A Computational Approach to Automatic Prediction of Drunk-Texting

Aditya Joshi

1,2,3

Abhijit Mishra

1

Balamurali AR

4

Pushpak Bhattacharyya

1

Mark James Carman

2

1

IIT Bombay, India,

2

Monash University, Australia

3

IITB-Monash Research Academy, India

4

Aix-Marseille University, France

{adityaj, abhijitmishra, pb}@cse.iitb.ac.in

Abstract

Alcohol abuse may lead to unsociable

behavior such as crime, drunk driving,

or privacy leaks. We introduce auto-

matic drunk-texting prediction as the task

of identifying whether a text was writ-

ten when under the influence of alcohol.

We experiment with tweets labeled using

hashtags as distant supervision. Our clas-

sifiers use a set of N-gram and stylistic fea-

tures to detect drunk tweets. Our observa-

tions present the first quantitative evidence

that text contains signals that can be ex-

ploited to detect drunk-texting.

1 Introduction

The ubiquity of communication devices has made

social media highly accessible. The content on

these media reflects a user’s day-to-day activities.

This includes content created under the influence

of alcohol. In popular culture, this has been re-

ferred to as ‘drunk-texting’

1

. In this paper, we in-

troduce automatic ‘drunk-texting prediction’ as a

computational task. Given a tweet, the goal is to

automatically identify if it was written by a drunk

user. We refer to tweets written under the influ-

ence of alcohol as ‘drunk tweets’, and the opposite

as ‘sober tweets’.

A key challenge is to obtain an annotated

dataset. We use hashtag-based supervision so that

the authors of the tweets mention if they were

drunk at the time of posting a tweet. We create

three datasets by using different strategies that are

related to the use of hashtags. We then present

SVM-based classifiers that use N-gram and stylis-

tic features such as capitalisation, spelling errors,

etc. Through our experiments, we make subtle

points related to: (a) the performance of our fea-

tures, (b) how our approach compares against

1

Source: http://www.urbandictionary.com

human ability to detect drunk-texting, (c) most

discriminative stylistic features, and (d) an error

analysis that points to future work. To the best of

our knowledge, this is a first study that shows the

feasibility of text-based analysis for drunk-texting

prediction.

2 Motivation

Past studies show the relation between alcohol

abuse and unsociable behaviour such as aggres-

sion (Bushman and Cooper, 1990), crime (Carpen-

ter, 2007), suicide attempts (Merrill et al., 1992),

drunk driving (Loomis and West, 1958), and risky

sexual behaviour (Bryan et al., 2005). Merrill et

al. (1992) state that “those responsible for assess-

ing cases of attempted suicide should be adept at

detecting alcohol misuse”. Thus, a drunk-texting

prediction system can be used to identify individ-

uals susceptible to these behaviours, or for inves-

tigative purposes after an incident.

Drunk-texting may also cause regret. Mail

Goggles

2

prompts a user to solve math questions

before sending an email on weekend evenings.

Some Android applications

3

avoid drunk-texting

by blocking outgoing texts at the click of a button.

However, to the best of our knowledge, these tools

require a user command to begin blocking. An on-

going text-based analysis will be more helpful, es-

pecially since it offers a more natural setting by

monitoring stream of social media text and not ex-

plicitly seeking user input. Thus, automatic drunk-

texting prediction will improve systems aimed to

avoid regrettable drunk-texting. To the best of

our knowledge, ours is the first study that does a

quantitative analysis, in terms of prediction of the

drunk state by using textual clues.

Several studies have studied linguistic traits

associated with emotion expression and mental

2

http://gmailblog.blogspot.in/2008/10/new-in-labs-stop-

sending-mail-you-later.html

3

https://play.google.com/store/apps/details?id=com.oopsapp

health issues, suicidal nature, criminal status, etc.

(Pennebaker, 1993; Pennebaker, 1997). NLP tech-

niques have been used in the past to address so-

cial safety and mental health issues (Resnik et al.,

2013).

3 Definition and Challenges

Drunk-texting prediction is the task of classifying

a text as drunk or sober. For example, a tweet

‘Feeling buzzed. Can’t remember how the evening

went’ must be predicted as ‘drunk’, whereas, ‘Re-

turned from work late today, the traffic was bad’

must be predicted as ‘sober’. The challenges are:

1. More than topic categorisation: Drunk-

texting prediction is similar to topic cate-

gorisation (that is, classification of docu-

ments into a set of categories such as ‘news’,

‘sports’, etc.). However, Borrill et al. (1987)

show that alcohol abusers have more pro-

nounced emotions, specifically, anger. In this

respect, drunk-texting prediction lies at the

confluence of topic categorisation and emo-

tion classification.

2. Identification of labeled examples: It is dif-

ficult to obtain a set of sober tweets. The

ideal label can be possibly given only by the

author. For example, whether a tweet such

as ‘I am feeling lonely tonight’ is a drunk

tweet is ambiguous. This is similar to sar-

casm expressed as an exaggeration (for ex-

ample, ‘This is the best film ever!), where the

context beyond the text needs to be consid-

ered.

3. Precision/Recall trade-off: The goal that a

drunk-texting prediction system must chase

depends on the application. An application

that identifies potential crimes must work

with high precision, since the target popula-

tion to be monitored will be large. On the

other hand, when being used to avoid regret-

table drunk-texting, a prediction system must

produce high recall in order to ensure that a

drunk message does not pass through.

4 Dataset Creation

We use hashtag-based supervision to create our

datasets, similar to tasks like emotion classifica-

tion (Purver and Battersby, 2012). The tweets are

downloaded using Twitter API (https://dev.

twitter.com/). We remove non-Unicode

characters, and eliminate tweets that contain hy-

perlinks

4

and also tweets that are shorter than 6

words in length. Finally, hashtags used to indi-

cate drunk or sober tweets are removed so that

they provide labels, but do not act as features. The

dataset is available on request. As a result, we cre-

ate three datasets, each using a different strategy

for sober tweets, as follows:

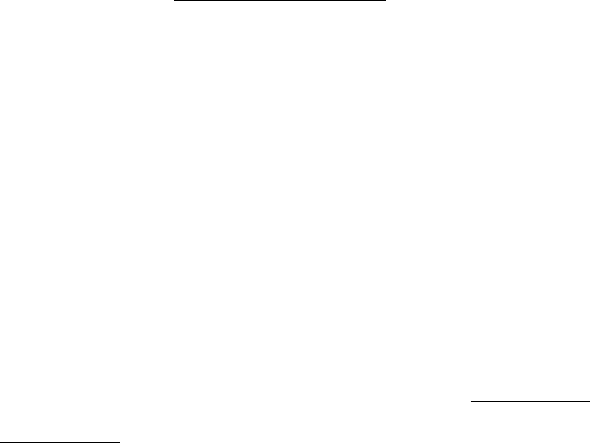

Figure 1: Word cloud for drunk tweets

1. Dataset 1 (2435 drunk, 762 sober): We col-

lect tweets that are marked as drunk and

sober, using hashtags. Tweets containing

hashtags #drunk, #drank and #imdrunk are

considered to be drunk tweets, while those

with #notdrunk, #imnotdrunk and #sober are

considered to be sober tweets.

2. Dataset 2 (2435 drunk, 5644 sober): The

drunk tweets are downloaded using drunk

hashtags, as above. The list of users who cre-

ated these tweets is extracted. For the nega-

tive class, we download tweets by these users,

which do not contain the hashtags that corre-

spond to drunk tweets.

3. Dataset H (193 drunk, 317 sober): A sepa-

rate dataset is created where drunk tweets are

downloaded using drunk hashtags, as above.

The set of sober tweets is collected using both

the approaches above. The resultant is the

held-out test set Dataset-H that contains no

tweets in common with Datasets 1 and 2.

The drunk tweets for Datasets 1 and 2 are

the same. Figure 1 shows a word-cloud for

these drunk tweets (with stop words and forms

of the word ‘drunk’ removed), created using

4

This is a rigid criterion, but we observe that tweets with

hyperlinks are likely to be promotional in nature.

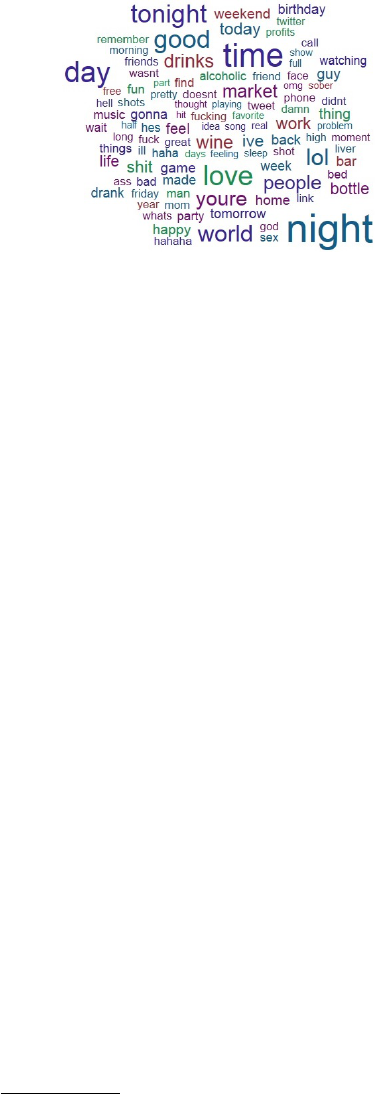

Feature Description

N-gram Features

Unigram & Bigram (Presence) Boolean features indicating unigrams and bigrams

Unigram & Bigram (Count) Real-valued features indicating unigrams and bigrams

Stylistic Features

LDA unigrams (Presence/Count) Boolean & real-valued features indicating unigrams from LDA

POS Ratio Ratios of nouns, adjectives, adverbs in the tweet

#Named Entity Mentions Number of named entity mentions

#Discourse Connectors Number of discourse connectors

Spelling errors Boolean feature indicating presence of spelling mistakes

Repeated characters Boolean feature indicating whether a character is repeated three

times consecutively

Capitalisation Number of capital letters in the tweet

Length Number of words

Emoticon (Presence/Count) Boolean & real-valued features indicating unigrams

Sentiment Ratio Positive and negative word ratios

Table 1: Our Feature Set for Drunk-texting Prediction

WordItOut

5

. The size of a word indicates its fre-

quency. In addition to topical words such as ‘bar’,

‘bottle’ and ‘wine’, the word-cloud shows senti-

ment words such as ‘love’ or ‘damn’, along with

profane words.

Heuristics other than these hashtags could have

been used for dataset creation. For example,

timestamps were a good option to account for time

at which a tweet was posted. However, this could

not be used because user’s local times was not

available, since very few users had geolocation en-

abled.

5 Feature Design

The complete set of features is shown in Table 1.

There are two sets of features: (a) N-gram fea-

tures, and (b) Stylistic features. We use unigrams

and bigrams as N-gram features- considering both

presence and count.

Table 1 shows the complete set of stylistic fea-

tures of our prediction system. POS ratios are a set

of features that record the proportion of each POS

tag in the dataset (for example, the proportion of

nouns/adjectives, etc.). The POS tags and named

entity mentions are obtained from NLTK (Bird,

2006). Discourse connectors are identified based

on a manually created list. Spelling errors are

identified using a spell checker by Aby (2014).

The repeated characters feature captures a situ-

ation in which a word contains a letter that is

repeated three or more times, as in the case of

5

www.worditout.com

happpy. Since drunk-texting is often associated

with emotional expression, we also incorporate a

set of sentiment-based features. These features in-

clude: count/presence of emoticons and sentiment

ratio. Sentiment ratio is the proportion of posi-

tive and negative words in the tweet. To deter-

mine positive and negative words, we use the sen-

timent lexicon in Wilson et al. (2005). To identify

a more refined set of words that correspond to the

two classes, we also estimated 20 topics for the

dataset by estimating an LDA model (Blei et al.,

2003). We then consider top 10 words per topic,

for both classes. This results in 400 LDA-specific

unigrams that are then used as features.

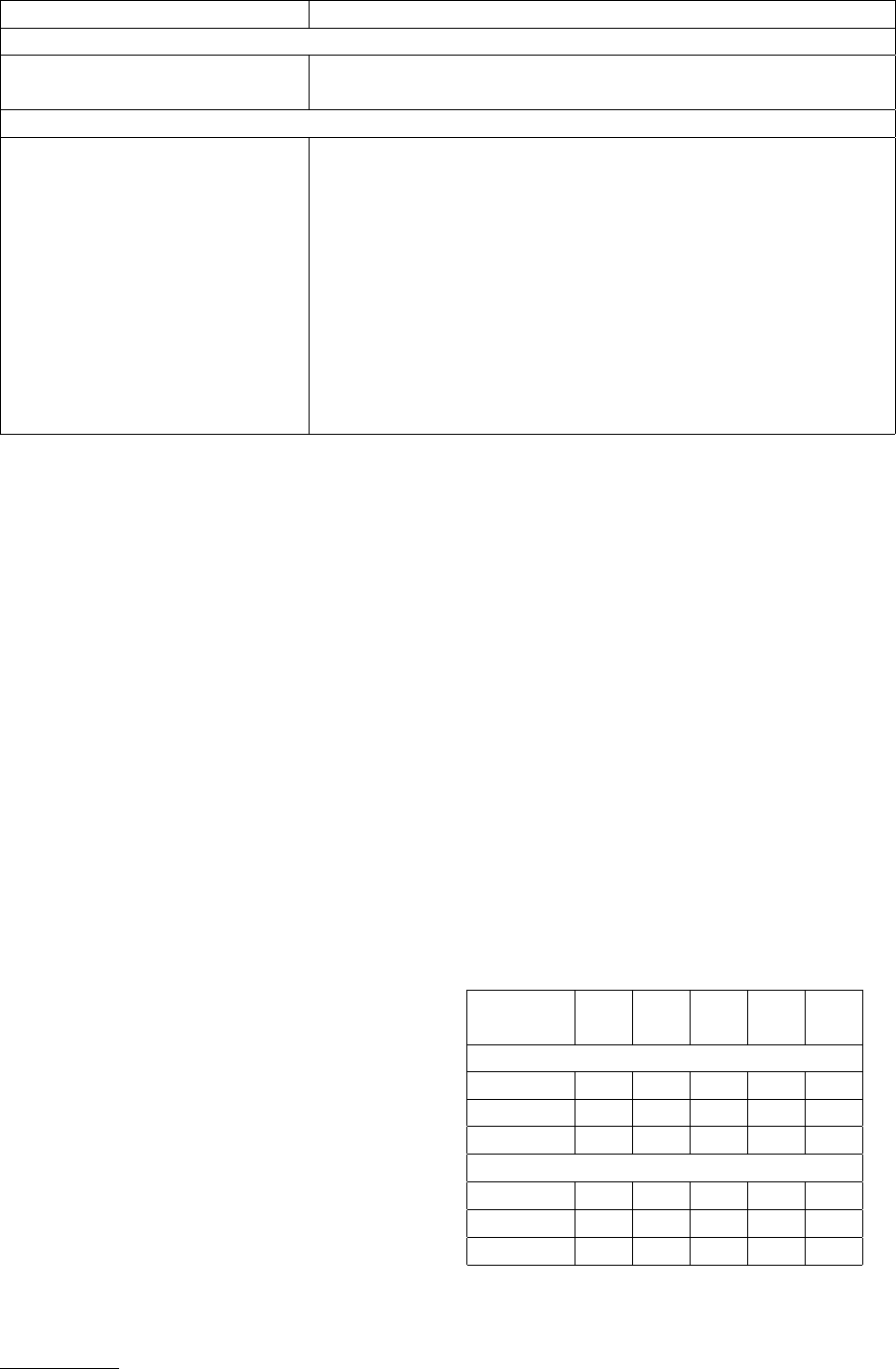

A

(%)

NP

(%)

PP

(%)

NR

(%)

PR

(%)

Dataset 1

N-gram 85.5 72.8 88.8 63.4 92.5

Stylistic 75.6 32.5 76.2 3.2 98.6

All 85.4 71.9 89.1 64.6 91.9

Dataset 2

N-gram 77.9 82.3 65.5 87.2 56.5

Stylistic 70.3 70.8 56.7 97.9 6.01

All 78.1 82.6 65.3 86.9 57.5

Table 2: Performance of our features on Datasets

1 and 2

6 Evaluation

Using the two sets of features, we train SVM clas-

sifiers (Chang and Lin, 2011)

6

. We show the

five-fold cross-validation performance of our fea-

tures on Datasets 1 and 2, in Section 6.1, and on

Dataset H in Section 6.2. Section 6.3 presents an

error analysis. Accuracy, positive/negative preci-

sion and positive/negative recall are shown as A,

PP/NP and PR/NR respectively. ‘Drunk’ forms

the positive class, while ‘Sober’ forms the nega-

tive class.

Top features

# Dataset 1 Dataset 2

1 POS NOUN Spelling error

2 Capitalization LDA drinking

3 Spelling error POS NOUN

4 POS PREPOSITION Length

5 Length LDA tonight

6 LDA Llife Sentiment Ratio

7 POS VERB Char repeat

8 LDA today LDA today

9 POS ADV LDA drunken

10 Sentiment Ratio LDA lmao

Table 3: Top stylistic features for Datasets 1 and 2

obtained using Chi-squared test-based ranking

6.1 Performance for Datasets 1 and 2

Table 2 shows the performance for five-fold cross-

validation for Datasets 1 and 2. In case of Dataset

1, we observe that N-gram features achieve an ac-

curacy of 85.5%. We see that our stylistic features

alone exhibit degraded performance, with an ac-

curacy of 75.6%, in the case of Dataset 1. Ta-

ble 3 shows top stylistic features, when trained

on the two datasets. Spelling errors, POS ratios

for nouns (POS NOUN)

7

, length and sentiment

ratios appear in both lists, in addition to LDA-

based unigrams. However, negative recall reduces

to a mere 3.2%. This degradation implies that

our features capture a subset of drunk tweets and

that there are properties of drunk tweets that may

be more subtle. When both N-gram and stylis-

tic features are used, there is negligible improve-

ment. The accuracy for Dataset 2 increases from

6

We also repeated all experiments for Na

¨

ıve Bayes. They

do not perform as well as SVM, and have poor recall.

7

POS ratios for nouns, adjectives and adverbs were nearly

similar in drunk and sober tweets - with the maximum differ-

ence being 0.03%

77.9% to 78.1%. Precision/Recall metrics do not

change significantly either. The best accuracy of

our classifier is 78.1% for all features, and 75.6%

for stylistic features. This shows that text-based

clues can indeed be used for drunk-texting predic-

tion.

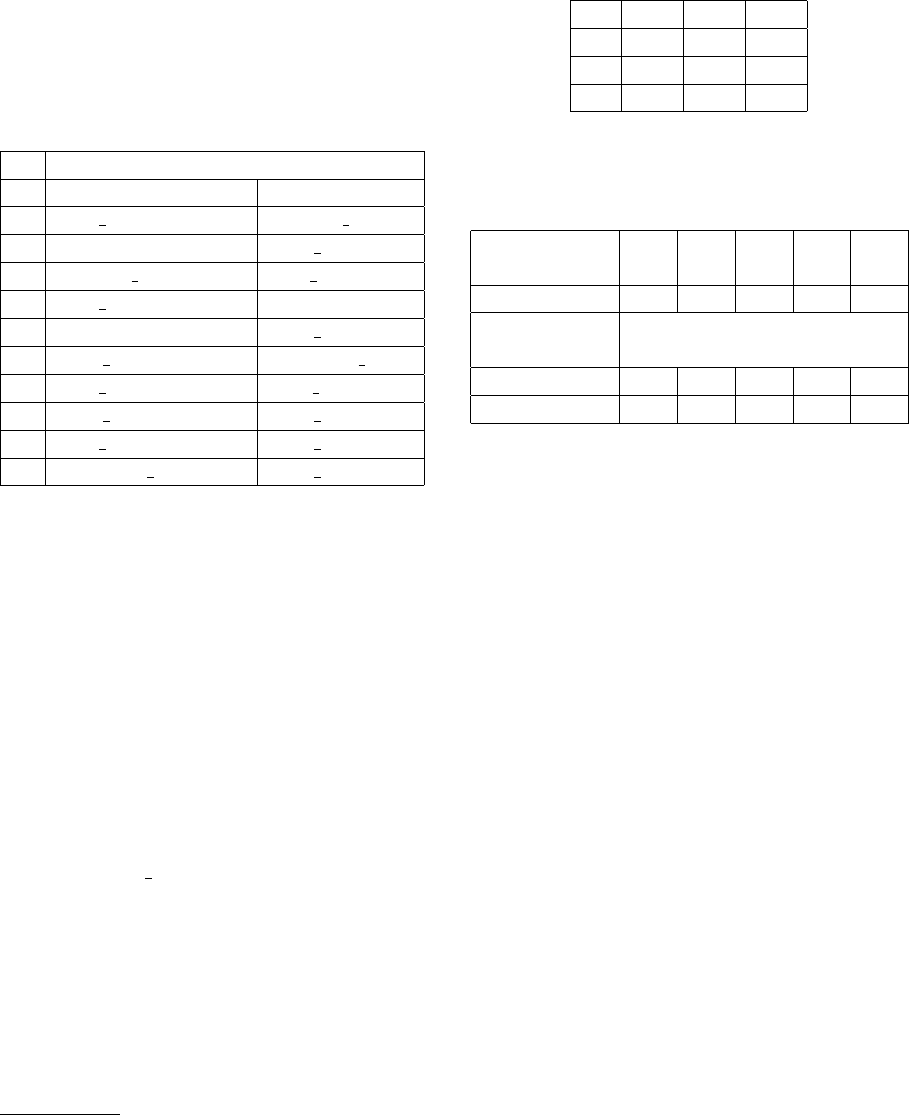

A1 A2 A3

A1 - 0.42 0.36

A2 0.42 - 0.30

A3 0.36 0.30 -

Table 4: Cohen’s Kappa for three annotators (A1-

A3)

A

(%)

NP

(%)

PP

(%)

NR

(%)

PR

(%)

Annotators 68.8 71.7 61.7 83.9 43.5

Training

Dataset

Our classifiers

Dataset 1 47.3 70 40 26 81

Dataset 2 64 70 53 72 50

Table 5: Performance of human evaluators and our

classifiers (trained on all features), for Dataset-H

as the test set

6.2 Performance for Held-out Dataset H

Using held-out dataset H, we evaluate how our

system performs in comparison to humans. Three

annotators, A1-A3, mark each tweet in the Dataset

H as drunk or sober. Table 4 shows a moderate

agreement between our annotators (for example,

it is 0.42 for A1 and A2). Table 5 compares our

classifier with humans. Our human annotators per-

form the task with an average accuracy of 68.8%,

while our classifier (with all features) trained on

Dataset 2 reaches 64%. The classifier trained on

Dataset 2 is better than which is trained on Dataset

1.

6.3 Error Analysis

Some categories of errors that occur are:

1. Incorrect hashtag supervision: The tweet

‘Can’t believe I lost my bag last night, lit-

erally had everything in! Thanks god the

bar man found it’ was marked with‘#Drunk’.

However, this tweet is not likely to be a drunk

tweet, but describes a drunk episode in retro-

spective. Our classifier predicts it as sober.

2. Seemingly sober tweets: Human annotators

as well as our classifier could not identify

whether ‘Will you take her on a date? But

really she does like you’ was drunk, although

the author of the tweet had marked it so.

This example also highlights the difficulty of

drunk-texting prediction.

3. Pragmatic difficulty: The tweet ‘National

dress of Ireland is one’s one vomit.. my fam-

ily is lovely’ was correctly identified by our

human annotators as a drunk tweet. This

tweet contains an element of humour and

topic change, but our classifier could not cap-

ture it.

7 Conclusion & Future Work

In this paper, we introduce automatic drunk-

texting prediction as the task of predicting a tweet

as drunk or sober. First, we justify the need for

drunk-texting prediction as means of identifying

risky social behavior arising out of alcohol abuse,

and the need to build tools that avoid privacy leaks

due to drunk-texting. We then highlight the chal-

lenges of drunk-texting prediction: one of the

challenges is selection of negative examples (sober

tweets). Using hashtag-based supervision, we cre-

ate three datasets annotated with drunk or sober

labels. We then present SVM-based classifiers

which use two sets of features: N-gram and stylis-

tic features. Our drunk prediction system obtains

a best accuracy of 78.1%. We observe that our

stylistic features add negligible value to N-gram

features. We use our heldout dataset to compare

how our system performs against human annota-

tors. While human annotators achieve an accuracy

of 68.8%, our system reaches reasonably close and

performs with a best accuracy of 64%.

Our analysis of the task and experimental find-

ings make a case for drunk-texting prediction as a

useful and feasible NLP application.

References

Aby. 2014. Aby word processing website, January.

Steven Bird. 2006. Nltk: the natural language toolkit.

In Proceedings of the COLING/ACL on Interactive

presentation sessions, pages 69–72. Association for

Computational Linguistics.

David M Blei, Andrew Y Ng, and Michael I Jordan.

2003. Latent dirichlet allocation. the Journal of ma-

chine Learning research, 3:993–1022.

Josephine A Borrill, Bernard K Rosen, and Angela B

Summerfield. 1987. The influence of alcohol on

judgement of facial expressions of emotion. British

Journal of Medical Psychology.

Angela Bryan, Courtney A Rocheleau, Reuben N Rob-

bins, and Kent E Hutchinson. 2005. Condom use

among high-risk adolescents: testing the influence

of alcohol use on the relationship of cognitive corre-

lates of behavior. Health Psychology, 24(2):133.

Brad J Bushman and Harris M Cooper. 1990. Effects

of alcohol on human aggression: An intergrative re-

search review. Psychological bulletin, 107(3):341.

Christopher Carpenter. 2007. Heavy alcohol use and

crime: Evidence from underage drunk-driving laws.

Journal of Law and Economics, 50(3):539–557.

Chih-Chung Chang and Chih-Jen Lin. 2011. Lib-

svm: a library for support vector machines. ACM

Transactions on Intelligent Systems and Technology

(TIST), 2(3):27.

Ted A Loomis and TC West. 1958. The influence of al-

cohol on automobile driving ability: An experimen-

tal study for the evaluation of certain medicologi-

cal aspects. Quarterly journal of studies on alcohol,

19(1):30–46.

John Merrill, GABRIELLE MILKER, John Owens,

and Allister Vale. 1992. Alcohol and attempted sui-

cide. British journal of addiction, 87(1):83–89.

James W Pennebaker. 1993. Putting stress into words:

Health, linguistic, and therapeutic implications. Be-

haviour research and therapy, 31(6):539–548.

James W Pennebaker. 1997. Writing about emotional

experiences as a therapeutic process. Psychological

science, 8(3):162–166.

Matthew Purver and Stuart Battersby. 2012. Experi-

menting with distant supervision for emotion classi-

fication. In Proceedings of the 13th Conference of

the European Chapter of the Association for Com-

putational Linguistics, pages 482–491. Association

for Computational Linguistics.

Philip Resnik, Anderson Garron, and Rebecca Resnik.

2013. Using topic modeling to improve prediction

of neuroticism and depression. In Proceedings of

the 2013 Conference on Empirical Methods in Nat-

ural, pages 1348–1353. Association for Computa-

tional Linguistics.

Theresa Wilson, Janyce Wiebe, and Paul Hoffmann.

2005. Recognizing contextual polarity in phrase-

level sentiment analysis. In Proceedings of the con-

ference on human language technology and empiri-

cal methods in natural language processing, pages

347–354. Association for Computational Linguis-

tics.