWW SNAP! YOUR SEAT BELT!

BUCKLE UP AND SMELL THE ROSES

PEACE LOVE SEATBELTS BUCKLE UP!

Negative

72 WERE UNBUCKLED

9 OF 17 FATALITIES UNBUCKLED THIS YEAR

153 ROAD DEATHS IN VA THIS YEAR 66% UNBUCKLED

37% FATALITIES WERE NOT WEARING SEATBELTS

60% OF TEEN ROAD DEATHS IN VIRGINIA ARE UNBUCKLED

Distracted

driving

Emotionless

GOLD MEDAL DRIVERS DON’T TEXT AND DRIVE

MAKE IT TO THE END ZONE DRIVE ALERT

DON’T LET SAFETY BE A HAIL MARY DRIVE ALERT

PLAY BALL! STRIKE THE DISTRACTIONS

BLOW THE WHISTLE ON DISTRACTED DRIVING

Humor

GET YOUR HEAD OUT OF YOUR APPS

TEXTING WHILE DRIVING? OH CELL NO.

DON’T DRIVE IN-TEXT-ICATED

AVOID AN APPSIDENT PHONES DOWN